Capturing the many faces of a crisis is not only a delicate craft, but creates an archive of current issues. “This movement is part of our contemporary history and must be registered,” said Brazilian photojournalist Chico Ferreira from Penta Press. IMAGO spoke to Ferreira about his work depicting the reality in Brazil at its core, from politics to the pandemic.

Brazil’s Heroes: An interview with Chico Ferreira.

A growing political divide, a country shaken by the pandemic and a glimmer of hope. In Brazil, the upcoming elections and the staggering vaccination rate are bringing change to what was a turbulent past year. Former President, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, is for some Brazilians the saving grace in the 2022 elections – for others, he’s Brazil’s greatest nightmare. Brazil’s current political polarization both among the population and within the electorate has not only brought massive social upheaval, but has played a major role in the country’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.

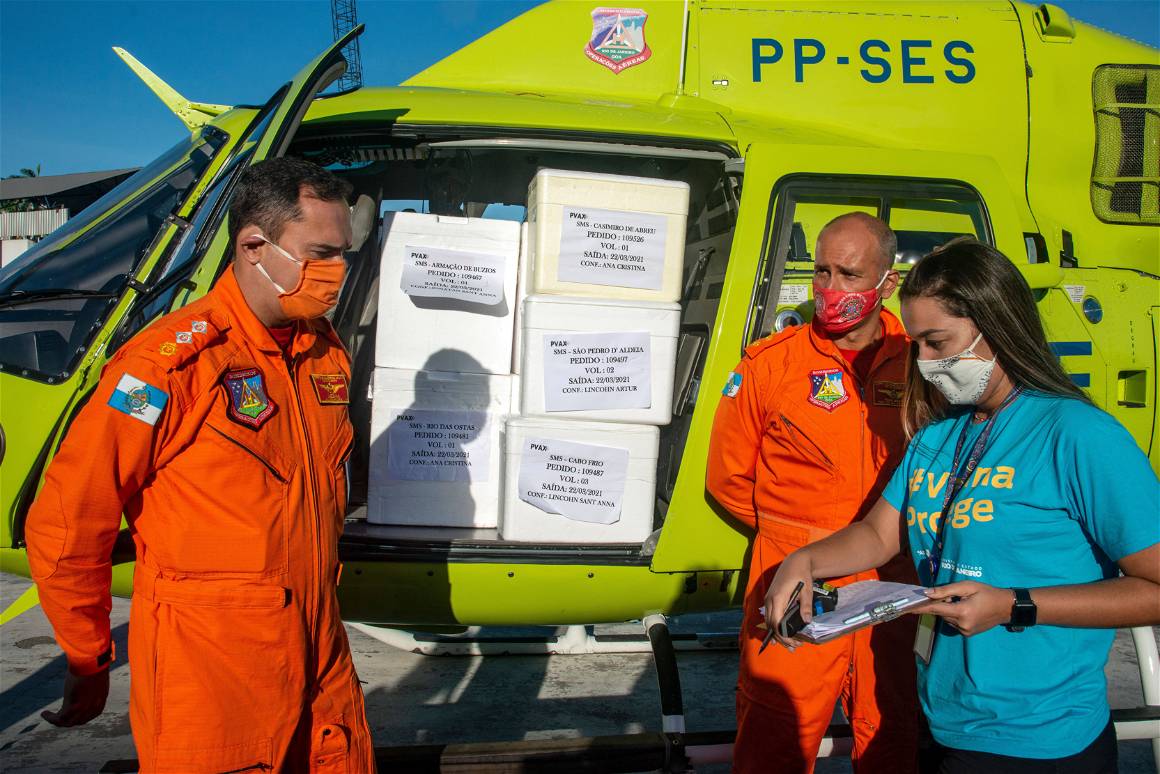

Founder of the Leftist Workers Party (PT), Lula da Silva’s corruption charges from 2017 were recently annulled by the Supreme Court, allowing him to run for president again, and where he now faces right-wing incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro. A cocktail of alleged misinformation, Bolsonaro might even face charges for his efforts in blocking local leaders from taking action and a general denial of the virus’ severity. His neglect has invited criticism internationally and has even brought opponents to write “Genocide” on their signs at protests. In fact, over 600,000 people have died in Brazil since the beginning of the pandemic, making it one of the worst-hit countries worldwide. Now with over 70 percent fully vaccinated, coupled with plummeting cases and immense efforts to raise awareness and solidarity, Brazil has started to see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Ferreira has witnessed and documented NGO efforts, scientists and activists who have come out as some of Brazil’s greatest heroes. Showing those both taking action and maneuvering daily life in Rio, from the favelas to Copacabana beach, he offers a perspective on Brazil’s battle through the pandemic and its immense socio-political divide.

A lot of your work focuses on efforts from NGOs like Rio de Paz raising awareness of Covid-19 and helping communities. What brought you to document these initiatives?

The political situation in the country has deteriorated drastically in recent years and this has been reflected in dealing with the pandemic, with hundreds of thousands of deaths, many of which could have been avoided. Any form of protest that helps people to understand what is happening is valid and the work of NGO Rio da Paz has the strength to convey this message

What is the general sentiment among volunteers and activists? Were there any moments that stood out to you?

The feeling has always been the same throughout the coverage of the pandemic, sadness. Even during actions that brought joy and solidarity, such as the donation of food, the feeling that this tragedy, if not avoided, could have been minimized with political decisions based on science and not on denial, was a constant.

