The fan is an intrinsic, irreplaceable part of sport. Without the humble observer, elite competition becomes an unrelenting trudge to the bottom line – a sterile pursuit of results and ever-diminishing (or increasing) numbers.

FANsided, Words by Andy Murray

Featured and written for the IMAGO Zine #1 | FANsided. Get your copy via the link here.

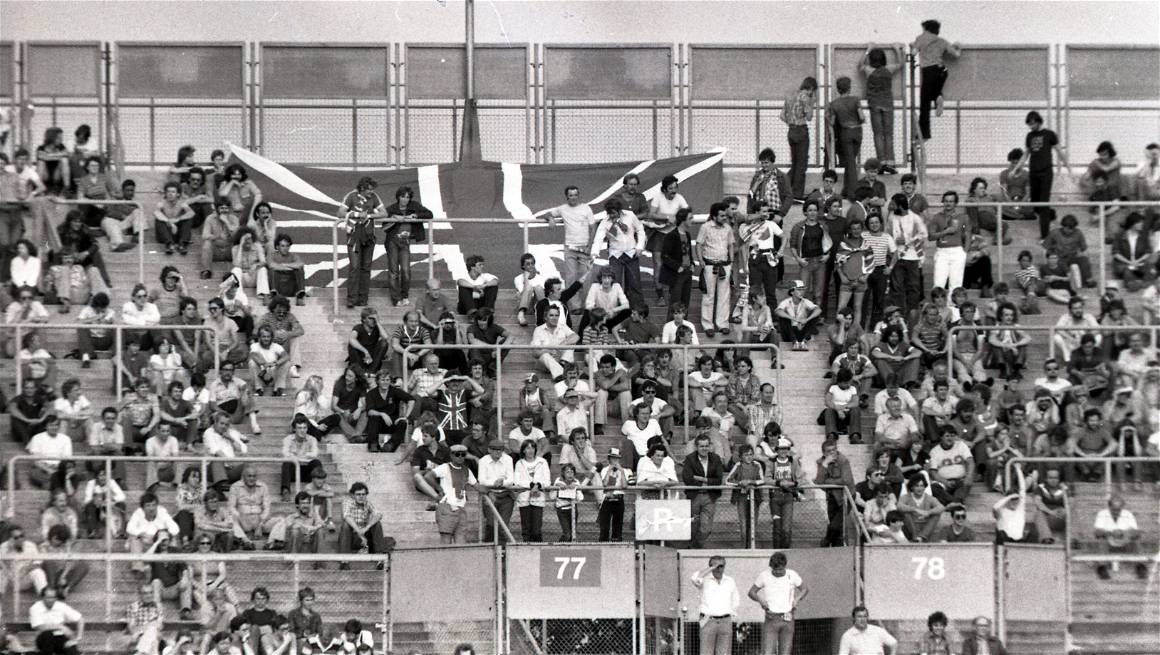

Fans may range from the raucously partisan to the curiously indifferent, but the mere act of congregation, of an elemental shared experience, is something sport has missed more than anything during the pandemic. Bar the first few weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak last spring, sport itself has adapted where necessary to continue, but the febrile intensity and the sense of belonging which had accompanied it for more than 2,500 years has gone.

The Ancient Olympic Games featured 45,000 onlookers on a sloped embankment from 350BC. Built nearly 200 years later, ancient Rome’s Circus Maximus had space for 250,000 spectators, about one quarter of the city’s population. It hosted athletics, chariot racing and ‘damnatio ad bestias’, the ‘condemnation to beasts’ whereby criminals and Christians were thrown to bears and lions.

Ritualistic slaughter may be slightly less palatable to modern, less blood-thirsty crowds but it is from these beginnings which modern fandom derives. The stadia have become more comfortable, but the basic connection garnered from watching a team or individual had remained until coronavirus forced a fundamental reassessment of how fans invest in sport.

