Immersed in the craft processes of Colombian communities, Mario Reina's photographs transport the viewer to feel and relive each stage of the craft process and to get to know the artisans better. In this interview, IMAGO spoke with him about his experiences as a photojournalist in his country.

Mario Reina, a look inside the artisan communities in Colombia

Mario Reina is a jeweler, designer and photographer who has dedicated his career to work with communities and artisans in Colombia. His life story begins in a small town in the south of his country, which at the age of 10 he had to leave due to the armed conflict, moving with his family to Bogota, the capital. This experience and the advice his father gave him one day, “for you to talk about Colombia, you must travel around Colombia”, inspired him to travel around collecting memories and arguments to talk about the place where he was born.

His professional career has focused on vulnerable communities, working with artisans for a state-owned company, travelling to different corners of the country where they live. His bicycle and camera have become his best ally to approach new landscapes, break down social walls and capture the moments and stories of each new culture.

Immersed in the artisanal processes of Colombian communities, through his photography, Marios has managed to transport the viewer to feel the sensations of each of the stages of the process and to get to know the makers in more depth. For this month’s Local Heroes series , IMAGO spoke with him about his travels and experiences with the artisans, and he has managed to immortalize each of these moments how through his camera.

“For me, as a jeweler, designer and photographer, interacting with artisans has given me a greater sensitivity when designing and taking photos.”

Thank you Mario for giving us some of your time. Please tell us about yourself.

My name is Mario Reina. I am an industrial designer by profession, I studied jewelry and specialized in jewelry design. I was born in Neiva, a small city in the south of the country, where I lived for 10 years, making the most of the countryside and its beauty, until the armed conflict knocked on the door of my house and we had to flee to Bogota, the capital. I have a jewelry workshop and a brand that is on pause, due to my current job. I love landscapes, since I was a child I have been obsessed with this, that’s why I try to spend most of the year visiting different places where I can load myself with new mental images and of course photographs.

I could say that this story begins when I was a child and I received the greatest advice my father could give me, which was “for you to talk about Colombia, you must travel around Colombia” a phrase with a lot of sense if we understand the socio-political context of my country. This led me to want to know every corner of Colombia, to be able to talk to the people, see what they see, eat what they eat, go through the hardships that many go through and thus be able to have a more objective argument when talking about my country and its people.

During my career I took an unusual approach for designers and that was to develop products based on the needs of vulnerable communities. This path led me to my current job, in which I hold the position of Creative Director of the National Jewelry Program at Artesanías de Colombia, a state-owned company that supports different artisan communities in the country. My work has taken me to see remote places, their communities and their stories, encountering again the armed conflict and creating a close relationship with the artisans of each region.

Years ago I made the decision to travel by bicycle, as this made it easier for me to encounter unique landscapes, but also helped me to break down the social barriers that in many cases can be created when visiting a different culture. I have already traveled through more than 10 countries and almost all of Colombia.

You are a designer by profession, how did you enter the world of photography?

My love for photography comes from my childhood, when I used to steal my dad’s camera and damage whole rolls of film trying to take pictures. At university I took several photography classes, a bit more focused on product photography, however, my taste for landscapes led me to get a semi-professional camera and escape to take pictures. I was a rock climber and also a mountaineer for many years, which led me to see incredible places. It was at this time that I started taking pictures of what I liked the most.

What does photography mean to you?

For me photography is the way someone can transport you to a specific place. It takes you to imagine how you could feel the wind, the grass, the sun, the sand or the rocks. W hether it is an image of an animal or a person, how it can take you to imagine every sound, feel the smell, the voices, or everything that could be there while capturing the moment. I grew up reading NatGeo magazine and every time I turned a page and looked at the pictures, I felt the way I just described, I was immediately transported, almost to the point of saying “I know that place, because I was there”.

So this is what photography became for me, to achieve through my images, to be able to transport people to the place where I am. The place where they can dialogue with the people who are there, where they can live a bit of how they are living. I t is the way I connect with people and we can enjoy something that we may never know we had in common.

” It is the way I connect with people and we can enjoy something that we may never know we had in common. “

How do people receive your presence when you want to capture photographs in their environment?

