The beautiful game has reached the point where its most iconic stars are beginning to age out. The Game columnist Andy Murray wonders what football can learn from music as it comes to terms with its legends ageing out.

Pele, Maradona and the Changing Iconography of Footballers in Death

Death is notoriously good for business

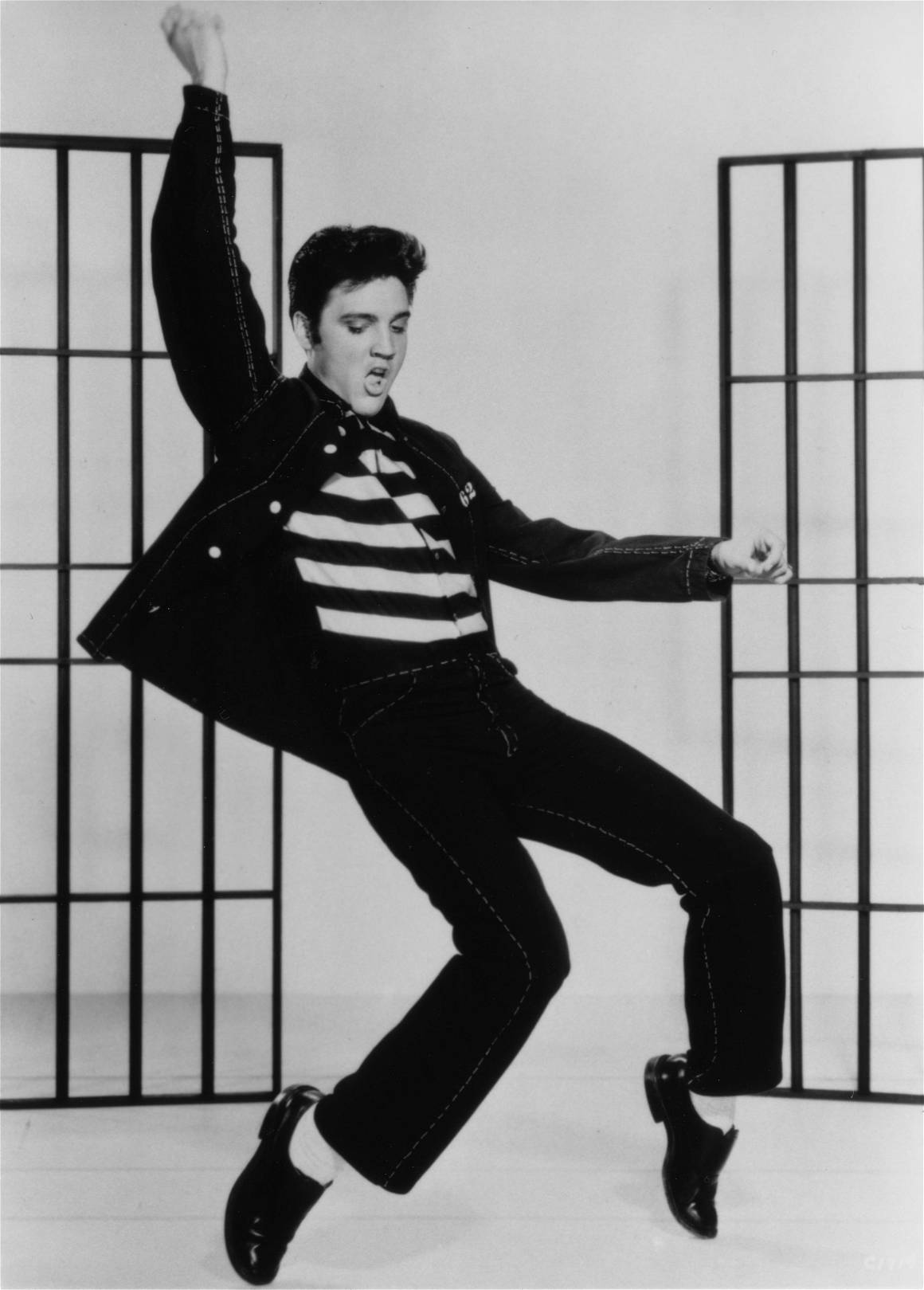

When Elvis Presley went to his bathroom to read in the early hours of August 16, 1977, never to return, his renaissance truly began. Presley’s career had been in decline for some time. The King hadn’t made a truly great record since 1968’s If I Can Dream, record royalties were dwindling, as were live ticket sales, and he was almost entirely dependent on prescription drugs. Worse still, the 42-year-old wasn’t cool anymore, just a washed-up crooner overtaken by the rock stars he’d inspired, from the Beatles and the Rolling Stones to Bruce Springsteen, Elton John and even Fleetwood Mac.

