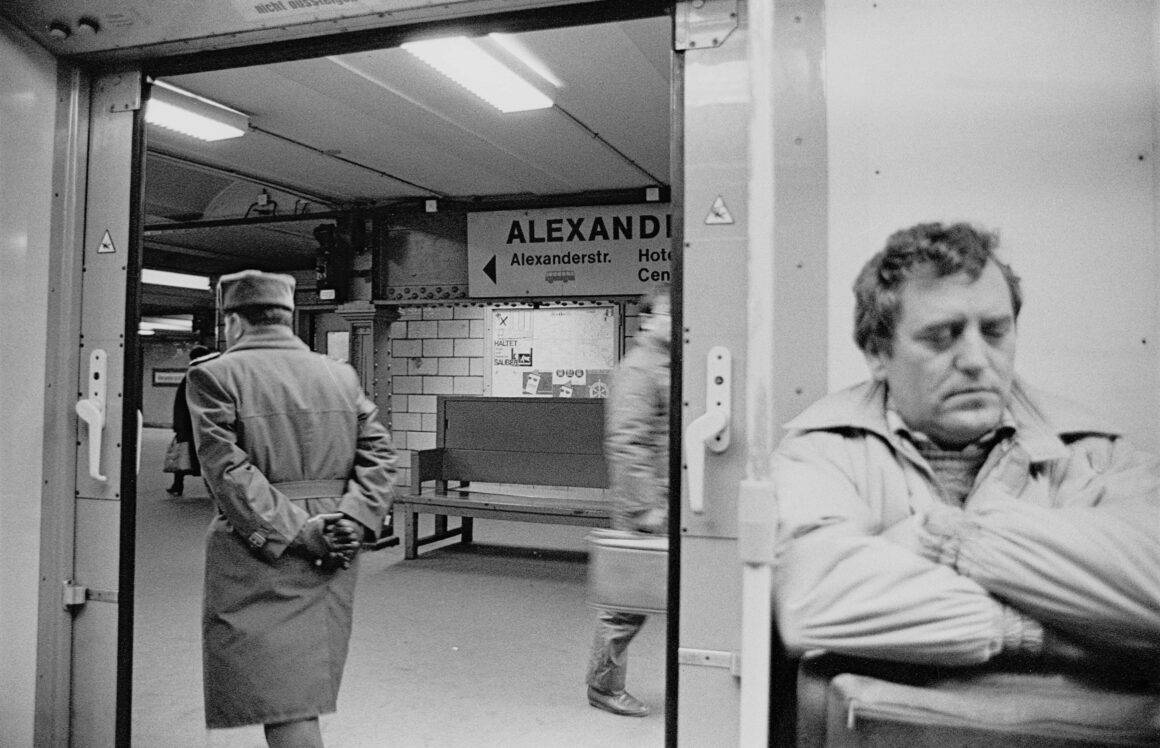

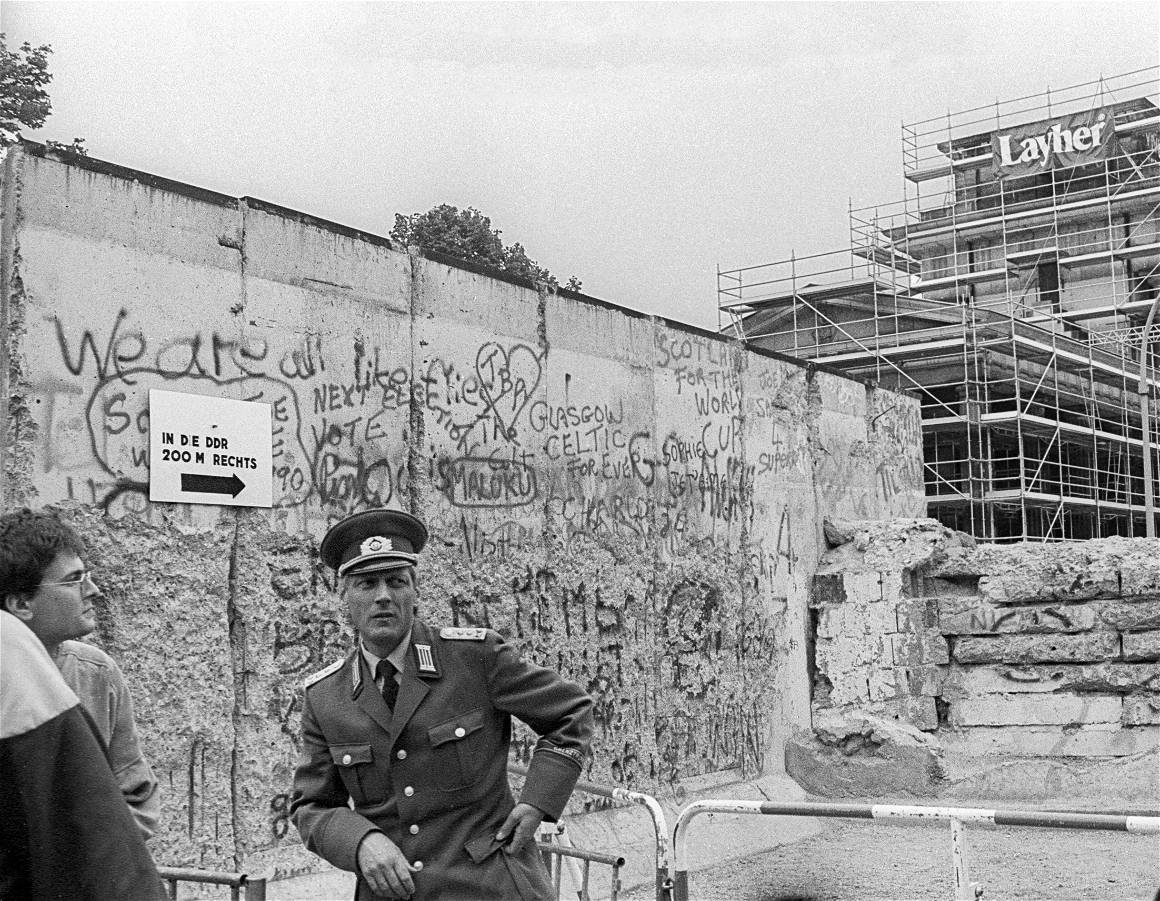

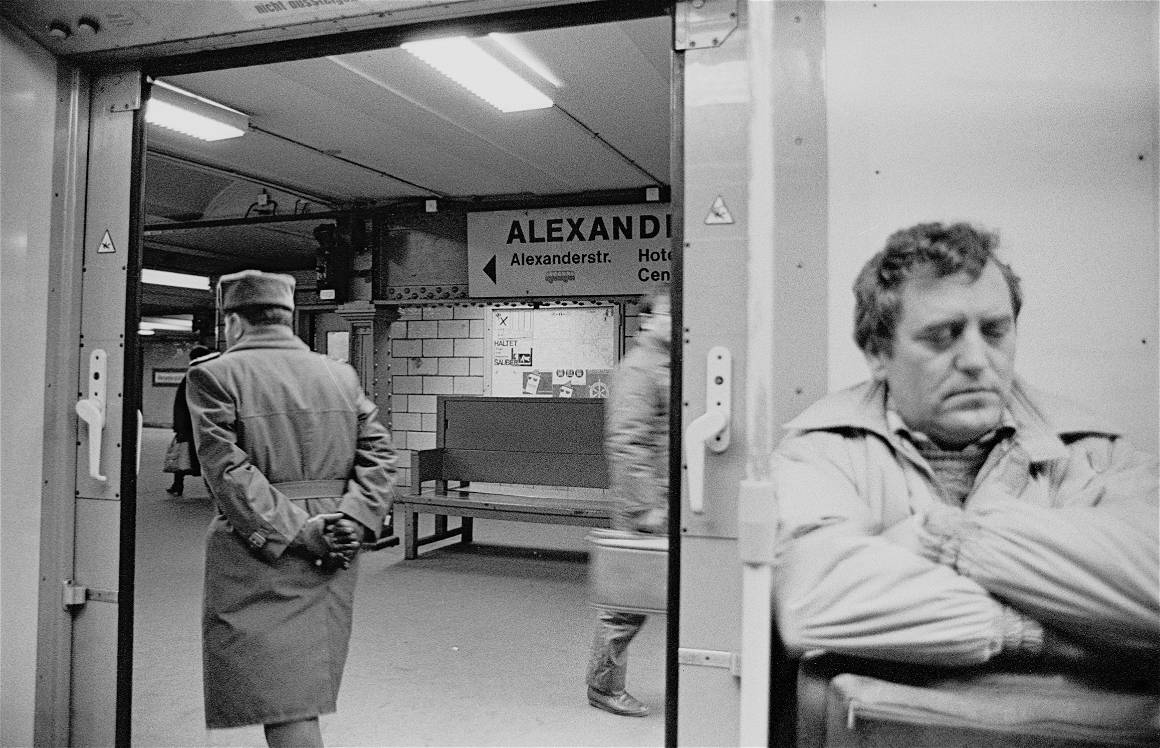

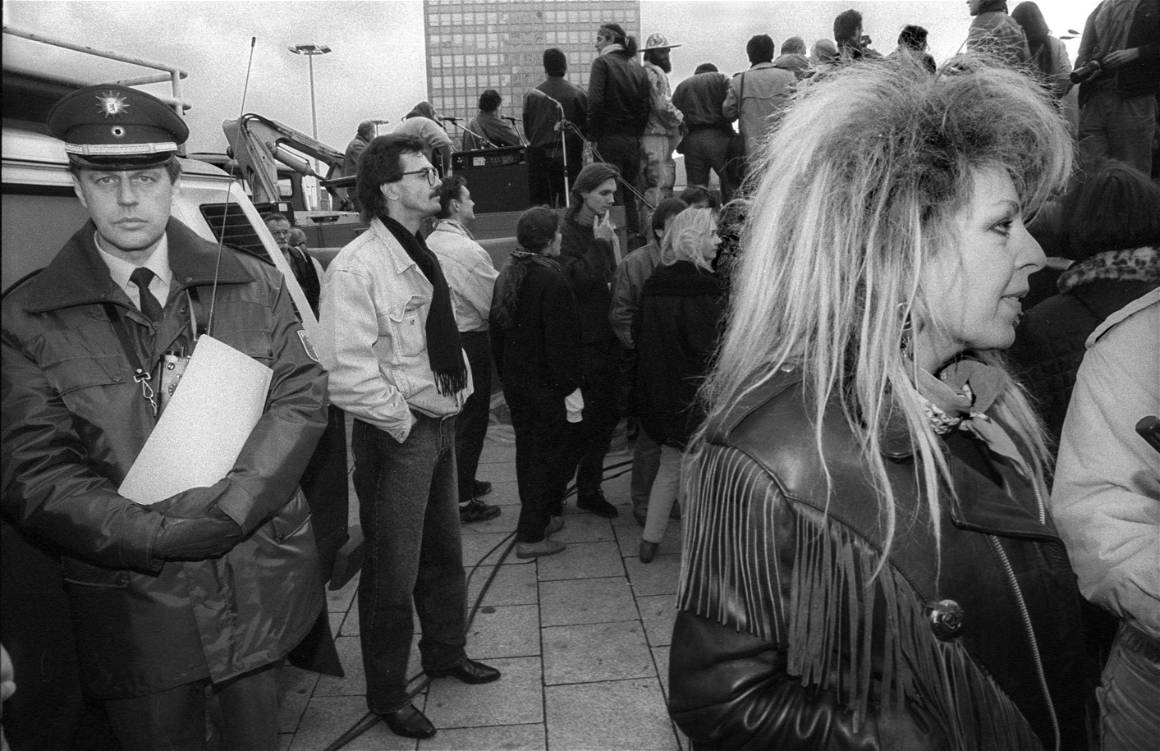

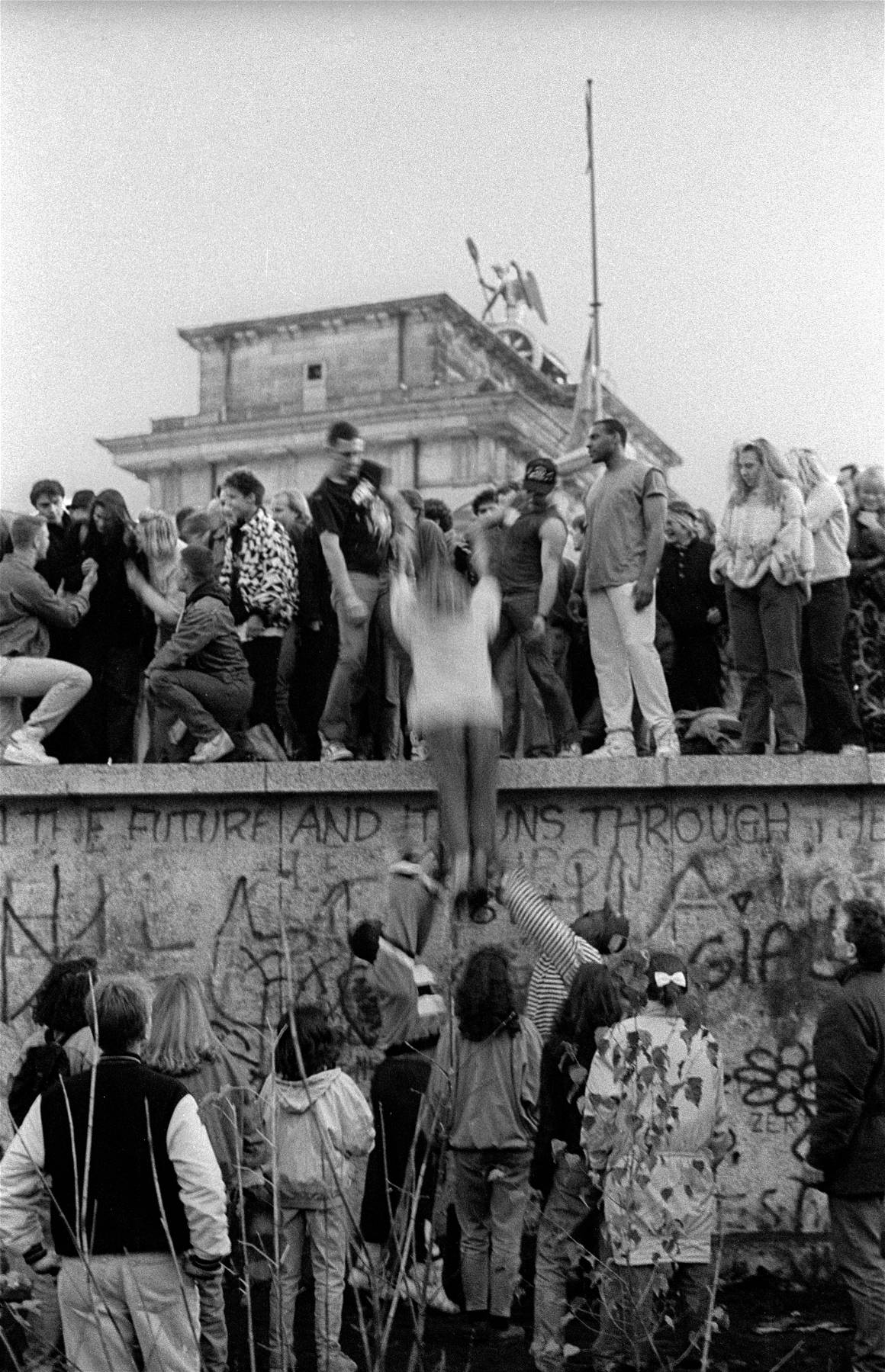

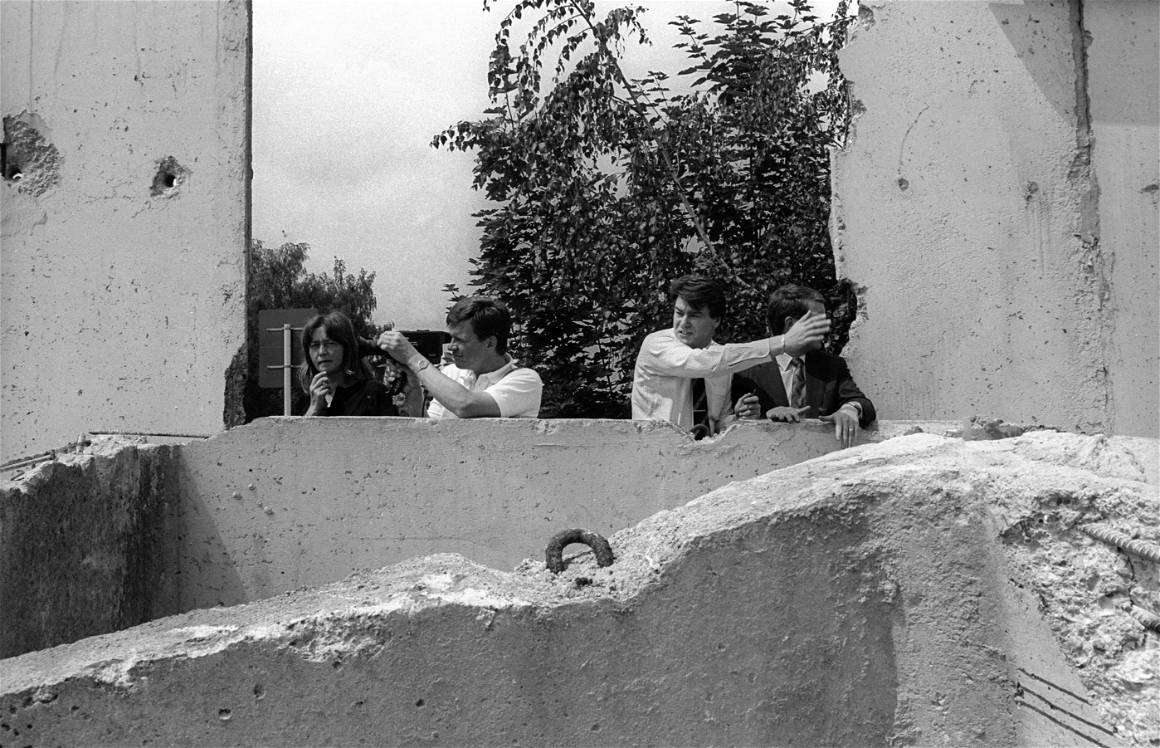

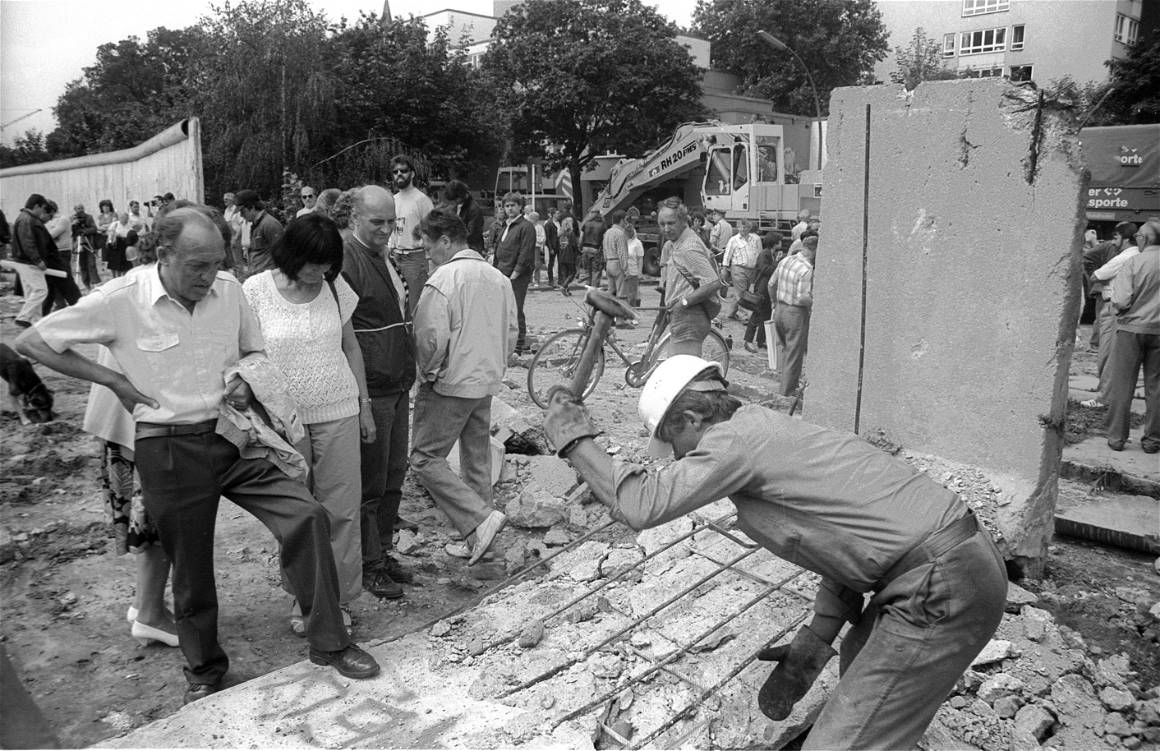

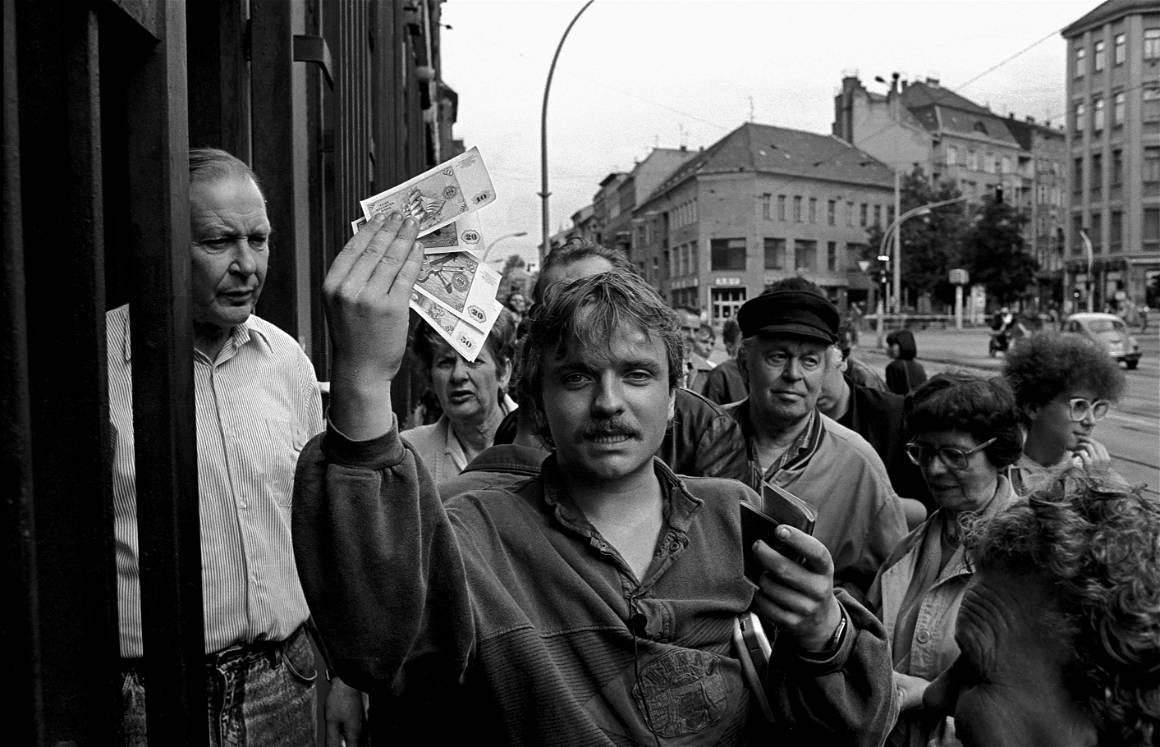

East Berliner and photographer, Rolf Zöllner showcases his stunning black and white film photography in an interview covering life