It depends on where you are. In Colombia you can find different ethnic groups, indigenous, Afro-Colombian, Raizal, black, Palenquero or mestizo communities. When I work with indigenous communities, the photos are limited, I focus on the context, the landscapes, the objects that I consider to be interesting. But when I want to take portraits, it is more difficult, some people think that the camera is stealing something from them and I respect that. When I want to take full body shots or their faces, not everyone feels comfortable. I think people are intimidated by the lens, so I try to distract them, talk while I take the picture, this makes things easier.However, I like to take full body photos, with their backs to the camera, when they walk, I don’t need their face, their body walking is telling me about the passage of people on earth, about their day.

When I was in Bolivia, the indigenous people were very reserved with photos, however, when they saw me arrive by bicycle, the conversation revolved around the distance traveled and the difficulty of the journey, this allowed me to create a link and thus take photos of the context. I found it fascinating to see how people walked small trails at more than 4000 meters above sea level, carrying wood, grains, fabrics, to see shepherds accompanied by llamas, sheep and their children… It was incredible to see the silhouette of each one in the middle of that vast Andean landscape.

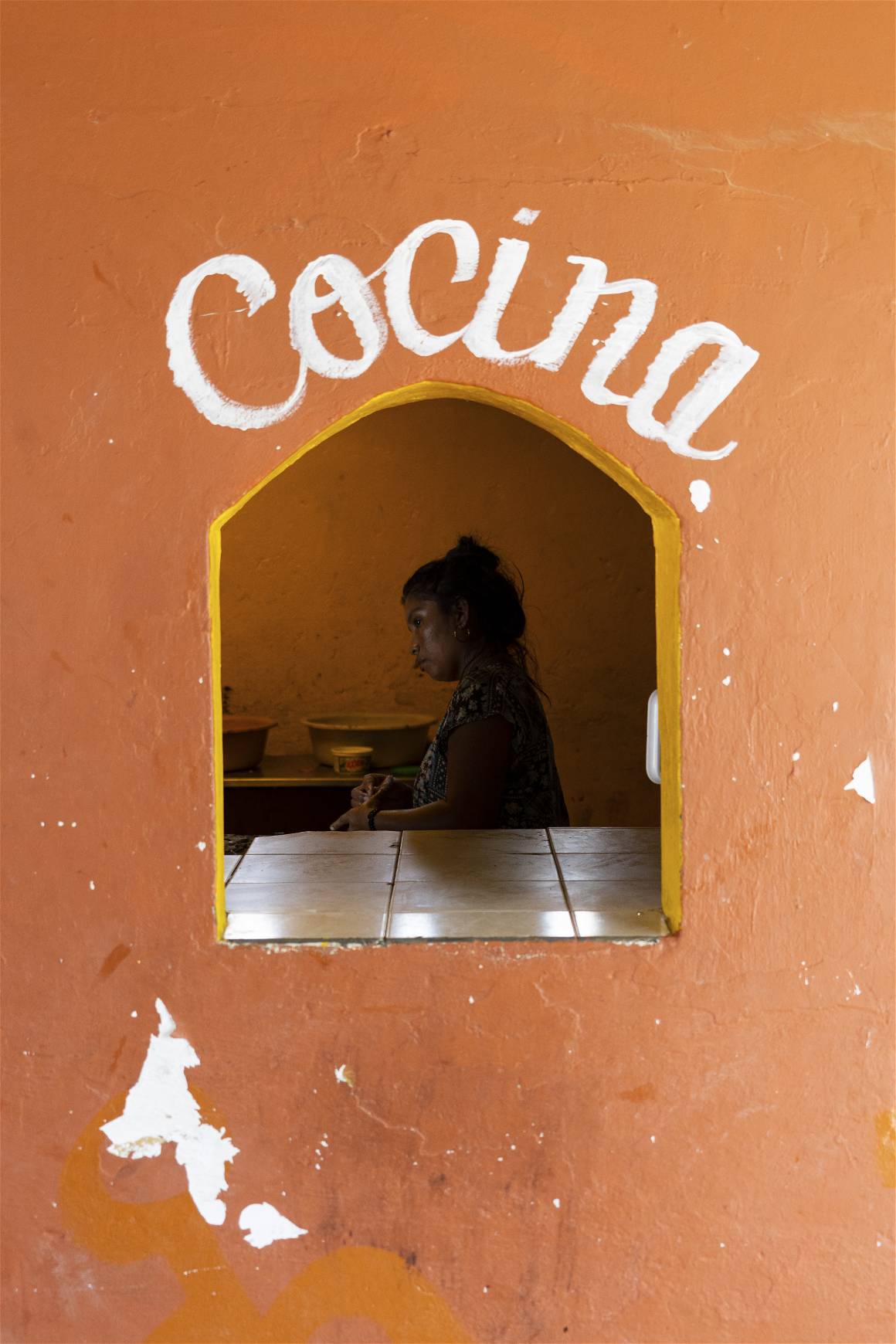

When I take pictures while they are doing a specific activity, as in the case of artisan crafts, I can find two types of people, those who follow their activity in a natural way and those who are willing to model. T hey make small pauses so that the picture comes out much better, but never looking at the camera. The crafts are wonderful in every way, because you have to understand the process very well before taking a picture, so you know how to make the most of every detail.

Otherwise, people enjoy the photos, they always ask me to give them their photos, so I usually send them the images I have taken.

“When I want to take portraits, it is more difficult, becuase some people think that the camera is stealing something from them. “

Your photos show the daily life of people in rural areas, and their daily activities. What is your main motive and intention behind your work?

Colombia is a diverse country, its ethnic multiplicity is accompanied by a large number of handicrafts, used in the daily life of a community. Whether as utilitarian elements that allow them to carry food, store liquids or cook, or as pieces with symbols or shapes whose use is related to religious beliefs. This is how handicrafts become representative objects of the different regions of the country and their crafts become the legacy that keeps alive the traditions of each people. My main driving force is to be able to understand each craft from the beginning. Starting with the procurement of the raw materials to the final sale of the product.