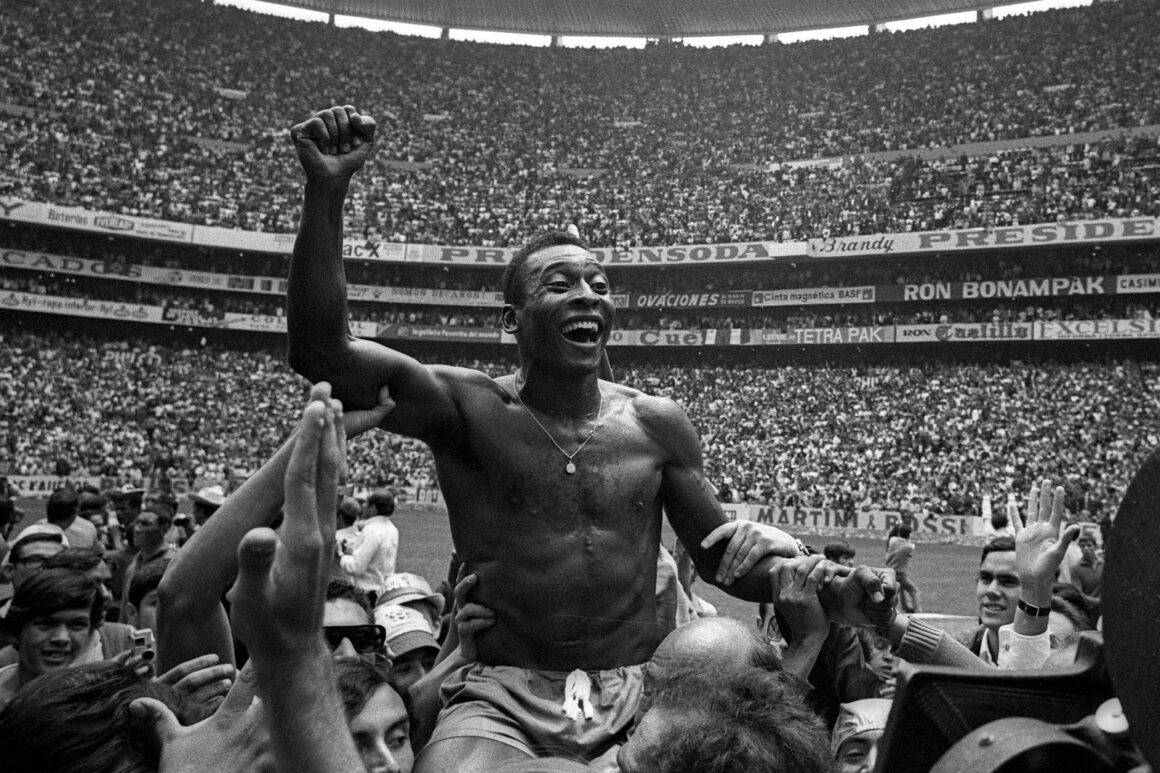

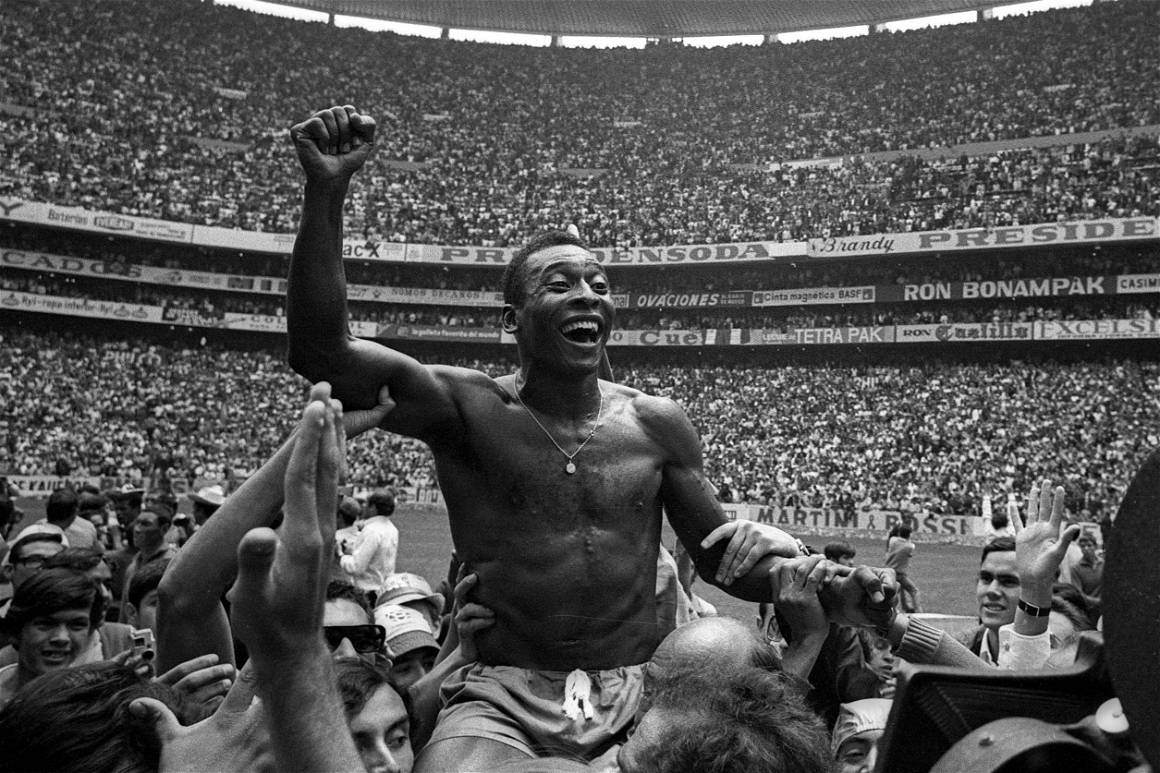

Seven years before Elvis’ death, Pele was voted the Most Famous Person in the World. He had just turned 30 and, a matter of months earlier, had won a third World Cup at Mexico 70. The Brazilian, who died at the end of 2022 at the age of 82, was at the peak of his powers and had ensured his enduring legend in the white-hot furnace of Central America.

In 1958, the 17-year-old Pele had exploded into the World Cup consciousness from the third group game, going on to score a goal in the final of such insouciant grace that he almost single-handedly ended both the curse of the Maracanazo defeat in the 1950 de-facto final against Uruguay and the racist notion that Afro-Brazilian couldn’t be counted upon when it really mattered. In 1962, he picked up an early injury and was absent from the second group game onwards. He was kicked out of the 1966 tournament after a concerted campaign to detach him from his own ankles.

Yet in 1970, he scored four goals (laying on a further six assists), nearly scored from the halfway, bamboozled Uruguay goalkeeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz with a feint so good it would make Houdini blush and forced Gordon Banks in the Save of the Century to keep out his header against England. In the final against Italy, he scored a towering header and provided a further two assists – including a no-look pass for Carlos Alberto’s famous strike – in a 4-1 win. That all of this happened in glorious Technicolor as Brazil’s canary-yellow shirts were beamed into the homes of millions of transfixed fans only added to Pele’s ethereal brilliance. “I told myself before the game, he’s made of skin and bones just like everyone else,” said Italy defender Tarcisio Burgnich at full-time, “but I was wrong.”