in Berlin during the height of its culture. Experience the fall of the wall through his lens and immerse in the iconic movement and moment of the unification of our ace city.

Fall of the Berlin Wall: An Interview with Rolf Zöllner.

Featured and written for the IMAGO Zine #2 | ICONS. Get your copy and subscribe to our upcoming issues.

When and how did you start photography? What drew you to working in the medium rather than anything else?

It actually began in the youth club of our village (Lichtenau), my girlfriend at the time, who was training to be a photographer, founded a photo circle when I was about 19 years old. Interest soon waned, only holiday photos etc. were developed in the darkroom anyway – nothing serious. Later, in my darkened children’s room, I developed at least a few photos from the village. But a more serious occupation began only after I moved to Berlin in 1978.

First in the Spandauer Vorstadt, where I lived, later also in Prenzlauer Berg after founding the photo circle (photo club) of the Kreiskulturhaus Prater. The circle leaders Roland Hensel and, after his departure to the “West”, Jürgen Nagel taught me the craft. In 1978 I realised that my previous profession as an electronics technician could not be the fulfilment for me and I jumped into the “cold water” and quit. After that I worked as a freelance film photographer (still photographer) for GDR television and learned a lot about dealing with actors, celebrities, film crews and people themselves. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, I made the leap into photojournalism. My clients were TAZ, Wochenpost, Spiegel, Die Zeit and many others.

How did you end up living in Berlin? And why did you choose to stay?

In 1978 I worked as an electrician on large construction sites in the GDR. On this occasion I met a woman in Berlin and stayed.