For many, a basket, a hat, a múcura, a thinking bench, a piece of jewelry or animals carved in wood, can be summed up as an object that is the result of a manual process. Whose work takes several hours or days, where the master uses his or her experience to create complex figures from unique techniques. For me, handcraft is an object whose socio-cultural charge is detached from simple use, creating a dynamic fabric between different individuals of a community.

When an artisan from the Kubeo community, in the Vaupes, makes a piece of pottery, his activity is not limited to transforming the clay, molding it into the desired shape, waiting for the piece to dry and then firing it in the kiln to obtain the vessel. This begins with the search for the clay in the interior of the Amazon jungle, where after a protection ceremony, the artisan receives permission from mother earth to extract the precious blue colored clay. After crossing the jungle and paddling down the river, the artisan returns to his workshop, where he must fetch the wood that allows them to smoke and burn the ceramic pieces.

Different actors are involved in this process, the people who accompany the artisan to find the mud, who allow him to cross the river, with whom he will probably fish for breakfast and lunch, sharing stories as they make their way. Then, to fetch the wood he must go into the jungle; for safety he will be accompanied. Along the way, they will be able to talk about the different types of wood, the specific uses and medical benefits of many plants found there. They will select leaves and small fruits to make the natural dyes applied to the ceramics.

Then the workshop is ready, here comes the specific part of the artisan’s work, where the master will use all his skill and experience to make a pot or vase. The artisan makes pieces to order, whose purpose can be functional or simply to exchange for food or other handicrafts. Once the making and burning process is finished, the artisan takes his or her products to the local market, where different indigenous communities gather to sell and buy food. This last step allows the artisan to interact with other masters about their work and knowledge, generating an exchange of knowledge and techniques.

My intention is to capture every moment, so people can see what revolves around an artisan activity and the importance of this for their communities. So they can appreciate every detail of the work and the added value that the object developed by each community. This can have a positive impact for the artisans, their product become more attractive to people, generating more sales and and gaining visibility in the national market, the process makes people fall in love with it. On the other hand, customers can get objects of which they know the history, they know how the idea was born and how it materializes generating a deeper connection with the object.

” My intention is to capture every moment, so people can see what revolves around an artisan activity and the importance of this for their communities . “

What have you learned so far from immersing yourself in the artisans’ environment?

