The synergy of Carlos Alcaraz sweeping to US Open glory three days before Roger Federer announcing his retirement wasn’t lost on The Game columnist Andy Murray. Can the Spaniard rule tennis like the Swiss master?

Federer out, Alcaraz in – can tennis’ new star fill the shoes left by the departing king?

Monarchies are, by their very nature, dynastic. The whole point of hereditary rule is that royal families exist for centuries, maintaining the status quo and providing a sense of comforting semi-permanence as a prince or princess ascends the throne hitherto occupied by (usually) a parent. If the United Kingdom’s recent example is anything to go by, there will also be time for myriad acts of performative respect, from the turning off of supermarket beeps to Center Parcs demanding guests “must remain in their lodges” on the day of the departing monarch’s state funeral. The dynasty continues. Simple. Efficient.

The passing of sporting eras is seldom so cut and dried. Whether in team or individual disciplines, the point at which greats vacate their crown is best appreciated from a distance of a few decades, with a healthy dose of 20-20 hindsight. Imperceptible at first, sharpness fades or they age out – Gennady Golovkin’s defeat to Saul ‘Canelo’ Alvarez in last weekend’s world super middleweight bout a case in point – until it becomes obvious the young pretender ascends the throne.

Sometimes, however, the passing of the light is as immediate as it is obvious. Little more than three days after 19-year-old Carlos Alcaraz won the 2022 US Open to claim his first Grand Slam title and become world number one, tennis royalty Roger Federer announced his retirement from the sport, aged 41.

See IMAGO’s US Open coverage and curated collections on Roger Federer.

