Plans for a breakaway super league stimulated a fan uprising and rocked European football last month. As fans, politicians and players alike united in outrage, the world was reminded of the position of the football fan and the undeniable culture that encompasses the game. Sam Hudspith looks back on a week of unease for football’s richest clubs.

The Position of Football Fans in the Modern-Day

For the Many, Not the Few: The Position of Football Fans in the Modern-Day by Sam Hudspith.

Now that the dust has somewhat settled on the infamous Super League proposals and subsequent fan, media, player and club revolt against them, we can begin to look at the plans a little more objectively. It is undoubtedly that the Super League was a simply terrible idea, yet it brought about an important discussion – the power of the football fans in the modern-day game.

‘We pay your wages’. ‘Without fans, football is nothing’. ‘Created by the poor and stolen by the rich’. These are all statements that were made on social media, by players, fans and the media alike, during the short-lived Super League fiasco. The factual truth within these statements is up for debate, but the sentiment is very real. Football, especially this year, is becoming more ‘corporate consumerism’ and less ‘for the love of the game’.

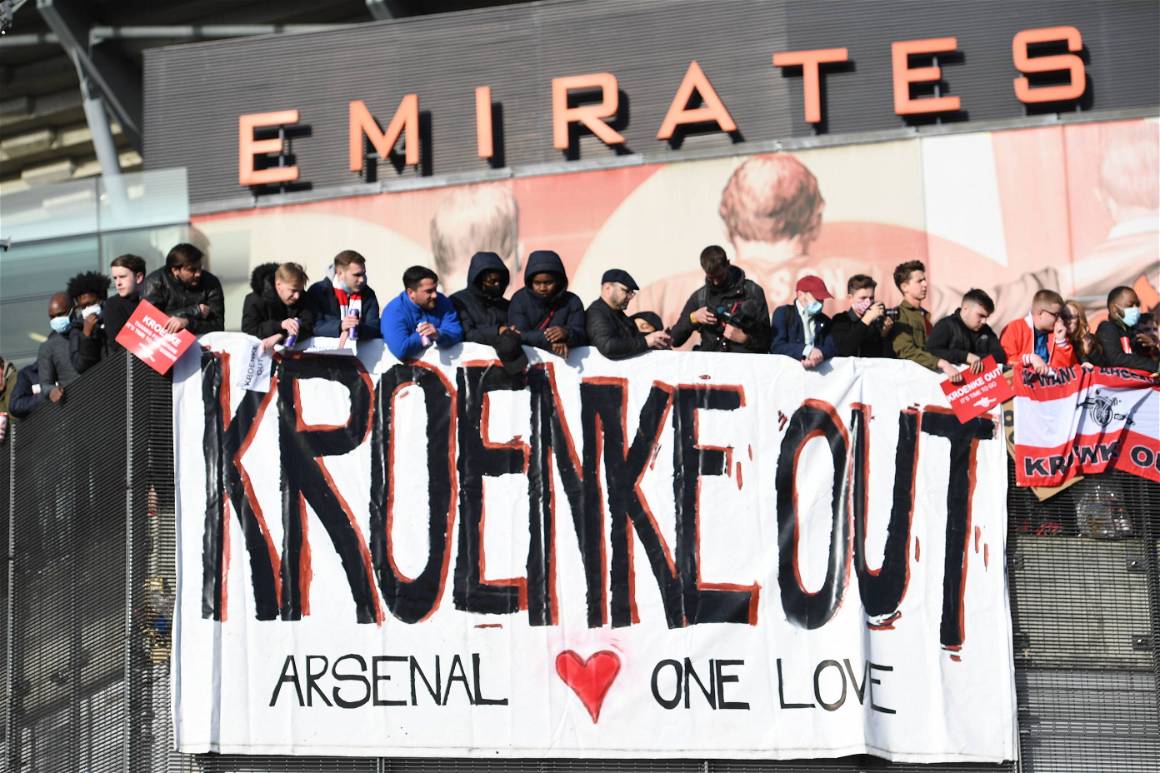

The owners of the ‘big six’ Premier League clubs were vilified for their actions, and wounds were opened that may never be healed. Whilst Liverpool’s owners FSG, and Arsenal’s bank-roller Stan Kroenke issued more formal apologies, Chelsea, Tottenham Hotspur, Manchester City and Manchester United were a little more withdrawn in their statements.