Then came the calamitous power grab by the European Super League’s 12 breakaway football clubs, which has betrayed a once unshakable bond. Is it becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish a club from a brand, and a fan from a consumer?

Without baseball, fans would not exist. Or, at least, they would be called something else.

Most sporting enthusiasts were described as spectators or supporters before US newspaper columns began to use the contraction of ‘fanatic’ from the late 1890s. The 1900 edition of language usage journal Dialect Notes features the entry: “Fan, n. A baseball enthusiast; common among reporters.”

The term soon became an intrinsic part of the sporting lexicon. Newspapers played a vital early role in allowing supporters to follow their teams when not physically present themselves, but the voice of the fan was restricted to disparate groups in smoke-filled bars and pubs or factory floor gossip.

From the mid-1980s, football fanzines changed everything. Taking their cue from homemade comic and punk rock titles decades earlier, these often-crude self-published efforts offered a hyper-local, in-depth focus on single teams. While newspapers needed to maintain good relationships with clubs, the fanzine could shoot from the hip and fans could read (and write) honest opinions. A cultural phenomenon, with an underground network of matchday sellers that extended to independent record stores, was born. Fans had a collective, coherent and comedic voice.

“Fanzines gave people an outlet which they didn’t have at that time,” said Peter Hooton, the editor of influential Liverpool fanzine The End, and later the lead singer of The Farm. “Nowadays everyone has a voice on Twitter.”

The internet has democratized fan content. Twitter, Facebook and beyond, YouTube fan channels supersede official club offerings with their big opinions, while podcasts continue to mushroom as equipment becomes more ever-more affordable for DIY creators.

Fanzines were quick to embrace technology, initially in the form of their own websites. Increasingly, they are also partnering with umbrella content outlets, from Rivals.net in the UK, to SBNation.com in the US and the German behemoth that is OneFootball.com, which provide a platform for all manner of club-specific sites from around the world. So successful have these sites become in monetizing fan content, brands from car manufacturers to drinks companies flock to these producers to put together sponsored packages and take advantage of the ready-made audience at their fingertips.

Now, the clubs themselves also want a piece of the fan engagement pie. Tottenham Hotspur, the German Football Association and Borussia Dortmund each signed on as OneFootball shareholders in March, joining Barcelona, Real Madrid, Liverpool, Bayern Munich and other elite clubs in working with the site.

Football fandom leads the way in evolving into a truly global enterprise. The Superbowl may claim the biggest single sporting audience each year, but the hangover of American football, baseball and ice hockey looking almost exclusively at domestic audiences throughout the 20th century allowed the beautiful game to dominate.

The English Premier League has provided the model for other countries, and even sports, to follow. Promising greater riches for the elite, its 1992 breakaway recognized theirs was a marketable product that could attract significant global interest with the help of satellite television.

Lucrative pre-season tours across the United States and the Far East have opened up new markets, bringing players closer to fans who regularly get up in the early hours of the morning to watch their heroes on either expensive television subscriptions or via illegal online streaming. Arguably, they are more dedicated than the fan who wanders half an hour across their home city to watch their side in person. They will certainly spend more money.

In Spain, La Liga have started scheduling matches to make kick-off times more appealing to fans in the Far East. It’s worked – Real Madrid and Barcelona have more than 250 million fans worldwide, over 100 million more than Manchester United. More fans have meant more money, with Spain’s big two now topping the Forbes list of most valuable football clubs at more than $4.7 billion ahead of Bayern Munich and the Red Devils relegated to fourth.

An increase in exposure and revenue leads to a rise in responsibility. Clubs have come to feel more like brands in themselves, the visibility and marketability of their image more important than anything. Desperate to appeal to as many fans – and/or consumers – as possible, clubs are quick to enroll their players in media training to sanitize their output. The disconnect between elite athletes and the public has seldom been greater. Football is beginning to recognize this and personality is once again infiltrating content, but interviews with top stars in tennis, rugby union, cricket and most American sports are notable for their lack of interest.

