It is a unique trick to make a photograph of the most prestigious trophies in club football – four Champions League cups, 10 La Liga crowns, seven Copa del Reys and more – project an aura of humiliating failure. But that is what Barcelona managed when they shared an image on social media, showing the full collection of Lionel Messi’s achievements, after the club’s greatest ever player was clumsily shoved out the door.

The rise and sudden fall of the power of Spanish club football by Alex Reid.

Featured & written for IMAGO Zine #3 | La Liga. Get your copy and subscribe to our zine series here.

The photo was designed to create the illusion that Messi’s departure was some kind of joyous farewell; a glorious era coming to a happy ending. Instead it just looked like the end.

FC Barcelona, one of the two or three biggest clubs in the world, had let their best player, the footballer they wanted to keep above all others, walk away for nothing, so that they could keep paying a group of players they do not want. And this after Messi had agreed to a 50 percent pay cut. How can any football club run up a €1.35 billion debt before their own league has to step in? As the joke goes: “mess que un club”. Except nobody at Camp Nou is laughing.

It is an achievement, of sorts, when you eclipse even Real Madrid (a reported €901 million in debt) in reckless spending. Yet Los Blancos suffered their own humbling summer: after their club legend coach Zinedine Zidane departed (again), their talisman Sergio Ramos also left. Ramos is 35 and injury-prone of late. But still: that is the captain of Barcelona and the captain of Real Madrid, both walking away to join Paris Saint-Germain, for free, in the same transfer window.

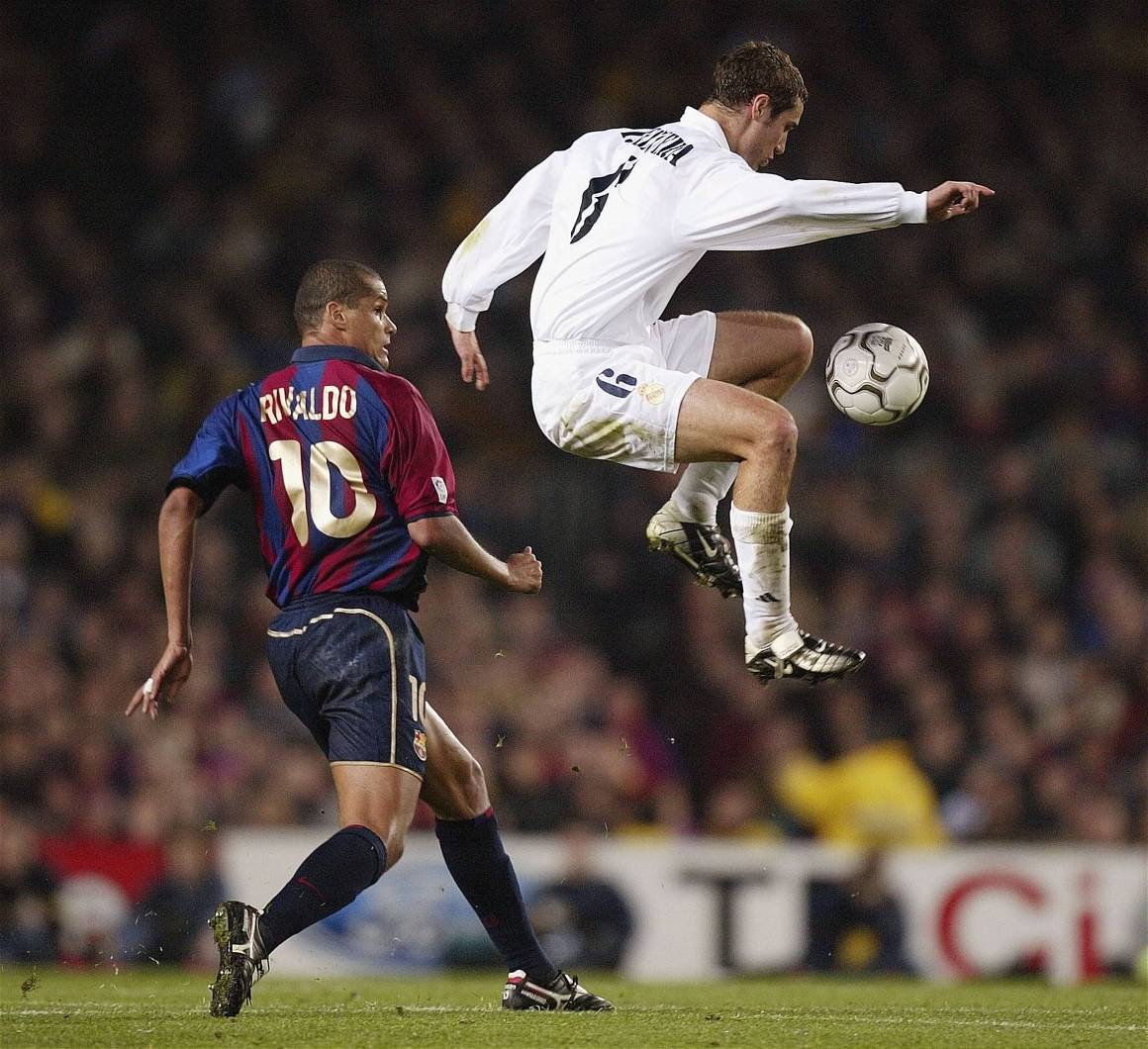

The symbolism is not lost. For a decade, watching felt like watching the two greatest football clubs on the planet battle it out each year in a deeply personal grudge match; football’s version of Ali vs Frazier for a new generation. Between seasons 2008-09 and 2017-18, Barcelona and Real won seven of 10 Champions League titles between them.

