Politics and sport are two entities that most of us would rather keep separate. People don’t tend to go to cricket, rugby, football or even the Olympics intending to engage in heated debate surrounding government policy. Quite the contrary: sport serves as a distraction from the seemingly endless drone of current affairs – none of which ever seems to be particularly positive.

Oil, Afghanistan and Jimmy Carter: Remembering Moscow 1980.

But, in their nature, politics and sport often cross paths – and no more so than they have done in the previous eighteen months.

Gaining the attention of the masses (and the money of the media), sport, in various forms, can act as a vector for social change. Given the influence that events, clubs and sportsmen themselves hold over society in general, sporting events can prove the ideal media for making a statement, whatever that statement may be.

And no sporting stage has portrayed the power of political protest more than the Olympics.

This is somewhat ironic, given that the IOC, much like a number of world sporting bodies, always aim to present themselves as politically neutral. Whilst the governing body itself doesn’t side with any political entity or ideology, the games themselves, throughout history, can hardly have been seen to be neutral. It’s not petty party politics that infiltrate the Olympics, but rather valiant causes in the interests of mankind.

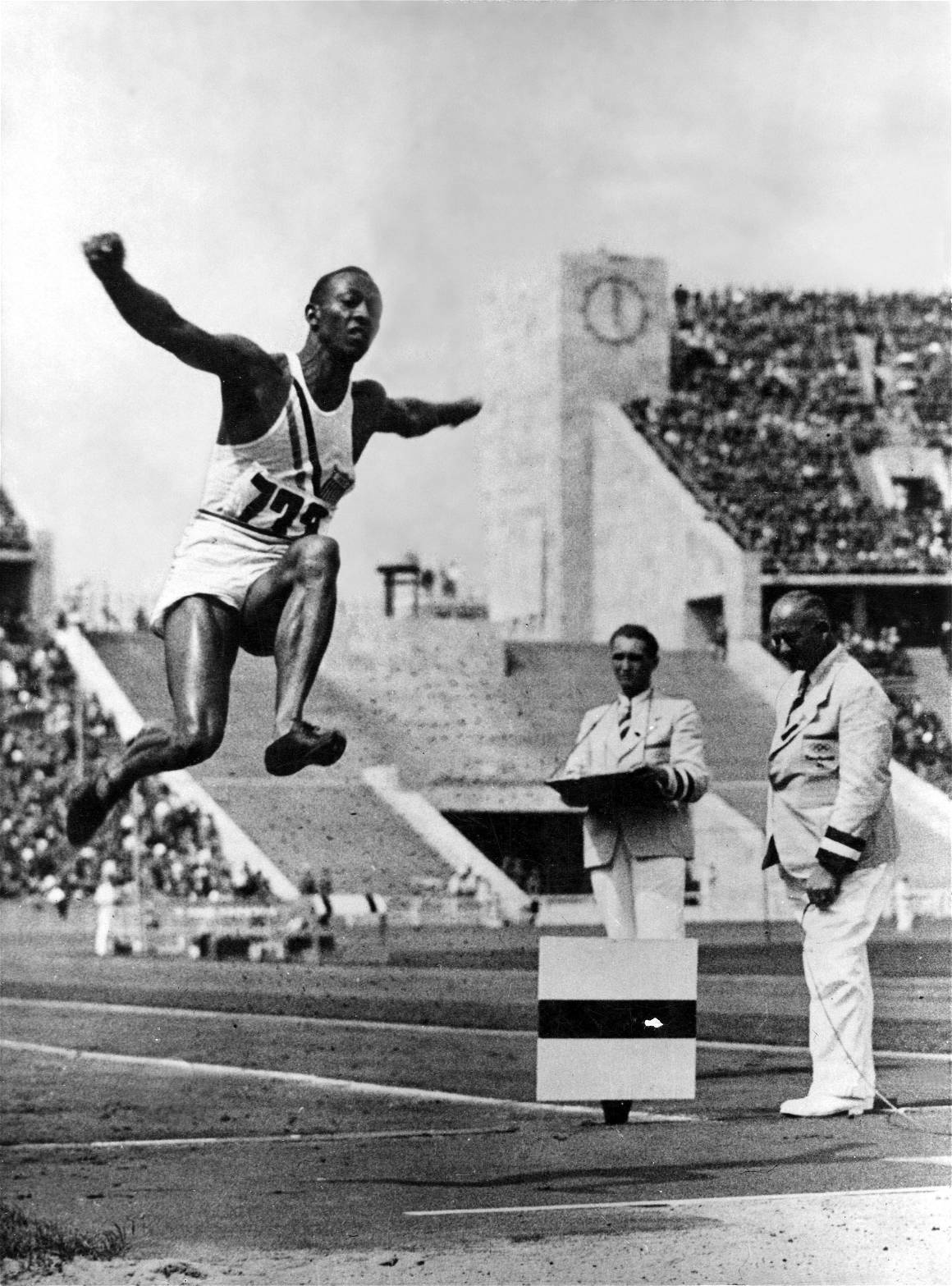

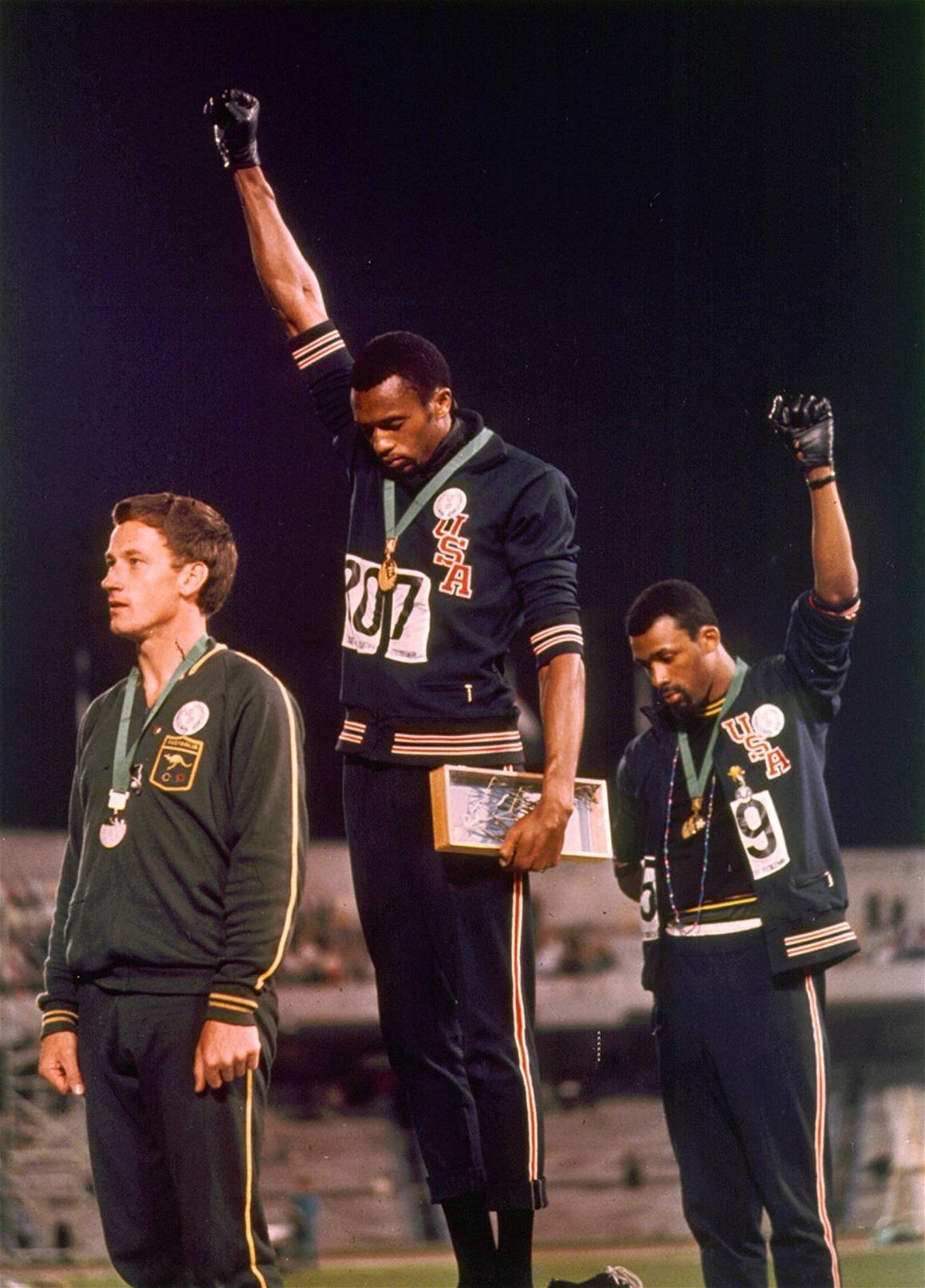

