Last month, Jake Daniels became the first active professional footballer to come out as gay in UK football for three decades. The Game columnist Andy Murray asks why nobody before a 17-year-old forward for second-tier Blackpool with one senior appearance to his name felt able to be themselves…

How does men’s football in the UK learn from 30 years of silence?

Bravery is a much-coveted attribute in football. Whether it’s a central midfielder thundering into a 50-50 tackle or Terry Butcher’s famous blood-splattered England shirt, the fabled strongman has been at the forefront of British football’s consciousness since the sport’s earliest beginnings as a rough-and-tumble scuffle on Victorian bogs.

Yet bravery comes in many forms. Only recently has British football begun to deal openly with its mental health tsunami and the devastating effects of coaches convicted of sexually abusing young boys in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Speaking out on a difficult or underrepresented subject? Now that really is brave.

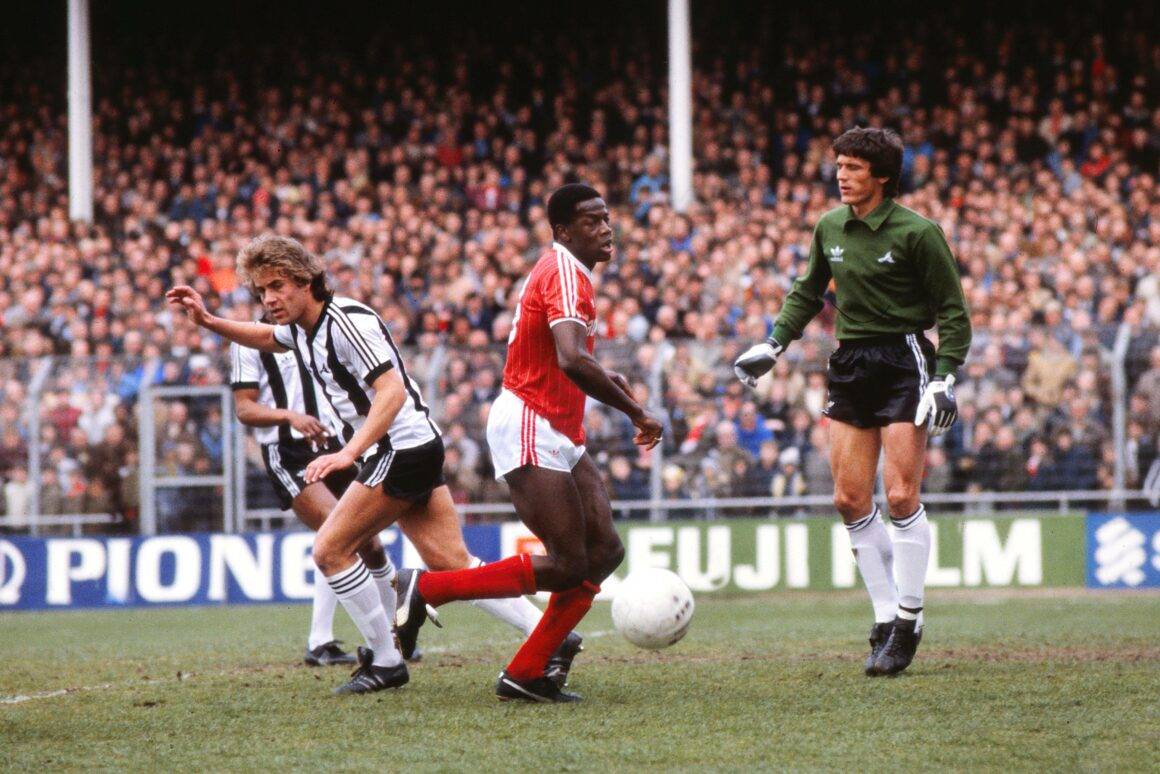

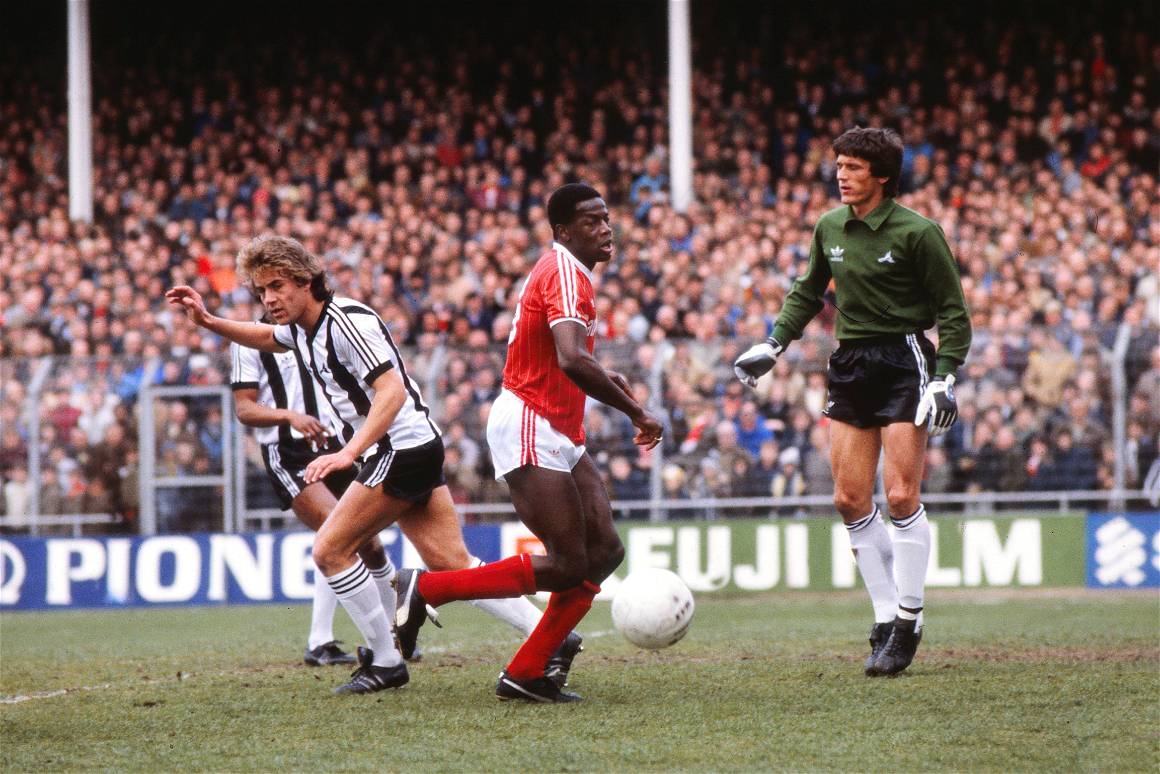

On May 16, Jake Daniels – a 17-year-old Blackpool forward with one senior appearance to his name – became the first active professional men’s footballer in Britain to come out as gay since Justin Fashanu 32 years ago. When Fashanu came out to the Sun in October 1990, they focused on titillating details of affairs with unnamed married Conservative MPs, footballers and pop stars, not the seismic importance of what this moment meant for the gay community and football. The backlash was strong, homophobic and Fashanu struggled to cope, having suffered abuse discrimination for much of his career.