For those who sneered that La Liga was merely a two-team league, the evidence to the contrary is clear. Atlético Madrid were the losing side in two of those finals. And the Europa League, a fair indication of which league boasts the best teams outside their top two or three clubs, saw La Liga even more dominant: 10 of the winners in the last 16 seasons have been Spanish clubs.

La Liga has had, broadly, the best teams and next-best teams – and the brightest stars. If the whereabouts of the greatest player in the world is an indication of which European league is the strongest, and it is a good rule of thumb, La Liga has had the upper hand for 20 years.

In the 1980s and ‘90s the honour belonged to Serie A. Diego Maradona at Napoli, followed by Marco van Basten and his brilliant Dutch colleagues at AC Milan, then Ronaldo at Inter Milan (taken from Barcelona, no less) and Italy’s own homegrown genius Roberto Baggio at Juventus. But gradually, towards the end of the 20th century, the balance of power tilted towards Spain – and Real Madrid in particular. Perhaps it was the move of Zidane from Juventus to Real in 2001, for a then world-record fee of €77.5 million, that stamped the change. A new century had begun and a new league was set to dominate.

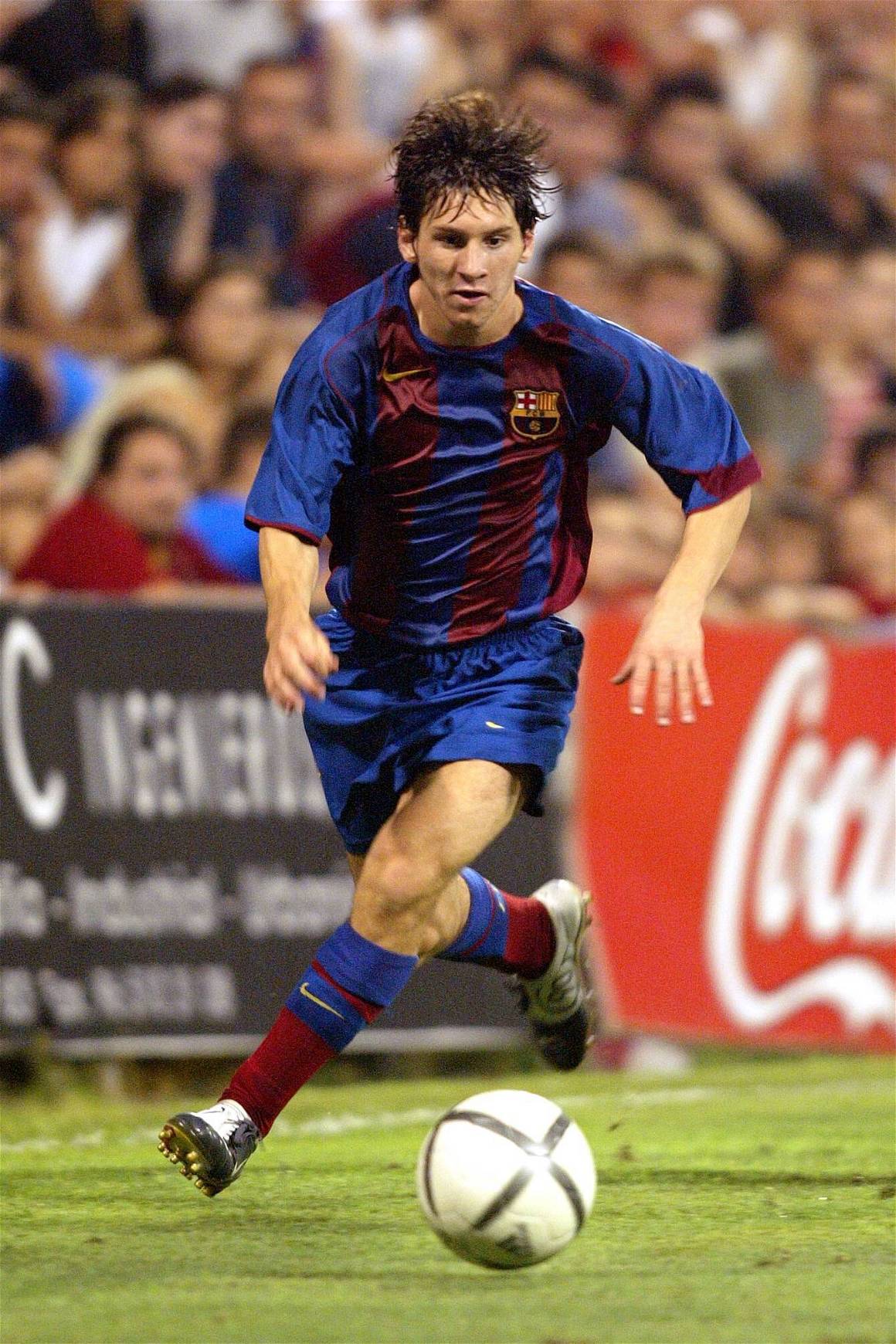

Real bought their Galacticos, swiping the best players from clubs of the stature of Liverpool (Michael Owen), AC Milan (Kaka) and Manchester United (Cristiano Ronaldo). Barcelona developed many of theirs, a special generation came through La Masia – Xavi, Andres Iniesta and Messi the crown jewels – coached to fruition by a club legend in Pep Guardiola.

Now Xavi coaches in Qatar, Iniesta plays in Japan, Messi in Paris, while Guardiola manages in England. Instead of promoting youth players to replace the ones that left, Barcelona turned into their own worst enemy – a buying club; an ersatz Real Madrid. For a short while it worked, supercharging their attack with Luis Suarez and Neymar to complement Messi.

As a Barcelona side with that attacking trio faced off against a Real team with Ronaldo, Gareth Bale and Karim Benzema, it felt as though the world’s best players were crammed into two club sides. It was the loss of Neymar for an extraordinary €222 million fee that seemed to break Barcelona. A battering-ram message from Qatar-owned PSG that the Barca-Real axis couldn’t bully other clubs with their financial muscle any more.

Barcelona did not read the warning. Instead they spent that exorbitant transfer fee, and more, on a series of jaw-droppingly wretched deals. Philippe Coutinho for €160 million, Ousmane Dembele for €105 million (plus add-ons), Antoine Griezmann for €120 million – all with the wages to match. Numerous other players arrived, none of whom seemed to actually strengthen a Barcelona XI still relying on Messi on Gerard Pique on Sergio Busquets on Jordi Alba. On the players who were already there, in fact. It culminated in the tragicomedy of their record signing, Coutinho, being loaned to Bayern Munich and scoring twice against Barcelona to seal an 8-2 Champions League humiliation last year.