Just think of Jesse Owens in Berlin in ‘36. Smith, Carlos and the Black Power salute in Mexico in ’68, or Arash Miresemaeili at Athens in 2004. For undeniably legitimate causes, they all brought politics into sport, and are part of a group of athletes and nations who have used the platform of the gains to promote and advance their beliefs.

When athletes travel to the games, they come to live in harmony, under the Olympic spirit that promotes peace and friendship between all.

Perhaps the most recognisable symbol of such spirit is the Olympic flag, which interlinks the five continents – an iconic metaphor for the togetherness the world is too often lacking, bringing athletes together as members of one race – the human race. The Olympic Truce is another example – renewed in 1992 to promote humanitarian aims through the games.

Originating in Ancient Greece nearly 3000 years ago, the original purpose of the truce was to ensure a safe passage for athletes travelling to the game in what were volatile, war torn times across the ancient continent. As the world entered a new socio-political era in the 1990s (with the Cold War coming to an end, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union all occurring towards the end of the previous decade and into the nineties), the Olympic committee took steps to promote the creation of a more cooperative, peaceful planet by renewing the truce and using sport as the vector to enact such change.

South Korea and North Korea entering the 2000 Sydney Olympics side by side, becoming the first divided country in Olympic history to do this, was a poignant example of the power of sport. But, in times gone by, such solidarity has been a rarity. Defiance, yes, but solidarity, no.

