The Game columnist Andy Murray explores the staggering disparity in prize money in women’s football and how it could affect the game’s exponential rise.

English football’s secret: the scandalous gender pay gap

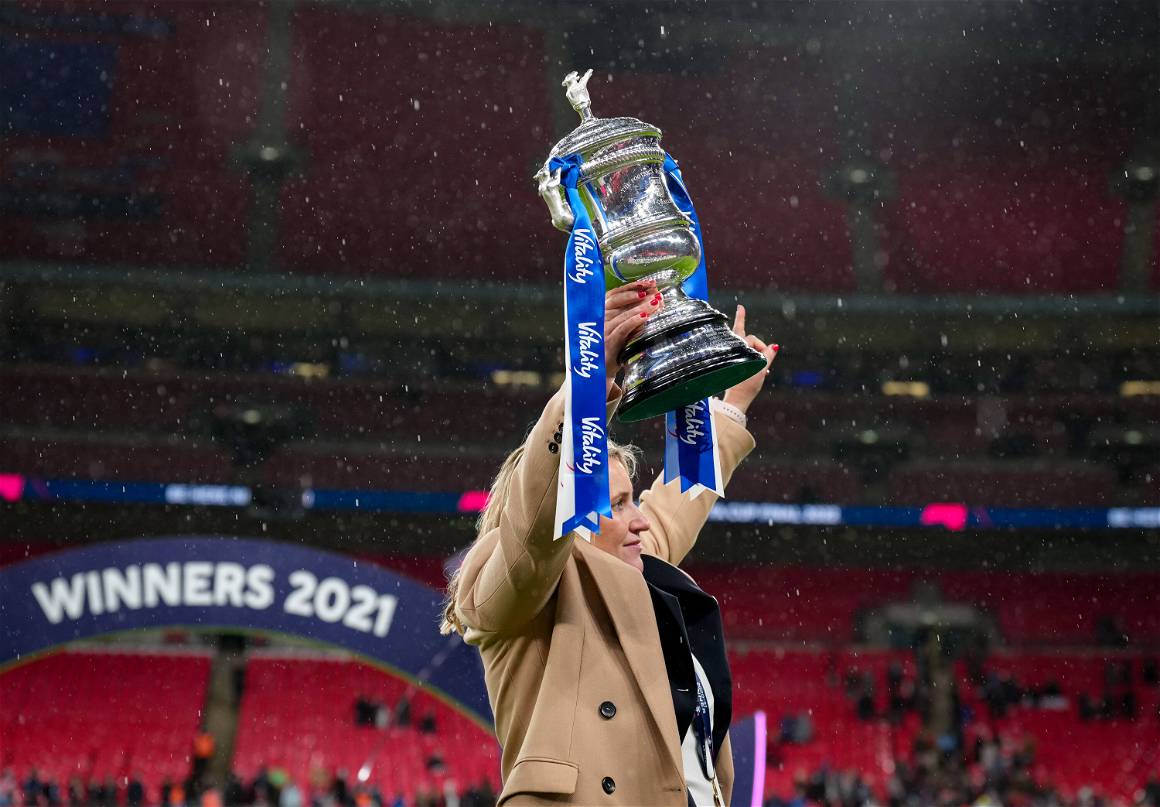

The atmosphere was like no Women’s FA Cup final before it. On Sunday December 5, more than 41,000 excited, expectant fans thronged Wembley Way to watch Chelsea and Arsenal, the WSL champions versus the current league leaders, do battle in the 2021 showpiece. Here was a London derby between England’s two biggest teams in the sport’s most important one-off domestic fixture. And, unlike the barrier-crushing, cocaine-fueled mob which marred the men’s Euro 2020 final between England and Italy in July at the same venue, there was not even the merest trace of trouble.

Families were everywhere. Some wore Chelsea blue, others Arsenal red and a not inconsiderable number were just desperate to experience the spectacle of the elite of the elite meeting in a final as a Sam Kerr brace followed Fran Kirby’s third-minute opener to secure a comprehensive 3-0 Chelsea win. If you needed any further proof that women’s football’s star was very much in the ascendant, the 50th Women’s FA Cup’s final provided it.