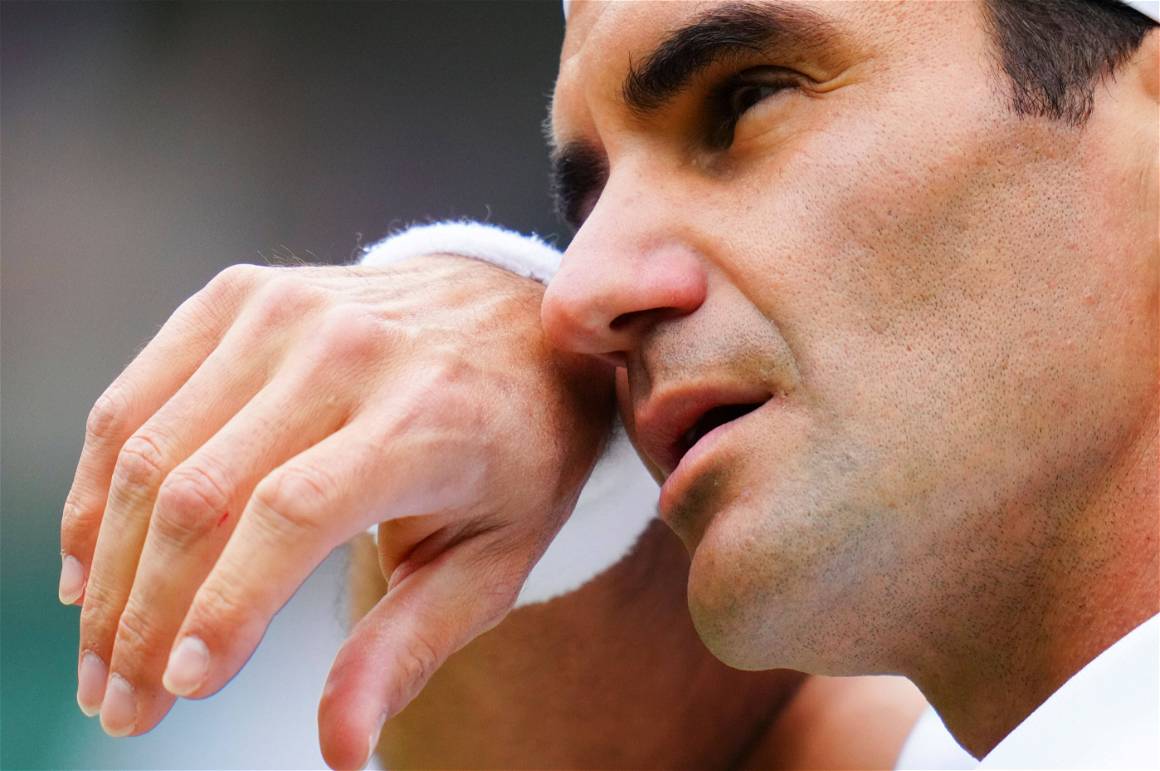

The Swiss, who hadn’t played a tournament since defeat in the Wimbledon quarter-finals in June 2021, is a student of the game and it isn’t hard to imagine him at home in Basel watching Alcaraz’s brutal, bludgeoning ground strokes and thinking, ‘I don’t have this in me anymore’. Within a week, tennis had lost its majesties King Roger and Queen Serena.

“I know my body’s capacities and limits, and its message to me lately has been clear,” Federer announced. “I am 41 years old. I have played more than 1,500 matches over 24 years. Tennis has treated me more generously than I ever would have dreamt, and now I must recognise when it is time to end my competitive career.”

Federer’s last tournament will be the 2022 Laver Cup at the end of September. The 20-time Grand Slam winner deserved a send-off and it’s perhaps fitting that he’ll line up alongside eternal rivals Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray for Team Europe in one of this most individual of sports’ few squad-based competitions. Recovering from knee surgery, Federer can play as much or as little as his body will allow in the less-pressured environment of a competition designed to bring together tennis’ disparate superstars together over the course of three days. It will be the best kind of funeral – light on maudlin mourning and big on celebration of the most talented player to pick up a racket.

Wimbledon may mourn its inability to say an on-court goodbye to its most successful male champion but there is a beautiful poetry to Federer’s final appearance at his favourite Slam being his only straight-sets defeat and ending on the receiving end of his only bagel in the 6-3, 7-6, 6-0 loss to Hubert Hurkacz. Cricketing deity Don Bradman needed just four runs in his final innings in 1948 to finish with a batting average over 100 but was dismissed without scoring to retire on 99.94, a statistical quirk now part of the sport’s mythology. In losing that set to love, Federer served to remind the tennis world just how hard the sport that he’d spent two decades perfecting really is.