Let’s go back to the 1970s on the other side of the pond: 1970s America – January 20th, 1970, to be precise.

*

Richard Nixon has been in the White House for exactly one year. His first 12 months at the reins of the western superpower have seen the beginning of the end of the United States’ involvement in Vietnam, a subsequent rejection of Viet Cong troop removal from South Vietnam by Ho Chi Minh, and a trip to the moon.

Nixon, labelled by history as a President at the mercy of both a worsening economy and his own intense paranoia, has had a positive first year in office. In February 1970, his approval rating sits at around 64%. But the worst is to come for Nixon.

1971 sees the leak of the Pentagon Papers, the Kent State Shootings of 1972 add heaps of oxygen to the counterculture fire, inflation begins to slyly rise, and an impeachment, following the Watergate scandal, is nigh. A visit to the USSR in that year is something of a landmark in the state of play of the Cold War, but little more than that. Munich, ’72.

1974 sees Nixon’s resignation and the taking of the top job by Vice President Gerald Ford. A pardon of the former president the same year marks Ford down in many American households. The Saudi Oil embargo hikes fuel prices by around 300%. The Fall of Saigon in 1975 brings the 20-year-plus conflict in South Asia to an end. Unemployment rises to 8.1% – the highest since 1941 – and in May of ’75, peaks at 9.2%.