The ravages of commercialization on elite sport only add to the disconnect with older, fiercely loyal and frequently working-class fanbases. Manchester United’s commercial arm is again the prototype. They have 23 global partners (including pillow and wine partners), three regional partners (one an official indoor entertainment partner just for China), 14 financial partners from Mexico to Myanmar and 15 media partners for its MUTV output.

Sport’s increased commercialization has meant new verticals for fan content. Detached from the athletes and teams, younger audiences increasingly support clubs via the prism of fan TV channels on YouTube, which offer a brash, blinkered and unfiltered view of fandom far removed from official outlets. AFTV is perhaps the best known, beginning life as a YouTube Arsenal fanzine, talking to fans immediately after games, providing watchalongs and interviewing past players.

The goal, however, has become to monetize opinion, no matter how toxic. Outlandish statements matter because they can be clipped up and put on social media, driving engagement and therefore advertising revenue. It doesn’t matter if the YouTuber in question believes what they’re saying, as long as it ‘does numbers’ on social media. Mark Goldbridge, the face of AFTV’s Manchester United equivalent The United Stand, is actually a former police officer from Nottingham called Brent Di Cesare who inhabits the sort of frothing character demanded from such channels.

Tribalism, as opposed to open-minded fandom, becomes normalized on social media, too often at the expense of standing up for vital societal campaigns such as Black Lives Matter and mental health awareness. Adopting a contrarian viewpoint trumps all.

YouTube personalities are even making moves into the sporting arena itself, bringing their army of fans with them. Logan Paul – a one-time star of Disney series Bizaardvark, who has been making YouTube video’s since he was 10 – is a motormouth vlogger who has recently attached himself to boxing. The Gen-Z public can’t get enough. Subscribers get a front-row seat to training camps, making Paul’s brash call-outs accessible in a way elite boxers aren’t.

Aged 26, he is worth $19 million and will fight 50-0 hall-of-famer Floyd Mayweather in an exhibition bout on June 6.

The show itself will closely resemble his younger brother Jake’s fight against former MMA star Ben Askren in April earlier this year. Part of an off-shoot of boxing which is as much about entertainment as the sweet science itself, it generated 1.5 million pay-per-view buys for up-and-coming video streaming service Triller, making it one of the top 10 all-time. Paul is the third-highest earning boxer in the world in the past 12 months, having also beaten former NBA star Nate Robinson. Only pound-for-pound king Canelo Alvarez and world heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua earned more.

Primed for the 15-24 market, the undercard featured short sets from Justin Bieber, Doja Cat, the Black Keys and Mt Westmore, the recently assembled hip-hop supergroup comprising Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, Too $hort and E-40. Expert commentary came from Snoop himself, Saturday Night Live star Pete Davidson, former WWE wrestler Ric Flair and a seemingly well-lubricated Oscar de la Hoya.

Sports are desperate to keep up in the contest for young pairs of eyes, all potential future fans for life, but face competition with TikTok, computer games and YouTube. Crossover Gen-Z talents like Ryan Garcia – the WBC interim lightweight champion, who documents his career and ridiculous hand speed to tens of million of fans on Instagram and TikTok – help, but sports are becoming increasingly unashamed in their attempts to woo the youth.

In January 2021, NFL on Nickelodeon simulcast the Chicago Bears v New Orleans Saints wild card game to make the game more appealing to the child market. Former NFL wide receiver Nate Burleson, Nickelodeon star Gabrielle Nevaeh Green, 15, and sports broadcaster Noah Eagle explained rules, game mechanics and jargon, to go with virtual slime cannons that erupted after touchdowns, colorful animations and SpongeBob Squarepants-adorned goal posts.