Fans protested in outrage at the Emirates and Stamford Bridge, and Old Trafford was effectively broken into by enraged Manchester United supporters forcing the postponement of their historic derby match with Liverpool. An illustration of the rebellion against the status quo was almost alarming but in a good way.

Football fans proved the strength that unity brings. In a world where so many often feel so silenced, football’s breakthrough, as a game of the people, against the often seemingly insurmountable grip that a select few have on both the game and society, made a statement. A big statement.

But where does football go from here?

It is difficult to ‘punish’ the owners of the six Super League clubs without simultaneously punishing players, staff and fans. Points deductions and similar league impacting measures also impact those who were far from involved.

UEFA have suggested that a portion of European competition revenues will be withdrawn from all six English clubs as well as AC and Inter Milan, whilst Real Madrid, Barcelona and Juventus have recently entered a legal battle in the European Courts of Justice with UEFA.

To what extent these clubs will truly be taught a lesson is unknown; however, there are clear takeaways from the Super League debacle in terms of the role of the fan in the modern-day game. Firstly, it is apparent that fan culture in different European nations naturally takes different forms. For example, in England and Germany, ‘away fan culture’ is strong, more so in the former than the latter and most definitely stronger in other European nations.

Whilst the response to the Super League has been uniformly negative across Europe, Real Madrid and Barcelona fans arguably didn’t collectively voice as much opposition. The same can be said of Italy – the backlash was markedly less severe.

As such, it’s important to recognize the different attitudes towards the Super League, no matter how terrible an idea it is to most. Not necessarily because fans should sympathize with the cause, but because we must understand that there is no quick fix across the game worldwide. This trend can be seen in life more generally – especially in politics.

Take the EU, for instance. Upon Britain’s exit from the European Union, one issue that was cited by Brexiteers and Eurosceptics alike was a question over, ideologically, how so many different countries with such unique cultures were meant to function in a single political body without failing to serve the priorities of different demographics.

As such, can we safely say that proposals such as the German 50+1 ownership model would solve the ‘money problem’ in English football at least?

In theory, Germany’s unique club ownership model would be good for every football club in the world. But, as we’ve said, this is in theory.

German football clubs are very much viewed as just that – clubs. Communities of people that, as key stakeholders, have a say in the running of the football club. The underpinning reason for such an outlook is that, as explained by Borussia Dortmund CEO Hans-Joachim Watzke in 2016, ‘The German spectator traditionally has close ties with his club…And if he gets the feeling that he’s no longer regarded as a fan but instead as a customer, we’ll have a problem.’

But what actually is the 50+1 model in German football?

Until 1998, private ownership of German football clubs was actually prohibited. When the 50+1 rule was introduced, commercial investors were only allowed to buy up to a 49% stake in the club. This means that a supporter’s trust, in which any fan should theoretically be able to become a member, owns the majority of the club, and therefore, no decisions should be able to be taken in the name of making a profit rather than for the benefit of the fans and the sport.

At Bayern Munich, ‘FC Bayern Munich’ own 75% of the club. Audi, Allianz and Adidas own the remaining 25% (8.33% each). But could this work at clubs such as Manchester United, Liverpool or Arsenal?

In theory, yes. But Premier League football, at least, would have to undergo a financial revolution.