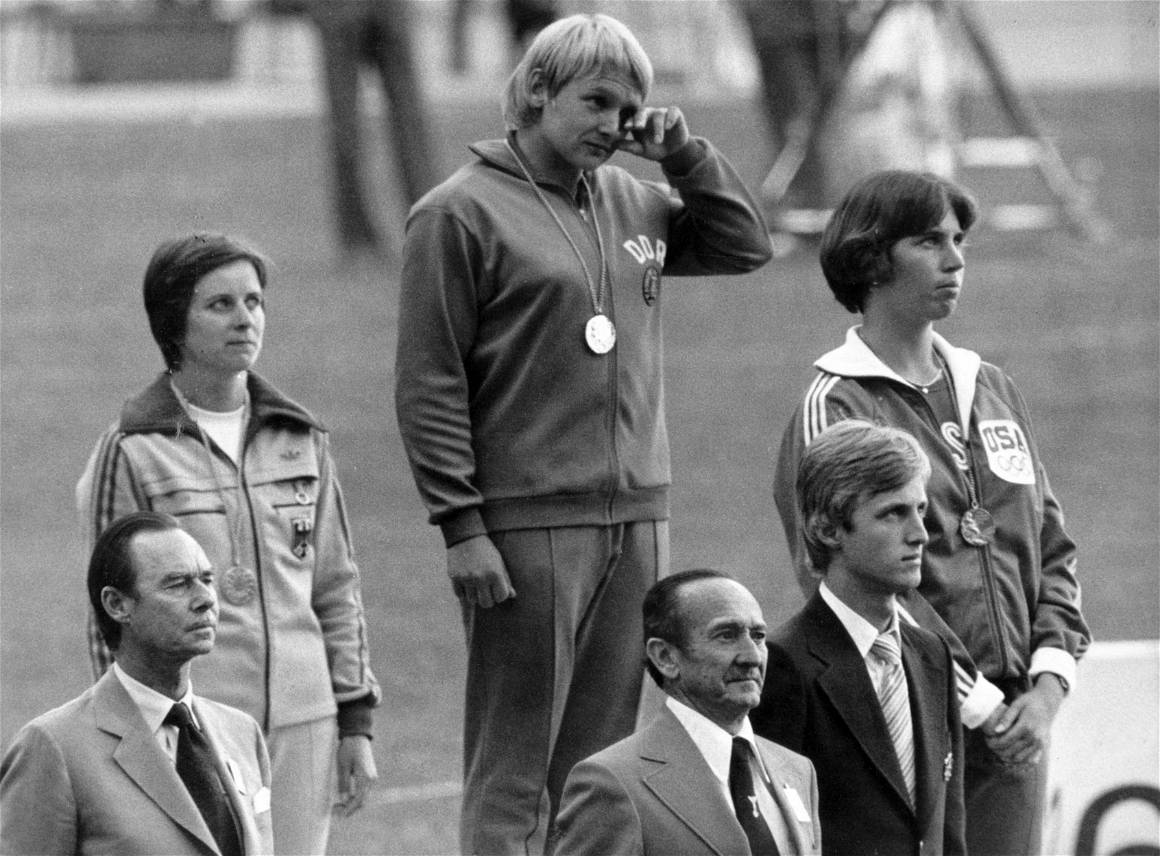

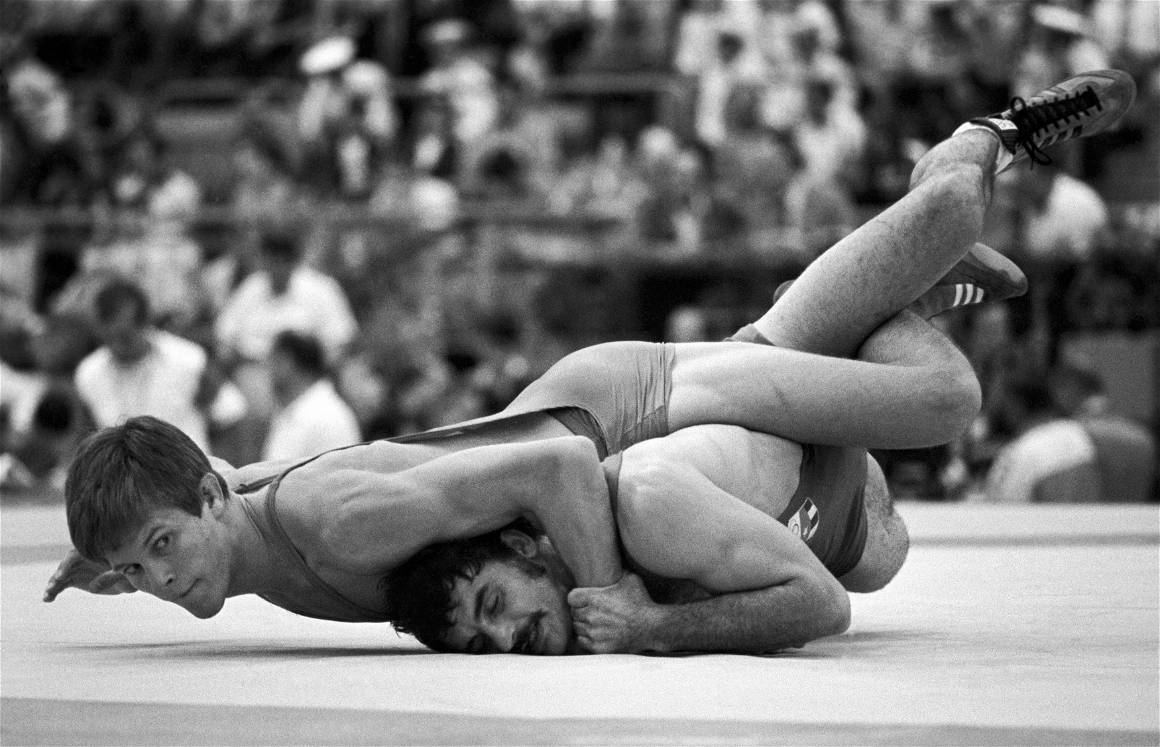

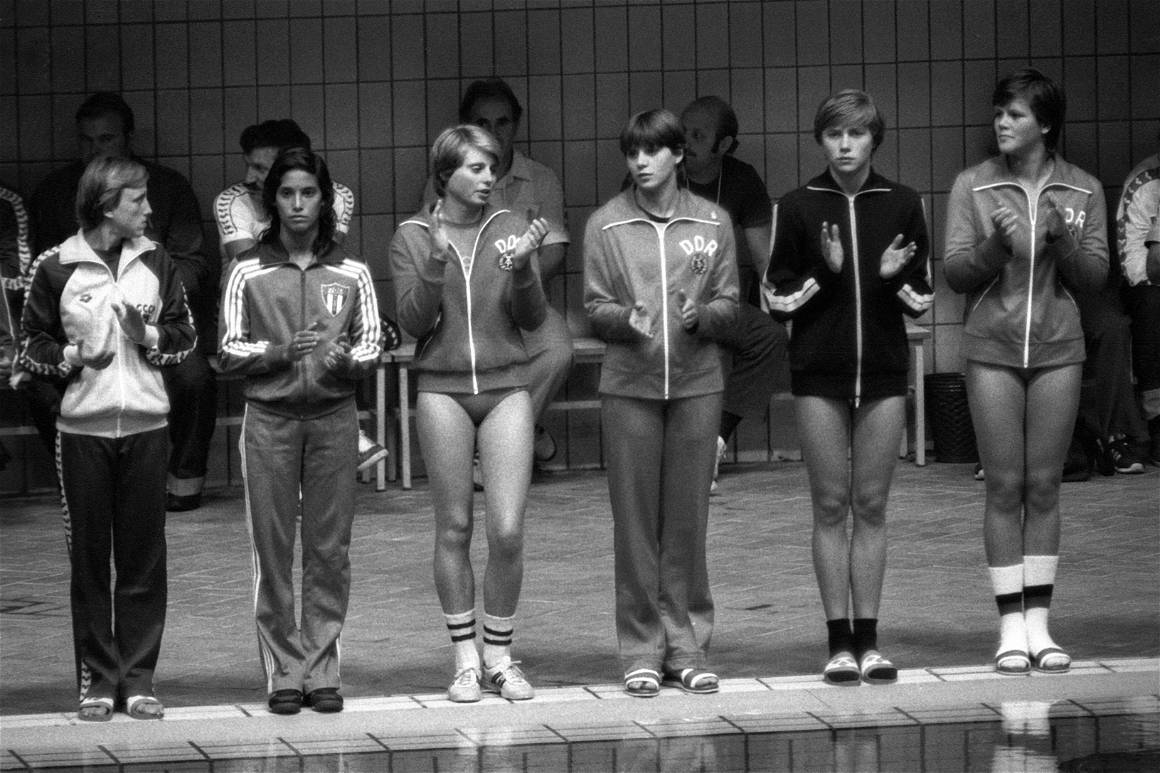

In ’76, Chairman Mao dies, creating more instability in China and the Eastern Bloc. East and West German athletes continue an ‘encouraged’ doping culture at Montreal, ‘76.

The Democrats take the White House in 1977 with Jimmy Carter at the helm. An ex-potato farmer and Governor of Georgia, Carter’s presidency goes from failure to failure. His energy plan encourages sweatshirts over thermostats, big car taxes and the closure of petrol stations on Sundays. America freezes as inflation soars into double figures by 1979, and the Iran hostage crisis begins.