The most striking situation was that of a passerby who was not part of the “action” of placing crosses in the sand on Copacabana beach in protest for the more than 40,000 deaths at the time in the country. The symbolic crosses were torn off by a supporter of President Bolsonaro. In the wake of the confusion that took place, with tears in his eyes, a man who was passing by on the beach said that his son was one of the victims, and he restarted placing the crosses in a solitary act.

Brazil was hit very hard with the Covid-19 pandemic but the situation has been improving thanks to vaccines. I am curious about the discourse among locals in Brazil surrounding Covid; How has it affected you?

The political polarization between left and right has extended to all areas, environment, culture, science and even to the area of health. Decisions that should have been technical started to be taken according to an ideological bias and that was a disaster.

Even with the numbers showing mathematically that vaccination, although it does not prevent the contamination, has a disastrous reduction in the serious cases and deaths caused by Covid-19, an aura of mistrust was created. Unfortunately, this doesn’t only happen in Brazil, and today we are witnessing anti-vax movements spreading across the planet.

In Brazil we have always had a model culture in vaccination campaigns and today we have a percentage of the population fully vaccinated that is higher than countries in North America and Europe with much more economic resources. This proves that if we had had an information campaign and practical actions by the government from the beginning, the impact of the pandemic would have been much smaller.

As a photojournalist, you are able to understand the current climate surrounding you. You have also photographed pro- and antigovernmental protests, vaccination campaigns, and daily life. What is important for you to show in your photography?

As a citizen I have my ideology, my beliefs and my preferences, but as a journalist I have to keep a commitment to the facts.

Although the ‘message’ transmitted always has a personal ideological charge, it is the journalist’s job to document the facts, and this must be done always seeking the maximum possible exemption.

Even with all the disapproval I have for the current government’s supporters, this movement is part of our contemporary history and must be registered.

The current political situation in Brazil is very polarized, but elections are coming up next year. Can you please tell me more about this, and what you think will happen during the elections?

Since the impeachment of former president Dilma, forged with political and legal maneuvers, the country has been divided.

The high levels of corruption in all political and economic spheres created a favorable field for the emergence of extremists with hate speech and false promises of changes that ended up electing the current government. But the administrative incapacity, together with the impact of the pandemic, generated inflation, unemployment and crisis, especially in the poorest layers of the population, as had not been seen for a long time. And this will all be reflected in the upcoming elections. The biggest doubt is whether the dispute will remain in the republican and legal molds, or whether democratic institutions will not collapse in the face of violent and radical acts.

Chico Ferreira was born in Rio de Janeiro, where he is now a freelance photojournalist capturing the shape of the city, the lives of it’s people and the everchanging politics.

Article and image selections by Sofia Bergmann.