Away from Barcelona’s own personal hell, there is a bleaker message. That even without the Catalan club’s grotesque wastefulness, the writing was still on the wall. The marketability of Barcelona and Real Madrid will always attract players, but the pandemic has shone a light on a cruel fact: without fans in stadiums, the size of those mighty global Premier League TV contracts become even more important.

The growth in the value of Premier League TV rights is startling. Between 2010 and 2013, they were worth around £1.8 billion worldwide. From the three-year cycle of 2019 to 2022, the income will be an estimated £9.2 billion. Belatedly, La Liga began selling their global TV rights collectively in 2016-17 rather than letting clubs strike their own deals, but they are still playing catch-up.

The straits La Liga finds itself in have meant a firesale to raise urgent funds. A Liga plan to sell 10 percent of the competition, for €2.7 billion to private equity firm CVC Capital Partners, was labelled “appalling” by the Spanish Football Federation. But clearly Spanish clubs need money. Even Real Madrid cannot just sell their training ground to the government to cover their losses (it is not 1996, after all).

And even Atlético Madrid, supposed outsiders in Spain’s big three, owe a reported €290 million yet chose to spend €126 million on unproven Joao Felix two years ago. The pandemic may have exacerbated all of the problems these clubs face. But this crash was coming.

A silver lining, however, does exist. In a European football scene where the Premier League elite are only growing stronger, where PSG operate without apparent constraint, where Bayern Munich and the top German clubs are better set up to survive financial hardship, Spanish clubs have something in favour beyond just reputation: the sheer depth of their talent resource.

There may have been an inevitable lull after Spain became the first European nation to win three major international tournaments between 2008 and 2012, but it was far from a terminal decline. One look at the gifted Spanish squad that competed at this summer’s belated Euros – and the young players who did not even make that – tells you that Spain boasts a precious resource of talent.

Pedri, Oscar Mingueza and Ansu Fati of Barcelona. Mikel Oyarzabal and Martin Zubimendi of Real Sociedad. Pau Torres of Villarreal. The issue of course is that other clubs in other countries will try to snatch these players (Ferran Torres is already at Manchester City; Dani Olmo at RB Leipzig). But Spanish clubs can get to these players first.

In fact, to give them credit for foresight, Real Madrid have been trying this for some time and there was a hope several years ago that the likes of Isco and Marco Asensio could become semi-homegrown Galacticos. That plan has not quite worked but the method is correct.

Even if La Liga’s largest clubs can no longer afford to buy the biggest names, it does not mean the future is barren – particularly as recent evidence suggests they were spectacularly bad at doing that anyway.

Technically brilliant young footballers. Sharp coaching brains. Passionate fan-bases returning to stadiums. These are things La Liga can build on, even if its era as the financial superpower of Europe – an inevitable magnet for the greatest superstars – is almost certainly at an end.

Alex Reid is a sports writer and columnist for The Game. This article is featured and written for the IMAGO Zine #3 | La Liga. Get your copy and subscribe to future issues.