The so-called ‘Friendly Games’ may have its detractors and a problematic past, but The Game columnist Andy Murray saw a future for the multi-sport event while spending a month covering everything from athletics to lawn bowls at Birmingham 2022.

Raging bulls, threatened divorce and Ozzy Osbourne: the untold stories of the Birmingham Commonwealth Games.

“Just make sure you show us off, will you?” said our server at Bar Estilo in Birmingham’s shiny Mailbox shopping centre. “This city deserves to be seen.”

It was still more than a week before the actual sport would begin, but this roofer-turned-barman was beaming that a group of around 30 journalists from all over the world had come to Birmingham and cover the 2022 Commonwealth Games. For more than a fortnight, his city was the centre of the sporting universe.

First, let’s deal with the elephant – or perhaps that should be animatronic raging bull, the star of the opening ceremony which now sits in Centenary Square attracting thousands of visitors a day – in the room. By definition, the Commonwealth Games are problematic.

First held in 1930 as the British Empire Games, it sits as an anachronism to the United Kingdom’s colonial past. The brainchild of Canadian sportswriter Bobby Robinson – furious at the mistreatment of his country’s athletes by authorities at the 1928 Olympics, in favour of US competitors – the inaugural Games in Hamilton were intended as a celebration of the benevolence of British rule gradually evolving towards its nations’ independence. Except no African or Asian countries competed, not even India, the supposed jewel in the Empire’s crown.

Fast-forward nearly a century and the rebranded Commonwealth was creaking under the weight of its own history. The 2018 Windrush scandal is a case in point. That thousands of economic migrants from across the Commonwealth, including India and the Caribbean, who had answered Britain’s call for workers in the late-1940s, only to be denied legal rights and were even deported some 80 years later, is proof that its most dominant power continues to exploit the collection of 56 territories.

Barbados became a republic in November last year and no longer has Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state, while Jamaica is seeking reparations for the slave trade and may follow its Caribbean neighbour’s lead. Others could also follow. Meanwhile, Olympic gold medal-winning diver Tom Daley has been forthright on the role colonialism has played in anti-LGBTQ+ laws that still exist in around half of the countries which competed in England’s second city.

The Commonwealth Games Federation is facing up to its colonial past, problems which many agree have no easy solution, as it fights for its very existence. It has stopped trying to compete with the Olympics as the premier multi-sport extravaganza – not least because elite talent such as Daley and Jamaican sprinters Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce and Shericka Jackson swerved the Games. Instead, it has focused on being as intimate as an event with 280 events in 20 sports can be, while also providing a platform for non-Olympic sports such as squash, netball and lawn bowls, all of whom view a Commonwealth medal as the apex of their sport. More medals were available to women than men, a Games first, while the Commonwealths’ 2002 decision to include para sports in the main programme continues to both break boundaries and attendance records. Both are a thing the Olympics could genuinely learn from.

Ticket sales were excellent, some 1.3 million over the 11 days of competition. From the press area’s lofty perch from the second floor of Arena Birmingham, not an artistic or rhythmic gymnastics session went by without vast swathes of people traversing the city’s canals – which count more miles of waterways than Venice – to queue for the action within.

One woman seen most days on the Tindal Bridge to reach Arena Birmingham typified the spirit of the Birmingham 2022. One of the small army of volunteers recruited from across the West Midlands and beyond, she diligently stood with her oversized foam hand high-fiving passing children – and the odd adult who should know better – en route to their day out at the sport.

Decked in a garish orange, grey and baby-blue uniform, these helpers ranged from their late teens to their mid-70s, each one possessing an almost cultish devotion to the city and patiently explaining the way to the nearest toilet, train station or refreshment stand across the city to the incoming throng. I wore the same uniform and had to start wearing a hoodie into the office each day because I knew none of this basic information and could no longer live with the shame of having to disappoint the excitedly expectant faces before me.

The city’s Victoria Square, the site for the finish of the men’s and women’s marathons, was repurposed as a mini-festival site with DJs pumping out tunes into the evening and even the occasional fitness session from British pop-cult icon Mr Motivator. The stately Old Joe – the oldest freestanding clocktower in the world at the University of Birmingham – looked down over the hockey, while the equally red-bricked Jewellery Quarter radiated 19th-century charm.

Whether day-trippers for the sporting jamboree or locals relaxing after a day in the office, the city gorged itself on being the centre of attention. I’ll also confess to doing something similar at the Coconut Tree, a Sri Lankan restaurant I would urge anybody spending more than 10 minutes in the city to visit. Its egg hopper is to die for.

The sport was bright, breezy and fun. Jake Jarman won four artistic gymnastics golds aged just 20, Adam Peaty lost a first 100m breaststroke race since 2014 in the pool and Elaine Thompson-Herah continued her assault on women’s 100m and 200m. Yet these Games were also about stories – 0.5% of Norfolk Island’s total population was representing the former penal colony in Birmingham at lawn bowls – the sort of human-interest pieces that don’t have the room to shine through at modern-day Olympics.