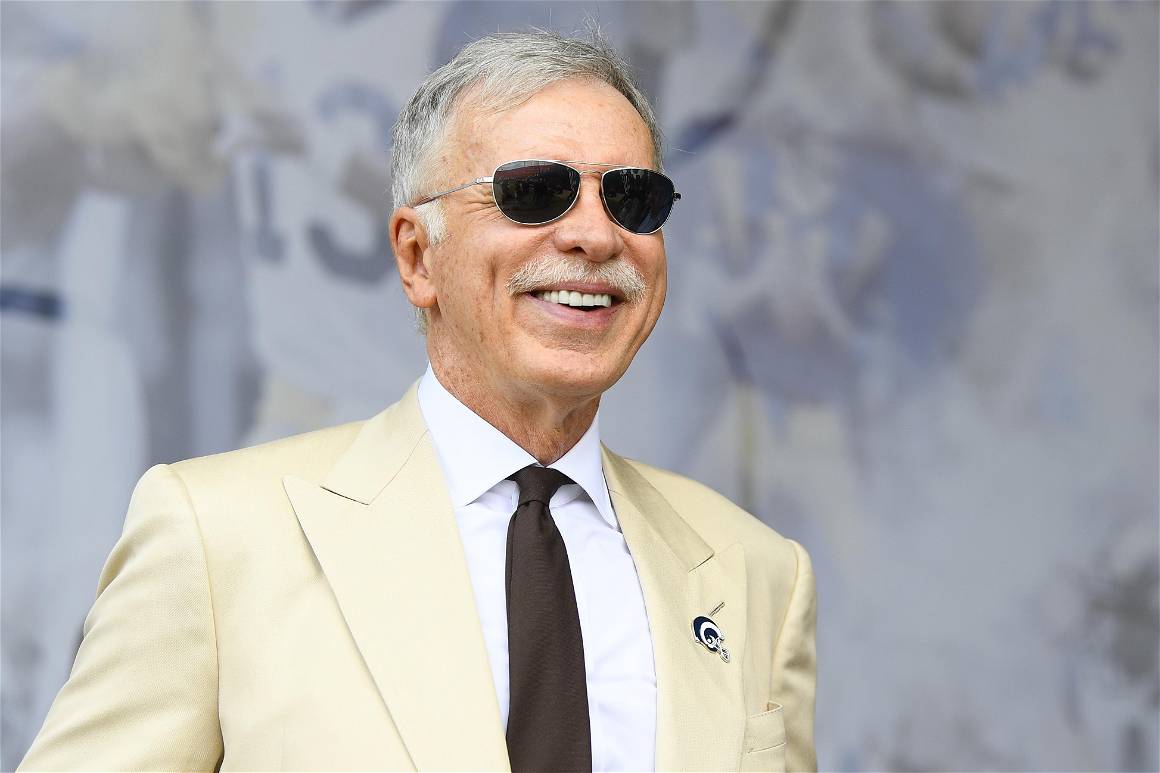

The FA or Premier League would undoubtedly have to compensate club owners whose shares were diminished. Take Stan Kroenke (Arsenal), for example. Kroenke owns more than 90% of Arsenal’s shares, and the club itself is valued at around $2bn, meaning that the authorities would likely be paying billions to a number of clubs in order to reduce their holdings.

Similarly, it has become blatantly obvious that owners such as Kroenke are in the game purely for the money. Why would they stick around if the returns weren’t as lucrative? One of the criticisms of the 50+1 model is that it deters investment from owners as they can’t make as impressive a return as if they’d invested in a Premier League club, for example.

It’s important to note that the 50+1 model doesn’t necessarily limit the amount of money that can come into a club. After all, Bayern Munich were still ranked third in the Deloitte Football Money League paper for 2020. The deal that Audi have with Bayern is rumored to be worth around $55m/year since it was renewed last January, after all, and this deal wouldn’t necessarily be struck with a smaller Bundesliga club such as Werder Bremen, respectfully.

What is does mean, however, is that the investment of clubs is always linked to performance, and performance is dictated by quality of coaching, academies, and nuanced transfer business. Clubs have to grow organically to achieve sponsorship deals to then make them richer, maintaining fan control due to the 50+1 model.

So for better or for worse, the level of competitiveness in German football will be slow to evolve.

Finally, there are plenty of English football clubs that don’t have a problem with their owners.

Leicester City’s rise over the last five years or so has included meteoric feats such as winning the Premier League in 2016 and the FA Cup only this month. But Leicester have grown in a sustainable manner, not spending beyond their means and not manipulating football fans for money.

The passing of the late Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha in 2018 was tragic beyond measure, but in some ways, it further strengthened the relationship between fans and owners. Leicester City fans are not ‘powerful’ in the same way that fans are in German football, but there is mutual trust and respect between them and the club’s board.

Leicester’s owners are rich, but they don’t abuse their money for the sake of profit. 100% of the club’s shares are owned by the Srivaddhanaprabha family, and never have they done anything to warrant a diminishment of status at the club. The same could apply to teams such as Aston Villa.

Football fans generally are not particularly powerful entities in terms of their financial or decision-making power in football clubs. However, if the Super League events and the subsequent discussion around club ownership has taught us anything, it’s that the voice of the true masses are difficult to silence.

What comes of this – or what should come of this – is yet to be decided by the European game. But we should be careful about how we go about repairing the tumultuous relationship between wealth, greed and the greater good in football. After all, the market has changed, and revolution is never a good thing.

Sam Hudspith is a freelance sports/sports business content writer, copywriter, and EFL and Premier League accredited journalist. You can visit his Muck Rack page for more information. He also runs www.thegoalkeepingblog.com – a site centered on the misunderstood men between the sticks. You can find him on Twitter @samhudspith, probably talking about Reading FC or politics.