Fashanu’s manager at Nottingham Forest, Brian Clough, later recalled one of their conversations in his autobiography. “’Where do you go if you want a loaf of bread?’’ I asked him,” Clough wrote. “’A baker’s, I suppose.’ ‘Where do you go if you want a leg of lamb? ‘A butcher’s.’ ‘So why do you keep going to that bloody poofs’ club?’” Fashanu committed suicide in 1998.

Thankfully, the response to Daniels’ bravery has been a good deal more progressive. England captain Harry Kane was among the first to tweet: “Massive credit to you @Jake_Daniels11 and the way your friends, family, club, and captain have supported you. Football should be welcoming for everyone.” Manchester City’s Jack Grealish, Burnley captain Ben Mee and much of the wider football world followed suit.

Amal Fashanu, Justin’s niece, who runs a charitable foundation in his name also offered her family’s support. “If my Uncle Justin were alive I know he would have been one of the first people to have contacted Jake to offer his support and best wishes,” she said. “Justin’s wish was to create a society where people could simply be kinder to one another and where bigotry doesn’t exist.”

That Daniels is only 17 and felt empowered to speak his truth is testament both to his own strength of character and the support network he has around him. Blackpool have worked closely with LGBTQI+ charity Stonewall to ensure Daniels has all the continuing support he needs going forward, to go with his family and friends.

Former Manchester United captain Gary Neville, now a successful TV pundit, praised Daniels strength of character, but also football’s inability to establish an environment where LGBTQI+ players feel comfortably coming out. “It is a big, big moment for football,” Neville said. “The game has not dealt with this issue well at all.”