Blissful in its restrictive isolation for so long – only taking games abroad with any regularity since 2007 – the NFL hope to expand to have a London franchise from next year, after the sell-out success of the International Series at Wembley and the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. What is most surprising is that the franchise model – with teams regularly moving around the States – hasn’t been more open to such expansion and new markets before.

Some sports have gone as far as reinventing their own rules. Debut competition The Hundred has courted consternation from the cricket establishment for fundamental changes to the sport’s 233-year-old laws of the game in a new format to take place in UK summer holidays with live music performances to attract the youth market.

Even individual sports like tennis, snooker or darts – where fans attend more for the spectacle than following the participants themselves – are trialing shorter formats (from shorter sets, to shot clocks or one-frame shootouts) in the belief they will appeal to the next generation of supporters.

All of which brings us to football’s European Super League. Elite clubs have always struggled with the sport’s lack of the economic principle of appropriability – in short, it can’t make (appropriate) money from more than a tiny share of our combined love for football.

Their plans accelerated by the pandemic, 12 breakaway clubs – from Real Madrid and Barcelona in Spain to the Milan clubs and the Premier League’s so-called Big Six – attempted a power grab in April to start a new continental league which ringfenced the founder members’ continued participation. Perhaps it was no surprise – the 18 Premier League clubs to release 2019/20 accounts average weekly operating losses of £1.25 million. But it is further down the pyramid where the pandemic’s effects are keenest felt by Football League clubs fighting day-by-day for literal survival because fans cannot attend.

Promised $5 billion by US banking giant JPMorgan Chase to arrest declining viewing figures, diminishing TV rights deals and the COVID-enforced absence of fans in stadiums, the clubs professed “to save football” according to project chairman, and Real Madrid president, Florentino Perez.

According to Perez, football has four billion fans around the world – the majority called ‘legacy fans’ who would remain regardless – but 40% of people between 16 and 24 were no longer interested and that interest was declining. “By 2024, we’re dead,” he said. “Football has to change and it has to adapt.”

Perez also announced plans for shorter games because that youth market couldn’t concentrate for 90 minutes. The image of a 74-year-old emperor, worth over €1.5 billion, telling young fans how they engage with football couldn’t have been more illustrative of his natty new clothes. No longer could fans convince themselves their owners were mere custodians, but the sporting equivalent of GameStop short traders on the ever-turning money-making train.

The legacy fans rebelled. So did the vast majority of current and former players and even hitherto football-phobic politicians.

Protests at grounds from Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge to the concerted efforts of Manchester United fans to disrupt fixtures have put plans on hold in a sign of what a united front can achieve. Liverpool and Spurs fans are demanding representation at board level to ensure there is no repeat of April’s antics and have forced groveling apologies from management level.

The backlash in Spain, however, has been nowhere near a vitriolic. Used to Madrid and Barça effectively holding the rest of La Liga to ransom, Spanish seem grimly acceptant of the Super League’s eventual triumph.

Many want to maintain the momentum by enforcing Germany’s 50+1 rule. There is a parliamentary debate in the UK due for June 14 about the realities of forcing owners into giving up 49% of their clubs. Some in Germany actually believe the fans have too much power – they’ve interrupted matches by throwing tennis balls onto the pitch in protest at Monday evening games – but it’s no coincidence Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund were two of the biggest clubs to publicly decline the Super League’s advances.

Sport’s Faustian pact with money has turned sports teams and athletes into brands, but the pandemic has proved how just how essential it is to keep fans, not consumers, onside. In an ideal world for the elite, their consumers are desperate for any content they get, but they have found that even the legacy fan can only be bought so far.

“The vast concourse of spectators is in possession of a great power which, when wielded with wise discretion, may produce incalculable benefit,” wrote the Yorkshire Post in 1882.

After a year in the abyss, some clubs would do well to remember the influence fans have or revolution may be afoot.

Andy Murray is a sports writer and columnist for The Game. This article is featured and written for the IMAGO Zine #1 | FANsided. Get your copy via the link here and subscribe to future issues.