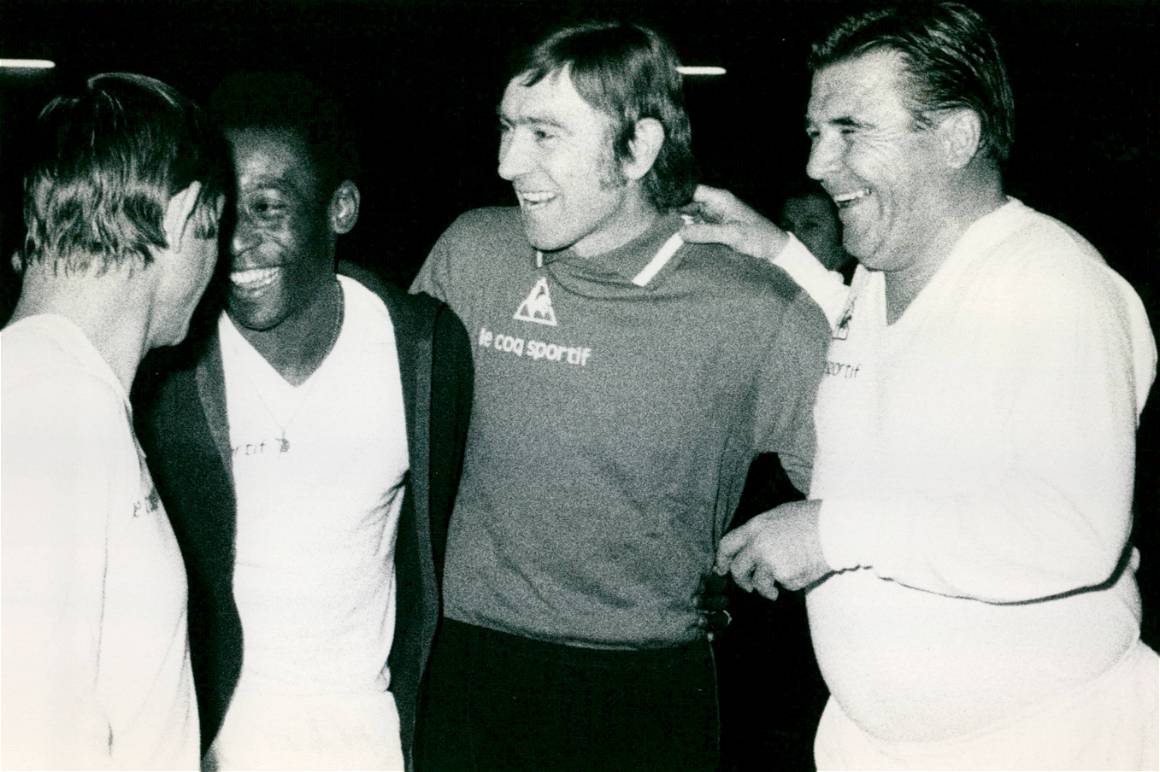

Pele gradually slipped from his apogee of love, respect and awe. As he eased into semi-retirement with Santos and then a spell helping create the hype-machine that was the North American Soccer League with New York Cosmos in the late 1970s, a reappraisal began. Acutely aware of the power of his brand – he was the first footballer to trademark his own name – he took the corporate shilling as the face Puma, Pepsi and latterly Viagra.

He dedicated his 2010 autobiography to disgraced former FIFA president Sepp Blatter. Perhaps beguiled by his New York friend Andy Warhol’s insistence that “Pele will have 15 centuries [not seconds] of fame”, he would attend the opening of a crisp packet if it had his name on it. In 1981, it was inevitable he would star in cult football film Escape to Victory. Notoriously silent on matters political – from his use as a propaganda pawn by the dictatorship of General Emilio Medici in the build-up to 1970, to meeting with less palatable world leaders – the kid born into abject poverty somehow embodied the establishment.

As the years went by, even his own footballing records became a source of tiresome conjecture. For decades the nudge-winks behind Pele’s 1,000 career goals landmark had been a stick with which to beat him. Too many goals against questionable local opposition in Brazil, in European friendlies against travelling sides – as if they somehow didn’t count – and some wags even suggested “goals in training don’t count”. It was yet another indication of someone indulging in the embarrassing act of self-mythologising. It didn’t matter that the millennium goal milestone was a concoction of TV executives to try to persuade Brazilians to buy more TVs and increase ratings, Pele had become Elvis incarnate.

If Pele was football’s first worldwide celebrity, Alfredo Di Stefano was its earliest truly global star. In the 1930s and 1940s England had had Dixie Dean, in Spain it was Pichichi, Argentina had Angel Labruna, and in Italy Giuseppe Meazza, but in an era of the domestic press, each existed in their own microcosm. Di Stefano’s defection from his native Argentina to Colombia and then Spain in the mid-to-late 1950s came at a time when television was bringing continents closer together. That he joined Real Madrid, who went on to win the first five European Cups from 1956 in all-white kits which seemed to come from another planet, helped to confirm his pre-eminence.

