The outpouring of united emotion after the Australian cricketing legend’s tragic recent death, aged just 52, was testament to one of sport’s great entertainers on and off the field. The Game columnist Andy Murray considers the other maverick sporting geniuses whose everyday appeal charmed fans worldwide.

Shane Warne and sport’s greatest everyday geniuses

The thing about Shane Warne was, you thought he was your mate.

Even, as an England cricket fan, when the bowler’s beguiling leg spin was destroying any remote chance that Australia wouldn’t roll us over in the ‘90s and early ‘00s, Warne still felt a bit like your older brother putting you in a fraternal headlock. Sure, you’d rather he didn’t grab you round the neck and ride his knuckles up and down your temple as if trying to erase a particularly persistent pencil mark, but somehow this was a cathartic process which you missed when it wasn’t there. The outpouring of emotion since the 52-year-old’s heart attack in early March is proof.

The secret of Warne’s charm was his self-aware ebullience. The slightly podgy kid from Upper Ferntree Gully in the suburbs of Melbourne knew he’d been blessed with a once-in-a-generation talent – Google ‘Warne Ball of the Century’ if you don’t believe me – and combined cricket’s trickiest art form with an off-field charisma that fluffed his talents up, but with a wink to let you know he was making the whole thing up.

Not an Ashes series approached without Warne claiming to have ‘invented’ a new delivery – the flipper, top-spinner, slider, or zooter. He knew none was particularly different to the last, but this was all part of game to get inside a batter’s head. When Warne found out South African batter Daryll Cullinan saw a psychiatrist to help prepare for an upcoming encounter, the bowler greeted Cullinan to the crease with the infamous line: “What colour was the couch?” Yet he was also unfailingly magnanimous on the rare cases his team lost. Battle hard, play hard, offer respect when it’s due.

That Warne loved a drink, smoke and preferred chips, pizza and white-bread cheese sandwiches to a modern sportsman’s diet – “if I don’t have my chips, I’m not happy. And if I’m not happy, I don’t bowl well” – made him accessible and human.

What follows may not be the greatest or most successful sports people of all time – though plenty are in the conversation – but, like Shane Keith Warne, their everyman spirit makes them universally adored…