My experience with the different artisan communities in the country has allowed me to understand in depth the reality of Colombia. B e able to see the conditions in which many people have to struggle to get ahead with their families; to understand the armed conflict and its dynamics. But above all, how the crafts manage to form a methodical and disciplined spirit in each person who decides to practice it.

Each trade requires a suitable environment to be able to practice it, the tools are not the same nor the raw materials; however, the structure of the trades is similar. Specific steps must be followed to reach the final object. Beyond the traditions, the ancestral knowledge, the cultural value of handmade objects, craftsmanship can teach many things to each person, either as a lifestyle, changing habits that allow them to focus more on the work.

For me, as a jeweler, designer and photographer, interacting with artisans has given me a greater sensitivity when designing and taking photos. Understanding the processes allows me to know the right moment when I should shoot the camera, always looking for images that can communicate to the maximum the activity that the person is doing, that is, that the viewer manages to feel the moment and in some cases imagine how the textures of the material are.

Do you have a special project that has had a resounding impact on you? Can you tell us a bit about that experience?

Yes, it was on a visit to the community of Barbacoas in Nariño. I accompanied the women “barequeras” (traditional miners) to look for gold in an old stream that for years was the meeting place for different women miners. When they described the place to me, they told me about the creek and the small waterfalls that formed there, the plants around and the different animals that could be seen. After two hours by boat on the Telembí river, we went through a small stream until we reached a wooden hut, around which there were several coca fields; this made me think that I was in a complicated place.

There we picked up some shovels and several bateas, a wide wooden plate with which they clean the land to look for the small gold flakes. We walked for several minutes and sudenly, the vast jungle was replaced by a wasteland with several holes and water wells. I looked at one of the women, she told me in a low voice “it can’t be, the dredgers have arrived”. I realized that we were in an illegal mine, where the women used to sit with their little ones to clean the land and look for gold, had become a huge deforested field, with several machines making holes and depositing the earth in a huge tower; the creek had dried up and fed the tower where liters of water cleaned the land.

We stopped quickly when three armed men approached ust. The women told them that they were coming to look for gold and that I was accompanying them to take some pictures of the process; in a curt manner they replied “it’s not here, you must walk for another hour and find a place where you can do it”. I approached the three men and explained the situation, I asked them if we could do the activity there, in one of the wells, as we did not have much time; one of the men called another one and they gave us permission.

They told me, “you can only take photos of the well, you can’t leave anything else, as this is an illegal mine and the army is after us”. I very cautiously positioned myself at an angle where all the photos I would take would focus on one of the women and thus avoid any inconvenience. I took 3 photos.

Then when we left, I understood that we were in an illegal mine of the armed groups of the area. They look for the places where the traditional miners extracted gold, to then exploit the area to the maximum with heavy machinery. Of that place that the women remembered fondly and wanted to share with me, only mud remained.

For you, how do you know when the ideal moment to capture a photograph is?

I think a lot of photographers agree on this and it becomes instinctive. I don’t look for the moment, I wait for it to come. By this I mean that I may want to take pictures of something specific, but I sit and wait. I really like to observe people and their context. I take time to see everything and decide at what moment to use the camera. In my head I always think “at any moment I can see something that deserves a photograph” and unintentionally, this habit saved my camera on a certain occasion, when the river overflowed and flooded the town, the water entered my room and wet my suitcase , my computer, my clothes.

With landscapes it’s different, they are the greatest pleasure I can experience. When I see a place that captivates me, I sit down and wait for hours, just enjoying it, then I take the picture.

“I don’t look for the moment, I wait for it to come . “

What recommendations would you give photographers to capture the spontaneity of the moment?

I think the key is to break the barrier between the camera and the people. My advice is to get to know the people, situations and places you want to capture as much as possible. When working with artisans or ethnic communities, it is important to establish a dialogue, to create a bond of friendship that allows them to act in a natural way; that they don’t feel the pressure of the camera, but that a friend is with them and will take photos from time to time. Once you manage to establish this bond, capturing an image is easier, the smiles in the portraits, the movements, the faces, even the posture when they are there, can change a lot.

“My advice is to get to know the people, situations and places you want to capture as much as possible.“

Other previous articles on marginalized groups include:

What is left of Yemen’s Jewish Community

Black History Month: The fight for voting rights in the United States

How LGBTQ+ Community’s largest demographic falls between the cracks.