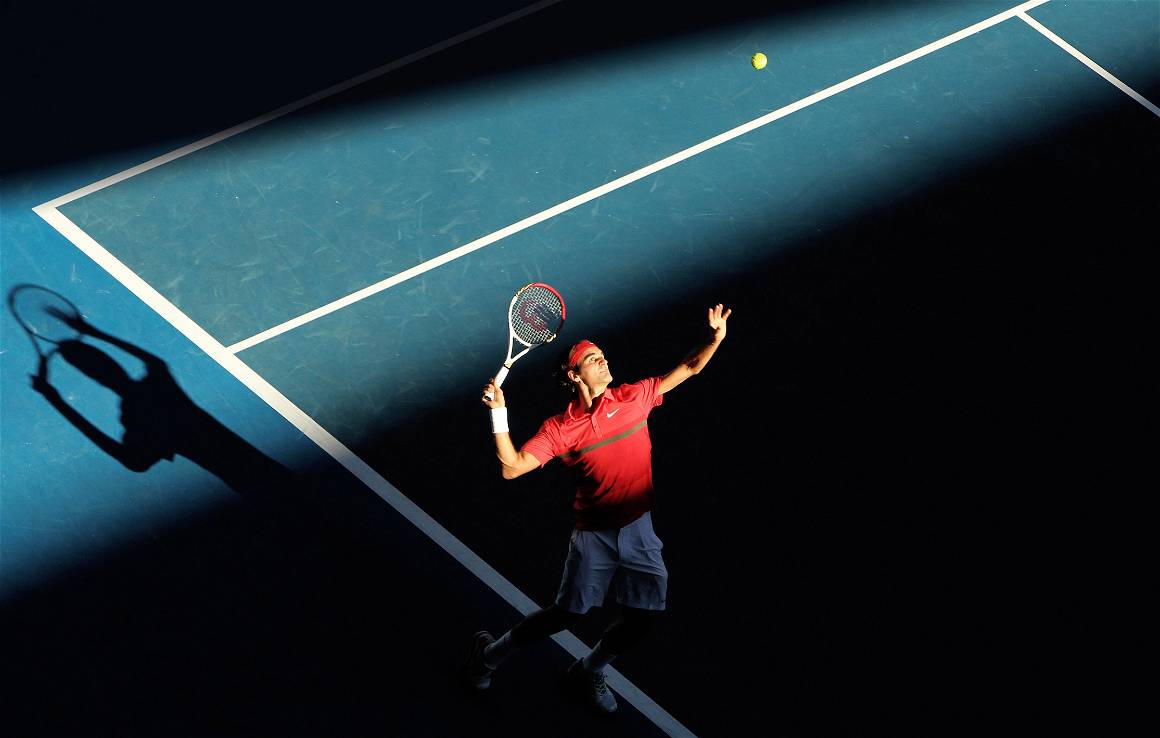

Watching Federer at his best was like witnessing a cheetah stalk its prey – the feline grace with which he eased over the court was matched only by the ruthlessness the Swiss showed in sniffing opportunity for the kill. If Nadal is a superhuman example of what relentless training, preparation and ability to block out pain can achieve and Djokovic driven to the point of self-combustion by winning, Federer was distillation of tennis in its purest form. Effortlessness in excellence is a gift mortals shouldn’t be afforded, yet Federer’s groundstrokes more closely resembled the artistic dash of a Picasso or a flamboyant Nureyev pirouette.

Federer perhaps became more loved the more fallible he got. In disposing of Andy Roddick in seven finals – most memorably 16-14 in the final set of the 2009 Wimbledon showpiece – there was a sense of the inevitable, but as Nadal and Djokovic rose in prominence Federer’s charm shone through. Recovering from a first knee surgery to win the 2017 Australian Open, Indian Wells, Miami, Wimbledon and then retain the former to prove it no fluke was the Indian summer to Federer’s career while holding match points for what would’ve been a ninth Wimbledon in the 2019 final his last shot at the summit. Seven years before that was the last time Federer beat Djokovic in any Grand Slam final.

Federer got the chance to kill his idol in a way Alcaraz never will. The five-set epic against Pete Sampras in the Wimbledon fourth round in 2001 was the first example of what would become the Swiss’ enduring genius. Federer to Alcaraz is more illustrative than that.