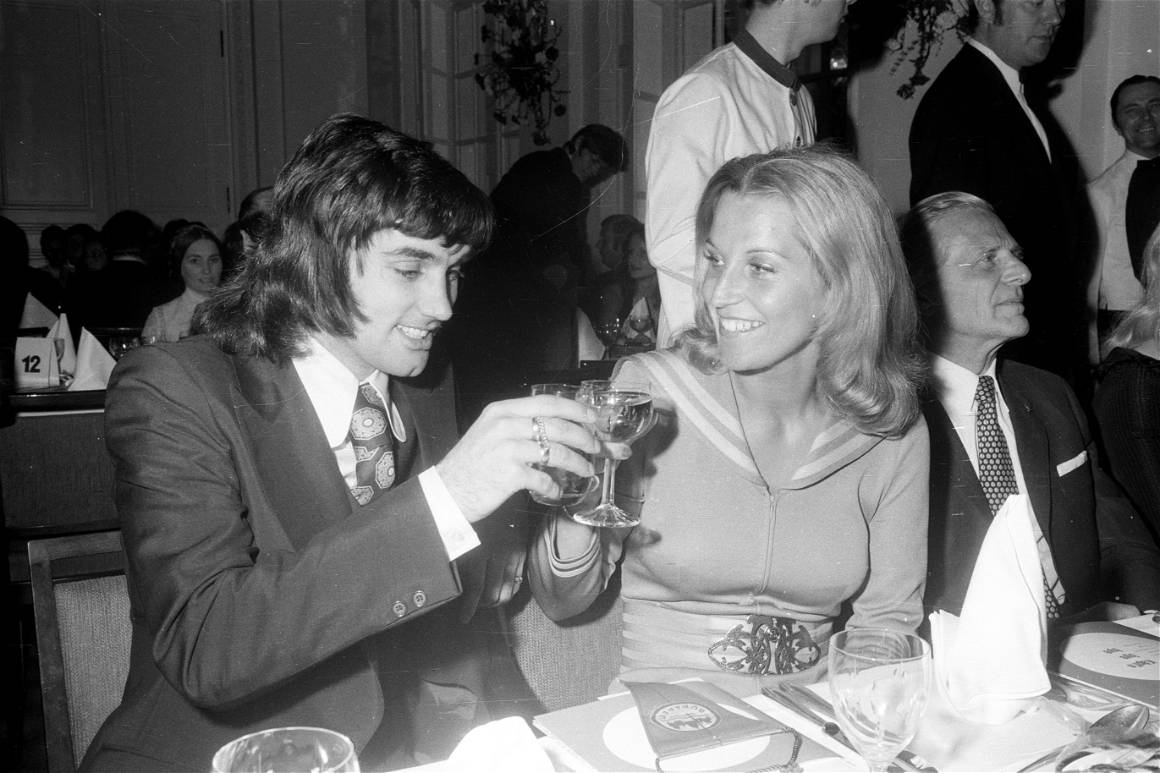

George Best

It all began with a telegram Manchester United’s Belfast scout Bob Bishop sent to Matt Busby in 1961: “I think I’ve found you a genius.” George Best was more than just a supernaturally gifted winger, a Renaissance artist in an era of mud-cake artisans, who won two league titles, a European Cup and the 1968 Ballon d’Or at Old Trafford.

Born on a Belfast estate, the Fifth Beatle was British football’s first crossover footballer – handsome and charming, he mixed with film stars, pop stars and opened his own nightclub, Slack Alice, in Manchester. Best’s descent into alcoholism is well documented, his quips – “in 1969 I gave up women and alcohol, it was the worst 20 minutes of my life” – a cry for help as celebrity culture consumed him. More than 100,000 lined the Belfast streets to mourn his death in November 2005, aged 59, while the city’s airport now bears his name. He connected with people

Pele good, Maradona better, George Best.

Usain Bolt

Sometimes, only McDonald’s chicken nuggets will do. At the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, Usain Bolt ate 1,000 of them over the course of a fortnight after having a less-than-pleasant reaction to a Chinese meal when he first arrived at the athlete’s village. And won 100m and 200m gold, breaking the world record in each.

“Knowing I could rely on nuggets, I made up my mind that was all I would eat,” Bolt recalled in his autobiography The Fastest Man Alive. “And eat them I did, for breakfast, lunch and dinner, washed down with bottled water.”

So, the next time you’re face-first in a box of deep-fried poultry goodness and about to fall down a guilt wormhole, just remember – if it’s good enough for Usain…

Kelly Holmes

Not even Kelly Holmes could believe it when she crossed the line in the 800m final at the 2004 Olympics. Her arms outstretched, Holmes’ face suddenly fell as she doubted whether she had just won gold. “You’ve won it, Kelly!” screamed former 1,500m world champion Steve Cram down the BBC microphone, his voice crackling with emotion. “You’ve won it!!”

Cram knew what she’d gone through and how she was feeling. After years of injury problems clipping her undoubted talent, Holmes was certain that something would happen again to deny her Olympic destiny. A matter of days later, she ran another impeccably timed race to surge to 1,500m gold down the home straight and add another gold to her Athens haul, aged 34.

Holmes has since spoke movingly about her struggles with depression and self-harm, and how she used to make “one cut for every day I had been injured”. She now uses her experience to mentor elite athletes on improving their mental health.