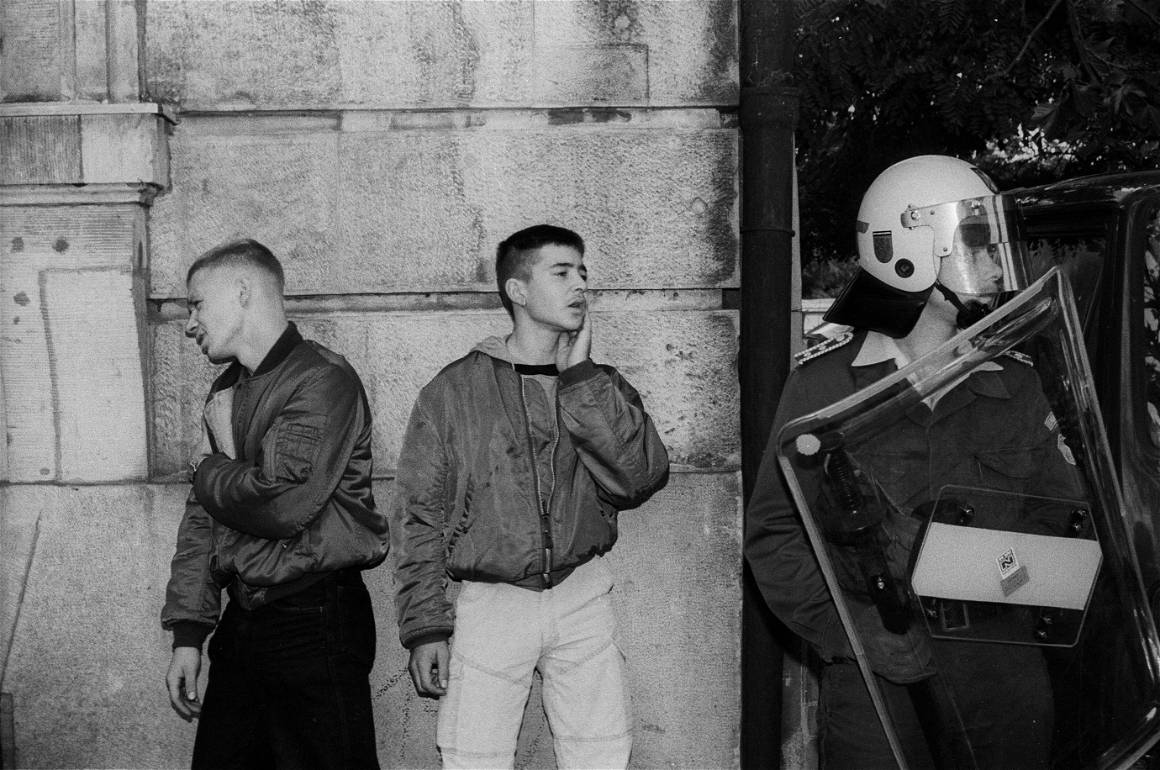

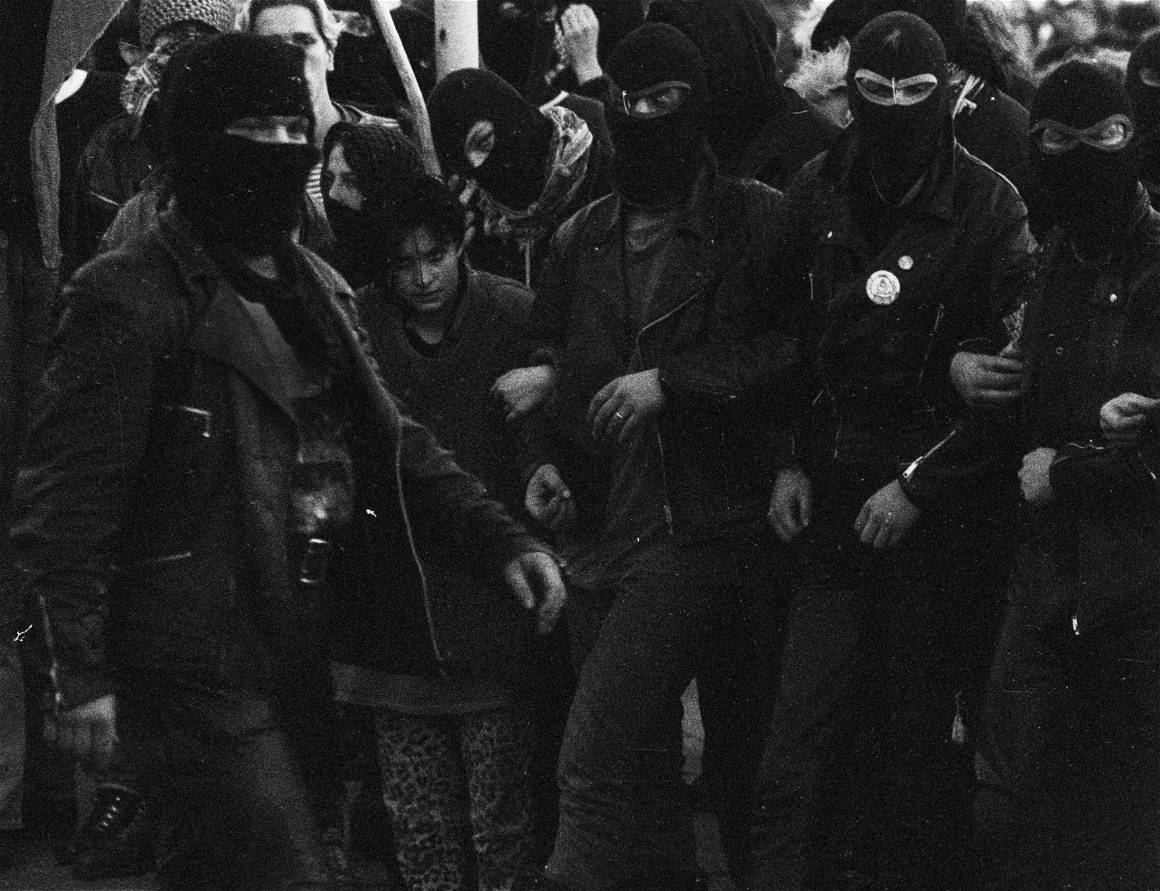

Can you describe to us what the city of Berlin looked like in the 80s and 90s. What was the culture like? How was it to be a Berliner back then?

As an East Berliner, I can of course only tell you about that part. As far as culture was concerned, East Berlin had a wide range of things to offer. Two visits to the cinema and theatre per week were not uncommon – they cost almost nothing: the first row of the State Opera cost 8.15 GDR marks. There were legendary productions at the Deutsches Theater. My first exhibitions were devoted to jazz music. In the 90s, I was particularly interested in the culture of the years of change – it took place right in my neighbourhood at the time, the Spandauer Vorstadt. The first trendy pubs – cafés, the emergence of the Auguststraße art mile, squatted houses, etc.

You have a great archive of black and white film photography of Berlin spanning many years. What are your most memorable experiences or impressions from that time? Did you photograph them?