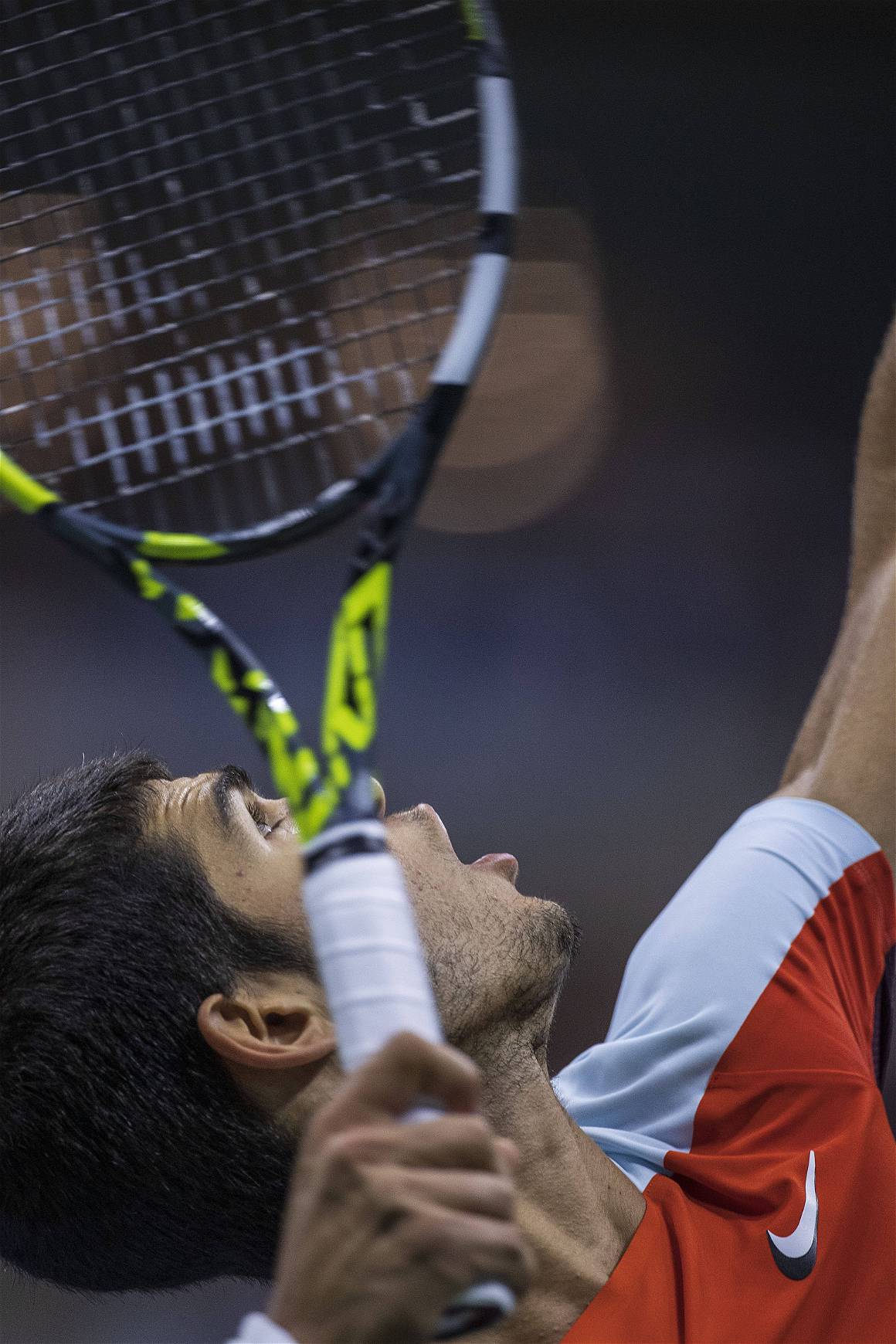

“Roger…” began Alcaraz in a Tweet followed by a broken heart emoji following Federer’s announcement on September 15, “Roger has been one of my idols and a source of inspiration! Thank you for everything you have done for our sport! I still want to play with you! Wish you all the luck in the world for what comes next!”

Federer and Alcaraz – the seventh-youngest Grand Slam champion in history – will never play a competitive match against each other, but tennis’ new king knows that to truly rule he must play, and beat, the other members of the Big Three still standing in a Slam. At Flushing Meadows, the unvaccinated Djokovic was absent because of Covid-19 restrictions, while Alcaraz’s fellow up-and-comer Frances Tiafoe did his dirty work for him by disposing of Nadal in the last 16.

“I’ve always said that in order to be the best, you have to beat the best,” said the still-teenage Alcaraz. “You don’t just click your fingers and have the world at your feet. You have to work at things. I think what I have achieved, winning a Grand Slam and being No. 1 in the world, is because of the work I’ve been doing with my team for a very long time. It hasn’t been a bed of roses, I’ve had to suffer and go through bad times to get here.”

The heir apparent to Federer is here and unlike Alexander Zverev, Stefano Tsitsipasis and even Daniil Medvedev, Alcaraz seems to have the minerals to stay on the throne for some time yet, forging ahead with a new narrative all of his own. The king is dead. Long live King Carlos.

Other previous articles on tennis include:

What Emma Raducanu’s US Open victory means for tennis’ future

Osaka and Williams shifting mental health in sports: impressions from photographers

Racquet Magazine. Celebrating Tennis and the Culture Surrounding the Game.