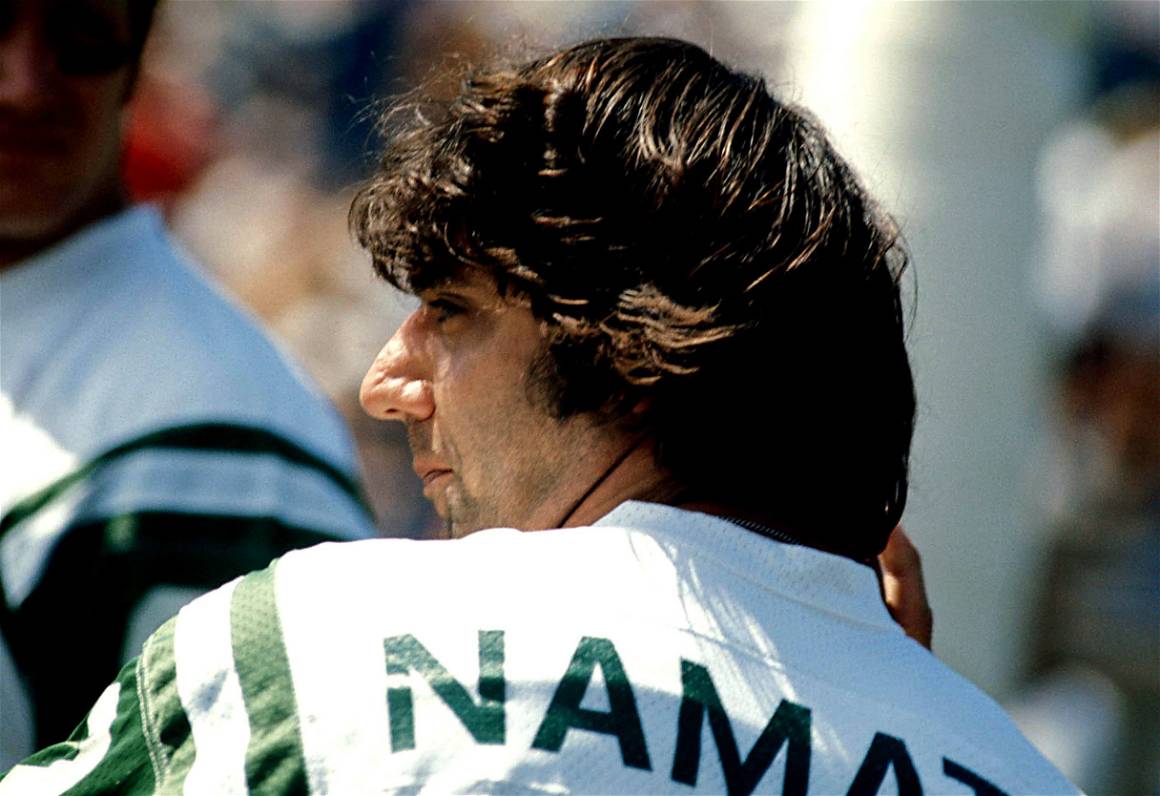

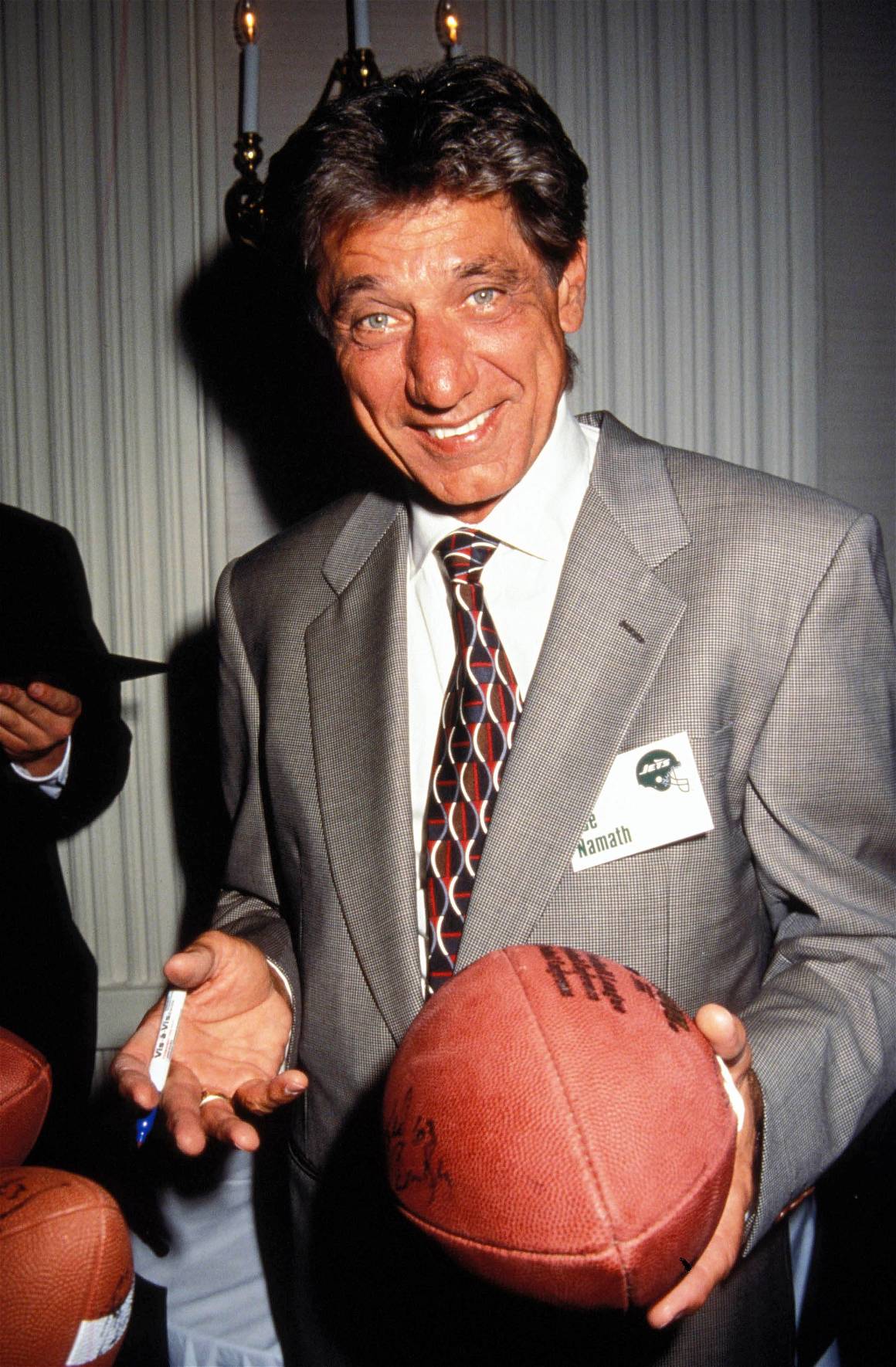

Joe Namath

Joe Namath only won one Super Bowl, but that 1969 triumph was enough to ensure his legacy. AFL champions the New York Jets were as heavy an underdog as you could get against NFL champions Baltimore Colts, the general consensus being that the latter league was the dominant partner in the upcoming merger.

Sick of being told his side stood less than no chance, Namath snapped at a heckler at a pre-game sports banquet. “We’re gonna win the game,” he thundered. “I guarantee it.” Namath completed 17 out of 28 passes for 206 yards to secure a 16-7 victory and ‘the guarantee’ soon entered NFL lore, helping the AFL to parity when the fully merged NFL began the following season.

The son of a steelworker, Namath always retained his everyman, tell-it-how-it-is vibe even when fronting his own talk show, pursuing an acting career and opening the Bachelors III nightclub on the Upper East Side that drew big names in sports, entertainment, politics but also organised crime which ensured its closure.

No matter what, everybody loved Broadway Joe.

Bjorn Borg

Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal fans may disagree, but no tennis player before or since has matched Bjorn Borg’s allure. Far from a down-to-earth everyman, Borg was different, but that didn’t stop half the planet wanting to be Borg in the late-1970s.

The first man in the Open era to win 11 Grand Slam singles titles, including six at the French Open and five in a row at Wimbledon from 1976, Borg’s leonine gait and model good looks belied the power and top spin he added to the sport. His calm demeanour – so noticeable it was widely believed, but later disproved, he had a resting heart rate of just 35 beats per minute – helped him outlast nearly all contemporaries, allied with a self-belief that bordered on the messianic.