In 1979, something had to give, and it would turn out to be Carter in 1980. But Jim the Peanut Farmer was to make one last valiant stand, and it came in the form of sport.

Christmas 1979. Joy and Peace on earth. Except there isn’t. Soviet tanks rumble through the Middle Eastern desert and into Afghanistan.

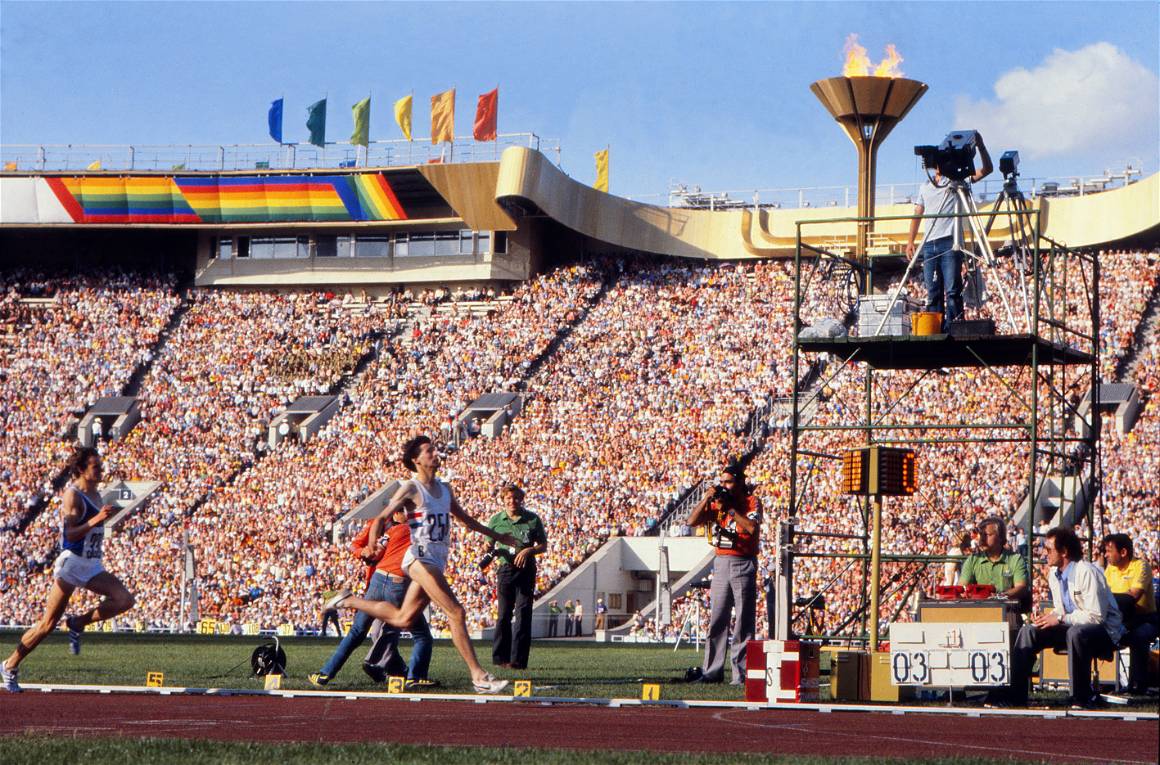

And then there’s Moscow 1980.

*

March 21st, 1980. Bill Monroe interviews President Carter on NBC News, questioning him about the Soviet’s actions.

In his rather dry voice, Carter made his position staunchly clear on NBC news.

“Neither I nor the American people would support the sending of an American team to Moscow with Soviet invasion troops in Afghanistan. I’ve sent a message today to the United States Olympic Committee spelling out my own position that unless the Soviets withdraw their troops within a month from Afghanistan that the Olympic Games be moved from Moscow to alternate site or multiple sites or postponed or cancelled”.

The USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan supported the Afghan government who were fighting a guerrilla war against a host of insurgent groups covertly supported by several western nations, including the United States and the United Kingdom. A year earlier, in 1978, the Afghan government had been overthrown in a coup d’état by the communist party of Afghanistan.