Di Stefano died in July 2014, aged 88. The Blonde Arrow was the first of football’s generational stars to age out, with Johan Cruyff, Diego Maradona and now Pele each following as the players most associated with the 1970s, 1980s and 1960s, respectively. Like the music industry – which has lost Jeff Beck, David Crosby, The Specials’ Terry Hall and most recently Burt Bacharach in the past two months alone – football is now old enough for its formative elite to pass away through the passage of time and not an early tragedy.

There have been those, of course. Last week was the 65th anniversary of the Munich air disaster in which eight Manchester United players (plus three members of staff, two journalists and one crew member) died when the aeroplane carrying them back from a European Cup quarter-final in Belgrade crashed on take-off following a snowy layover in Germany. One of the Busby Babes – named after manager Matt Busby, who’d created a vibrant young team that had reached the final four in Europe – was Duncan Edwards, widely believed to be the finest English footballer of his generation who had already made 177 appearances for United despite his tender 21 years. Like the singer Buddy Holly – who almost a year to the day after Munich, boarded a plane in Clear Lake, Iowa, which also fatally crashed moments after take-off – Edwards’ life is now exclusively viewed through the tragic prism of his death, almost with the melancholic purity of a martyr.

Though football has broadly escaped an Icarus in the form of a Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix or Amy Winehouse by dint of its predominant drugs being matchday adrenaline and the thrill of a crowd’s captivation of a player’s every move, when the sport stops it can be difficult to replace. The beautiful game’s enfants terribles Diego Maradona and George Best were functioning addicts (cocaine and alcohol respectively) during their playing careers, but their prodigious gifts were such that they were indulged. Best, a footballing Kurt Cobain beset by competing twin tenets of rabid ego and crippling anxiety, died in 2005 aged 59 after continuing to drink despite a liver transplant five years earlier. Maradona was seven months older when passed away in November 2020 through complications from his own addictions. The singularity of their genius makes their descent all the more heartbreaking.

When it comes to death, legacy is what matters. Goals, assists, clean sheets and even trophies are facile – influence, inspiration and stimulus are far more evocative. Johan Cruyff, who died three months after music’s great iconoclast David Bowie in March 2016, knew that better than anyone. Taking inspiration from compatriot Vincent van Gogh – who came to be impressionism’s founding father only in death, selling just one painting in his lifetime – the Dutchman’s belligerence bordered on intransigence. With the help of Ajax and Netherlands coach Rinus Michels, Cruyff’s certainty in his own divinity delivered Total Football’s positionless fluidity in the 1970s, then managed to do it all over again as Barcelona coach from 1988 to 1996. Success did follow – 36 trophies as player and manager, thanks for asking – but Cruyff’s revolution was stylistic, an intangible to be studied, enjoyed and analysed.

“Winning is just one day; a reputation can last a lifetime,” Cruyff summarised. “Winning is an important thing, but to have your own style, to have people copy you, to admire you, that is the greatest gift.”

And isn’t that really the point? “You need an ending to make a story,” music journalist David Hepworth wrote in his book Uncommon People: The Rise and Fall of the Rock Stars. The changing iconography of footballers to the immortality afforded by their passing matches their rock star counterparts. If Maradona was the John Lennon visionary of seemingly effortless brilliance, Pele was the try-hard Paul McCartney, who your dad probably liked. Like McCartney’s Glastonbury reinvention last summer – unusually achieved while still with us – which featured a Lennon duet from beyond the grave, Pele’s death at the end of 2022 has meant the narrative has rightly switched to the trendsetter whose unique blend of physical gifts and creative flair brought about the modern football age.

“The greatest player in history was Alfredo Di Stefano,” the Argentine’s former Real Madrid team-mate Ferenc Puskas once said. “I refuse to classify Pele as a player. He was above that.”

More articles of Andy Murray:

World Cup 2022: The untold stories by Andy Murray

How does men’s football in the UK learn from 30 years of silence?

Federer out, Alcaraz in – can tennis’ new star fill the shoes left by the departing king?

The agony and ecstasys of the football league play-offs.