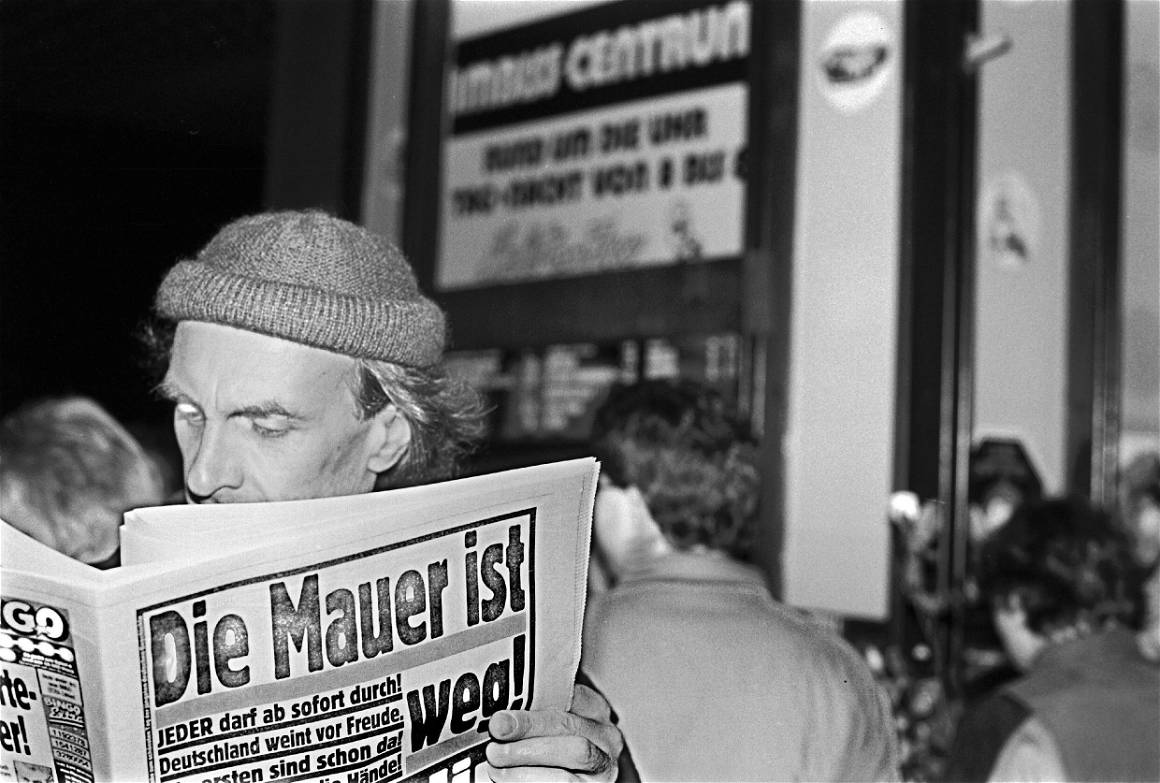

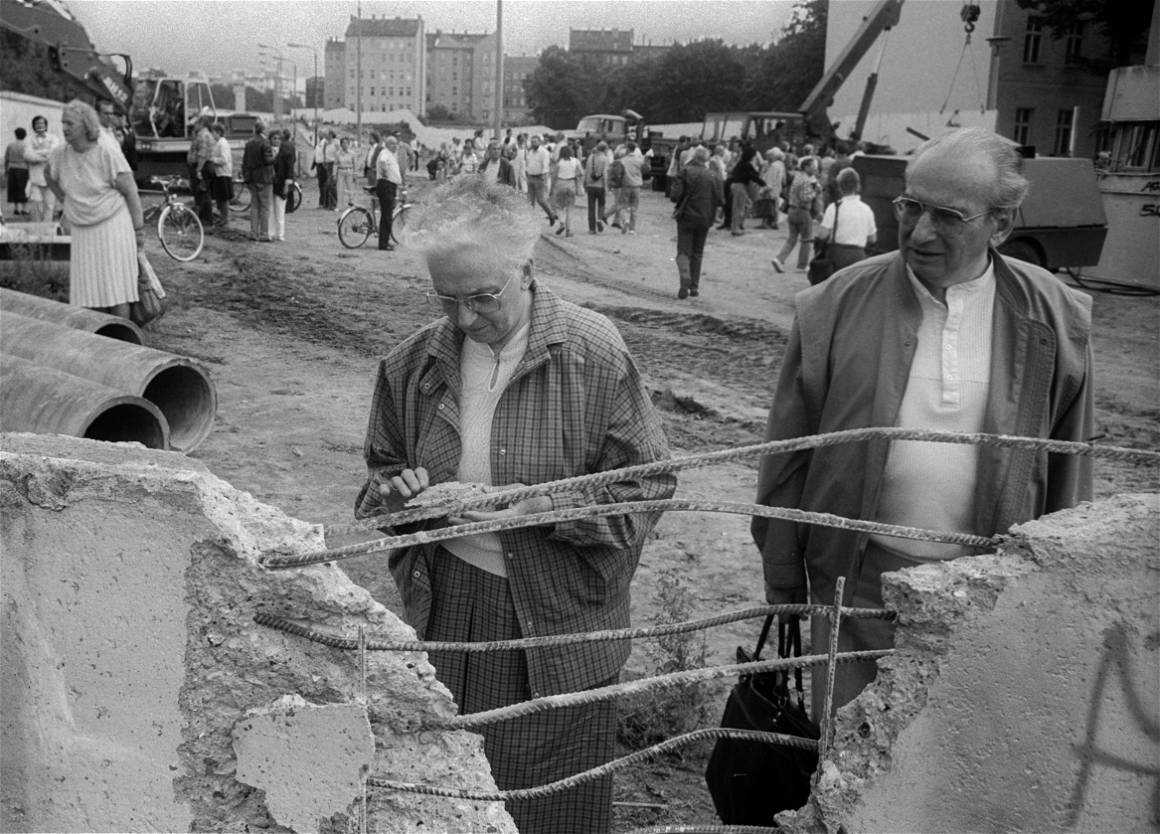

The most outstanding events were probably the Wende events and the fall of the Wall in particular.

After the fears of the Wende had faded, I naturally enjoyed the photographic freedom after the fall of the Wall and tried to capture as much as possible.

What do you remember from when the Berlin Wall came down? Where were you, what did it feel like in the city?

The night the Wall fell, a couple of friends picked me and my girlfriend at the time up in a Wartburg. We drove to the Bornholmer Straße border crossing and “crossed over” at around 11:00. We didn’t really need a stamp in our passports any more – but we had one given to us at the post – 10 years later, during an interview for the Wochenpost, I heard from the “border opener” Lieutenant Colonel Jäger that anyone with a stamp in their passport should not be left behind.

We then went to the KuDamm, celebrated there – some not very good photos were taken – I was too affected. I perceived the night as unreal, as if in a fog. If someone had told me the next day that you were dreaming, I would have believed it.

What did you see, hear, experience or do around the time the wall came down?

In the next few days I did almost nothing but take photographs – I wanted to capture everything, because the events were coming thick and fast.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and initial contact with the editorial staff of the daily newspaper (TAZ), you worked as a freelance photojournalist. To you, what does the role of photography have in society? Has it changed since the time you were photographing Berlin in the 80s and 90s?