Their rule was deeply unpopular, deeply undemocratic and saw ruthless execution and oppression of the people of Afghanistan. Needless to say, Brezhnev backing the new government went down like a sack of bricks amongst the Western bloc.

In fact, Carter even suggested the creation of a permanent, neutral Olympic site – namely Greece – to replace the games travelling around the world each Olympiad.

Carter reignited his argument at his 1980 State of the Union address. Polls suggested that the American public were on board with the boycott, with around 55% supporting it. However, the confirmation of the decision was deeply unpopular with the athletes themselves. The US Olympic Committee (USOC) begrudgingly agreed to the boycott on April 12th. It was only after intense lobbying that this was achieved.

Julian Roosevelt, an American member of the International Olympic Committee, famously said that ‘I’m as patriotic as the next guy, but the patriotic thing to do is for us to send a team over there and whip their ass’. This sentiment was echoed by other athletes and those not in favour of the boycott.

In February of 1980, the ‘Miracle on Ice’ had played out in New York, pitting the Soviets against the States in a David vs Goliath fixture. The United States won 4-3, and many sourced this as an example of the humbling nature of sporting achievement that the Moscow games could bring, should the USA upset the apple cart.

The US government did not have any viable legal measures to prevent the USOC sending athletes, however, and other Western nations were sceptical about joining the boycott.

West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt was perhaps more bothered by America’s approach than by the boycott in principal. Nicholas Sarantakes, in his book ‘Dropping the Torch: Jimmy Carter, the Olympic Boycott, and the Cold War’, said Schmidt held the view that ‘the American attitude that the allies “should simply do as they are told” was unacceptable’.

Other nations were not particularly impressed with President Carter’s diplomatic attempts either. Despite going down in history as the President whose intentions were simply ‘too nice’, Carter’s decision to send Mohamad Ali to Tanzania, Nigeria and Senegal to persuade them to join the boycott was ultimately successful. However, Ali’s reception was noted to be somewhat frosty – many politicians in the aforementioned countries felt it was disrespectful to send Ali rather than Carter visiting himself.

Nonetheless, Tanzania, Nigeria and Senegal, as well as Kenya, were persuaded to join the boycott. Japan and West Germany did (eventually) join the boycott, along with Norway, Canada and 56 other nations.

In America, the overwhelming feeling from the Olympians themselves was that they were being used as pawns in a political game they wanted no part in. Carter did technically have legal measures available, but not viable ones. He could theoretically confiscate the athletes’ passports, but Carter’s public support couldn’t really dwindle any further and doing that would have (tongue in cheek) probably taken him into negative figures.

Great Britain and Australia showed support for the boycott, but neither participated albeit sending reduced-sized teams to the games. Sebastian Coe, now Lord Coe and President of World Athletics, was fervently unsupportive of the boycott and famously left Moscow with a gold medal for the 1500 meters.

Historians are divided over whether Carter’s actions can be seen to be successful. But it wasn’t the first time that politics encroached into sport – and certainly won’t be the last.

2020 and 2021 have been years of turmoil in so many ways. Protests against racism, police brutality, lockdowns and government action have polarised the populations of many a country. The IOC are keen to keep Tokyo 2021 separate from any form of demonstration.

At Tokyo 2021, various forms of Black Lives Matter protests were said to be under plan. However, the IOC have held steady with the controversial ‘Rule 50’, banning any form of political protest at the Olympic Games.

It does seem that those inclined to make a statement are in the minority, however. Earlier this year, the IOC surveyed 3500 Olympic athletes representing 185 different nations across all 41 sports. Of those 3500, 67% said they wanted to keep the Olympic podium free from protests, and 70% wanted to avoid on-field demonstrations.

President Thomas Bach said in January 2020 that ‘Our political neutrality is undermined whenever organizations or individuals attempt to use the Olympic Games as a stage for their own agendas, as legitimate as they may be’.

It remains to be seen if such rules will be adhered to. In this day and age, that’s arguably unlikely.

Sam Hudspith is a freelance sports/sports business content writer, copywriter, and EFL and Premier League accredited journalist. You can visit his Muck Rack page for more information. He also runs www.thegoalkeepingblog.com – a site centered on the misunderstood men between the sticks. You can find him on Twitter @samhudspith, probably talking about Reading FC or politics.