That he retired in January 1982, at the criminally young age of 26, only added to the legend. Borg didn’t want to play anymore, so he stopped and set up a clothing range that, for a while, was second only the Calvin Klein in his native Sweden.

Stephanie Gilmore

I’m probably biased, given I spend my summers pretty much living in the sea, but surfers are just cool. And there’s none cooler than Stephanie Gilmore. The seven-time world champion is pure style on a board, hardly surprising given she modelled herself on surf gurus Joel Parkinson, Mick Fanning and Dean Morrison, but it’s how she incorporates that to competitive surfing that blows the mind.

Cool, calm, collective and oozing Australian effortlessness – it’s not for nothing she’s simply nicknamed Happy.

Barry McGuigan

Other boxers have won more, Muhammad Ali is a cultural icon who transcends the sport, but what Barry McGuigan did in 1980s Northern Ireland is perhaps the ultimate example of a regular lad made good.

As the Troubles raged, McGuigan did what no politician could – stop the fighting between Protestants and Catholics. At a time when bombings from both sides were commonplace across the United Kingdom, the Catholic McGuigan married Sandra Mealiff, from a Protestant family, and by not wearing the trappings of either side – particularly the green and gold a Catholic fighter from Northern Ireland may traditionally wear – the featherweight earned respect and an enormous fanbase from both sides. His heady nights a King’s Hall, Belfast brought solace and escapism.

“The shadows ran deep,” he later recalled. “And my fights felt a little like sunshine. Both sides would say: ‘Leave the fighting to McGuigan. You see, it was also entertainment – people loved to forget the Troubles a while.’”

After winning the WBA world featherweight title in June 1985, his BBC Sports Personality of the Year award was inevitable. Uniting a divided country, even if for 12 brief rounds, far less so.