Husband-and-wife Greg and Donna Lobban had to play against each for Scotland and Australia respectively in the mixed doubles squash, Donna claiming Greg would “have to cook dinner for a month” if he lost. “We won’t be signing any divorce papers after today,” she said after her victory with her cousin Cameron Pilley. “We’re still all right.”

Women’s 62kg wrestling silver medallist Ana Godinez Gonzalez fled her native Mexico to Canada at the age of seven when local gangs threatened the family with kidnapping. Her father told her they were going to Disneyland, only to rock up in Surrey, British Columbia.

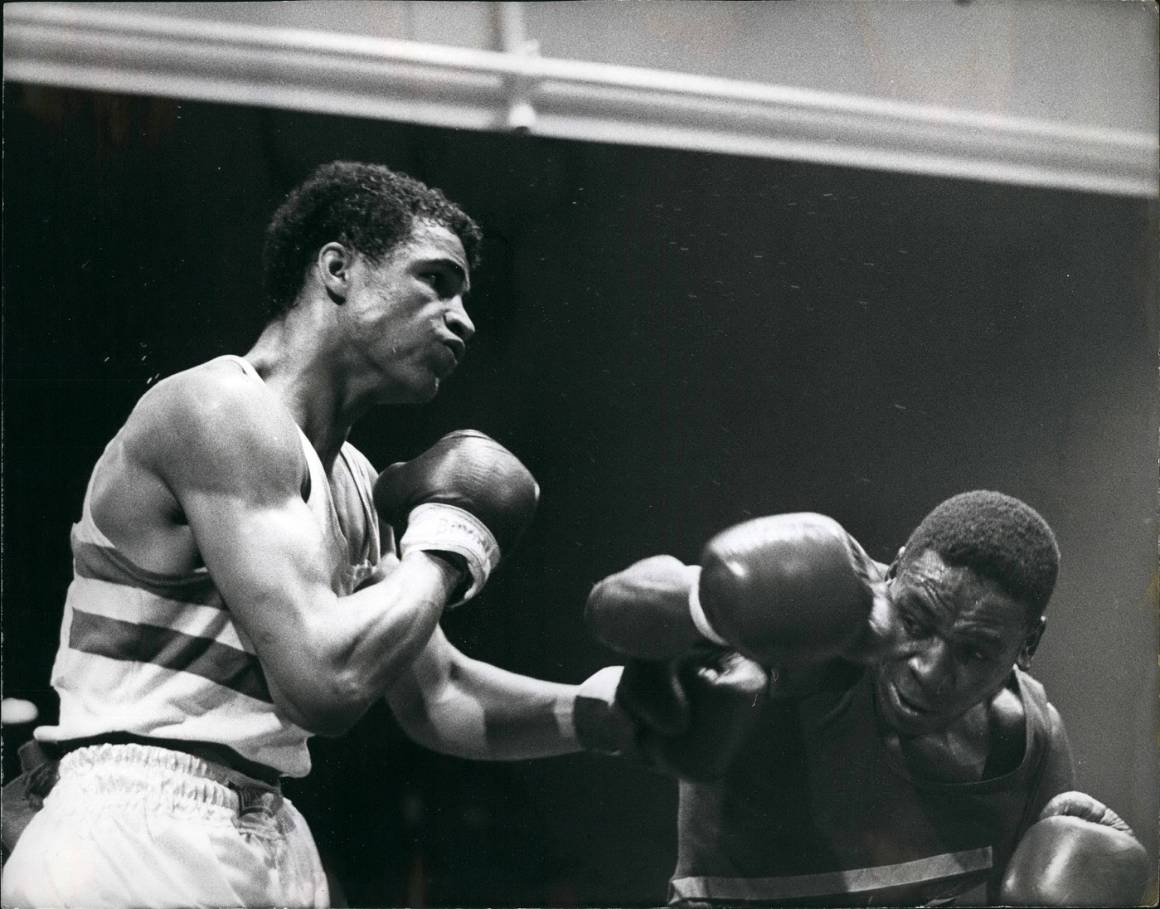

Then there were the myriad gymnasts, boxers, weightlifters and more who couldn’t wait to chow down now their calorie-controlled diets were over post-competition. “I’m going to go out to that doughnut stand and eat four doughnuts,” said Amy Broadhurst after Northern Ireland’s light welterweight won gold. “Wetherspoons will be for later.”

Finally, though, is Rosefelo Siosi, from the Solomon Islands. He finished the men’s 5,000m three laps and 90 seconds behind the rest of the field to a standing ovation from the packed Alexander Stadium crowd. It may have cost north of £780m for a few revamped stadia and an aquatics venue, but for this underappreciated city’s chance to cheer and luxuriate in the spirit of the underdog.

Birmingham, from Duran Duran in an opening ceremony celebrating your pride at being the UK’s most multicultural city to the closing throes featuring Peaky Blinder dances and Ozzy Osbourne closing it all with the rest of Black Sabbath, you were bostin’.

Whisper it, but maybe the Commonwealth Games have a future, after all.