Acceptance is a start, and football grounds have started to become a more welcoming space for LGBTQI+ fans, yet the lack of visibility of out footballers is proof there’s a long way to go. About 2.2% of the UK population identified as LGBTQI+ in the most recent Annual Population Survey, which is about 1.5million people. And yet there hadn’t been an out gay male footballer for 32 years before Daniels somehow felt able to do so? Off the record, there have been hundreds, two of whom have told me so themselves but were understandably scared to go public. Neither have since revealed their sexuality.

Some, such as Thomas Hitzlsperger, chose to come out after they retired but is it that surprising the former Aston Villa and Germany midfielder couldn’t while he was playing?

Former Brazil coach Luiz Felipe Scolari is on record as saying he would throw gay players off his team. Meanwhile, salacious tabloid reporting continues when there’s a whiff of a story, while former Chelsea full-back Graeme Le Saux spent much of his career on the receiving end of homophobic abuse seemingly because he had studied at university, collected antiques and read left-wing paper the Guardian. Le Saux is straight and married with two kids, yet was abused by fans and even Liverpool forward Robbie Fowler.

Then there’s the upcoming prospect of a World Cup in a country where homosexuality is illegal. How could any openly gay footballer, or fan for that matter, feel comfortable going to Qatar in November? That disgraced former FIFA president Sepp Blatter, after awarding the tournament to the oil-rich country, came up with the solution gay fans should “refrain from any sexual activities” is grimly indicative of where certain sections of football administration is.

A paradox faces gay athletes who are yet to come out. They are notable people in the public eye, in some cases adored and loved by vast swathes of the population, yet they don’t know whether such adulation would remain if they publicly revealed their sexuality. That only serves to highlight the seclusion they already feel because they’re unable to be who they really are.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re a teacher, civil servant, basketball player or footballer, not talking about your life with some of the people closest to you – your work colleagues – is an isolating experience,” former NBA star John Amaechi, who came out after he retired, told me in a 2014 interview with FourFourTwo magazine. “Knowing that the second you pull into the car park for work each morning, it will be the last time you can talk about your life, is very difficult, even traumatic.”

Amaechi told me that after coming out in his book Man In The Middle after retiring from the NBA in 2007, he walked down Los Angeles’ airport concourse. A few days earlier, people clambered over railings to high-five him, have pictures with him. Babies were thrust into his hands to for photo opportunities. Yet now, men pointed and laughed. When one little boy stared up at the 6ft 9in giant in awe, the child’s mother “shielded him behind her as if my looking at him would turn her son gay”.

Amaechi, now a psychologist and a leading voice in LGBTQI+ sport, has always maintained the dressing room isn’t the issue.

“A lot of my team-mates knew I was gay, but they just wanted me to play hard and perform well. The problem exists as much with managers, executives and the external factors that would go with an openly gay footballer. If you think you’ll be marginalised or worse by your paymasters, then not even the support of your team-mates, friends and family can help. All your sacrifices could be jeopardised by the close-mindedness of an old, straight, white man with a chequebook. That’s more a factor than any isolated idiot screaming ‘faggot’ at you from the side lines.”

Women’s football has been far better at establishing an environment where LGBTQI+ players feel comfortably to come out. “We have worked hard to cultivate an environment where inclusion, acceptance and diversity is key to a thriving work and performance environment,” wrote Aston Villa’s Anita Asante in the the Guardian. “If you want to get the best out of a person, regardless of their job, they need to be able to be their true selves.”

Asante herself, plus world-leading players such as Megan Rapinoe, Magda Eriksson and Pernille Harder – the most expensive women’s footballer in history – are among those who fly the flag for LGBTQI+ visibility in women’s football.

The rugby player Gareth Thomas has spoken movingly about coming to terms with his sexuality in retirement and the fact that a player from such a macho environment has done so is vital for football. Last year Adelaide United’s Josh Cavallo became the only male top-flight professional footballer in the world to come out as gay and was namechecked by Daniels, along with Olympic diver Tom Daley.

“I am hoping that by coming out I can be a role model, to help others come out if they want to,” said Daniels in May. “I am only 17 but I am clear that this is what I want to do and if, by me coming out, other people look at me and feel maybe they can do it as well, that would be brilliant. If they think: ‘This kid is brave enough do this, I will be able to do it too.’”

Jake Daniels’ bravery is something to be celebrated. Why it took a 17-year-old to break football’s great taboo and become the voice of a generation is another thing entirely. Football owes it to Jake, and the hundreds of players like him who have felt unable to be themselves, to make sure it doesn’t take another three decades for someone to follow his lead. Football is very lucky to have him.