In the past, photography was a cultural asset, society has largely accepted that photos are taken, even of people, e.g.: Street photography. Today, it has become difficult to show a picture of our time due to stricter personal rights and digital media. In part, this has taken on hysterical features, with all the understanding of protecting oneself, one’s children, etc. There will probably be mainly embellished photos of our time, which will be released by PR agencies, press offices, etc. Released by PR agencies, press offices, etc.

Can you tell us a story about something you did back then that you feel impacted you either personally, as a journalist or as a photographer?

A story: In 1987, an acquaintance asked me if I could photograph an action with children. They needed documentation about it. A number of pedagogues, teachers, but also architects etc. had joined forces to play with children outside the state regulations. had joined forces to play with children outside of the state regulations: Spielwagen Berlin. It was great fun to see these actions in Prenzlauer Berg, for example: Sredzkistraße or Kollwitzplatz. One of the supervisors was the chief photographer at FF-Dabei, the GDR’s television magazine. He liked the photos and got me my first jobs as a film photographer – so I was able to make a living from photography from then on.

Today, the city is very different. Do you still think that Berlin is iconic today and what are the main three changes in the culture that you see from the 80s and 90s?

Of course, years of upheaval are exciting and a very lively time for photographers. Today, the renovated houses are closed, the partly lawless time is over. The tracks have run in, the gentrified Sredzkistraße is boring. But there are also new things to photograph, the evolving Berlin or photos of the still largely accessible still largely accessible visitors to the Sunday Mauerpark.

Rolf Zöllner is a Berlin-based photojournalist and photographer documenting culture and the life of Berlin through his work. This article is featured and written for the IMAGO Zine #2 | ICONS. Get your copy and subscribe to future issues.