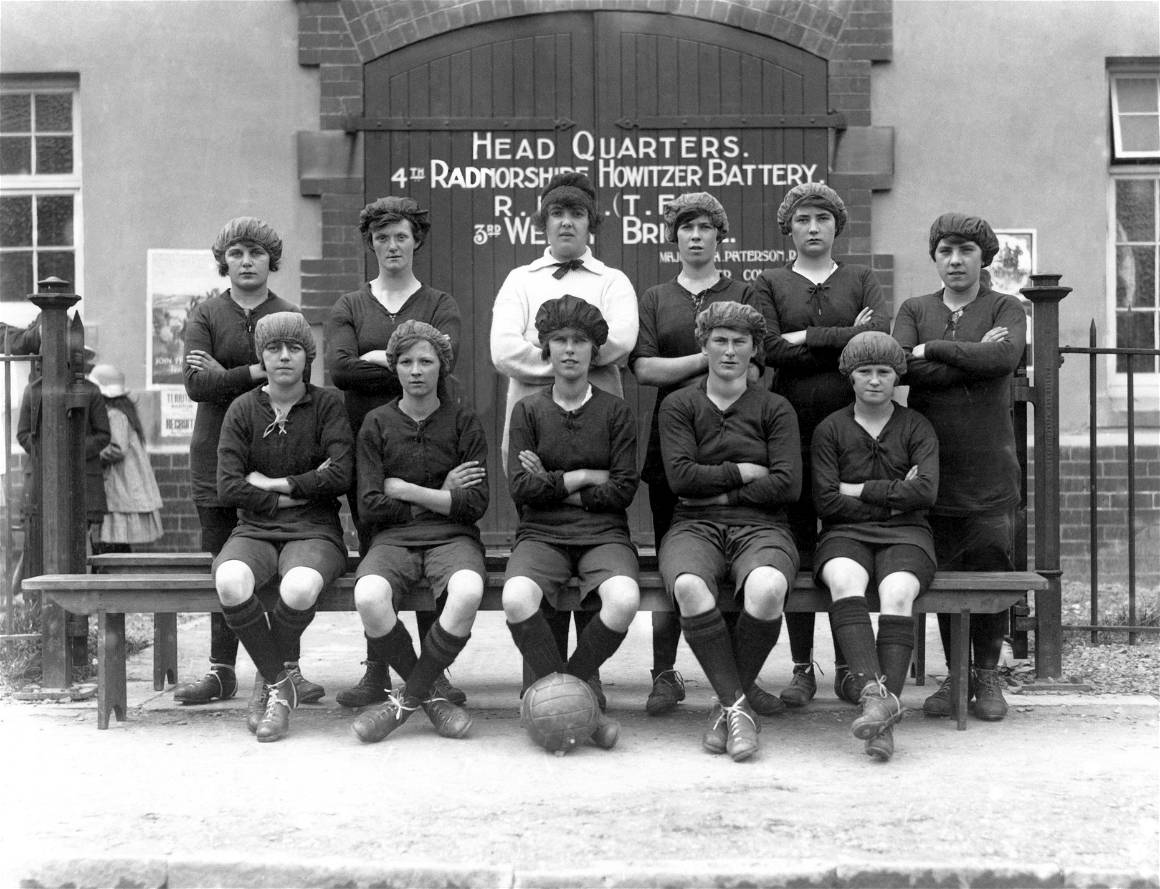

Delayed since early-summer because of the pandemic, the game marked another anniversary, one which the FA were less keen to publicise. One hundred years earlier, to the day, the game’s governing body banned women from playing at its Football League grounds, reasoning the sport to be “quite unsuitable for females”, presumably for fear that their ovaries might explode if they were to kick around a spherical object for 90 minutes.

Think that’s a joke? Further investigation of the medical ‘experts’ the FA consulted at the time includes further detail. “Kicking is too jerky a movement for women,” it said. “The frame of a woman is more rounded than a man’s, her movements should be more rounded and less angular.”

Many believe the FA saw women’s football as an active threat to the men’s game – 53,000 came through the Goodison Park turnstile on Boxing Day 1920 to watch the pre-eminent Dick, Kerrs Ladies in a friendly – and sought to re-establish some authority. The ban lasted for nearly 50 years and set the sport back far longer in terms of coaching, visibility and money. Even when the ban was lifted, the FA didn’t take supreme charge of the game until 1993, starving it yet more of funding and basic resources. Dinosaurs who criticise the quality or relevance women’s football – a former editor of mine included – are either wilfully ignorant of its history or wilfully disingenuous in patronising praise about everything “except the goalkeepers are rubbish”. The quality is excellent, and improving all the time. Deal with it.

The 2021 final brought back into view the scandalous disparity in prize money. Chelsea, who have benefited from more investment from their enlightened men’s team than most, won just £25,000 for lifting the trophy, compared with £1.8million for men’s winners Leicester. Even winners of the men’s 2020/21 FA Vase – a tournament for non-league teams whose players are semi-professional or even amateur – won over £10,000 more in prize money than Chelsea Women. Compare the 6,000 fans in attendance that day at Wembley with the 41,000 for the Women’s FA Cup final – plus a peak TV audience of 1.3million on BBC Two, which dwarfed the FA Vase’s subscription-based model – and the figures become ever-more impossible for administrators to justify.

“Why is it we don’t get more prize money? We need more being invested so it can trickle all the way down,” said Chelsea boss Emma Hayes, a vocal critic of women’s football lack of visibility, before the final. “We need more prize money for everyone, not just the winning team. I don’t think the prize money is anywhere near where it needs to be, nor where the men’s game is.”

Over the weekend of December 11 and 12, the 2021/22 Women’s FA Cup reached the third-round stage. Teams who progressed stood to earn a paltry £1,250 – the equivalent stage in the men’s tournament is £82,000 in winnings. The total prize pot is £309,000 compared with £15.9million.

Fan-owned second-tier side Lewes – the first club in England to provide equal pay for its men’s and women’s teams – highlighted the costs clubs incur just to fulfil these fixtures by tweeting “this Sunday EVERY away team in the women’s FA Cup will LOSE. Guaranteed.”

Clapton Community FC became the first seventh-tier side to reach the third round but so derisory was the prize money, they had to set up a crowdfund page – having been drawn away in each previous round, beating fourth-tier Hounslow en route – to pay for their travel and accommodation for the 230-mile trip to Plymouth.

Is it any wonder critics of women’s football hammer its strength in depth when the playing field is anything but level and more closely resembles Mount Everest? Below the third tier, trickle-down economics are more important than anything to provide the grassroots infrastructure that can help women’s football thrive. The success of the WSL and its new £24m TV rights deal with Sky Sports and the BBC is a start, but only if the money reaches the clubs who will be at the forefront in providing the platform for the next generation to get their football fix.

“We’re not asking for equal pay. That’s a myth,” Clapton captain Alice Nutman told The Guardian before their eventual defeat at Plymouth last weekend. “We’re asking for investment in grassroots and we’re asking for spaces in which women and non-binary people are able to play football, which currently do not exist. It means that you’re not living hand to mouth each month. We struggle to pay for our training pitch. That’s the reality of playing grassroots football in this country as a woman.”

In calling out the football’s gender pay gap, Clapton, Lewes and Emma Hayes are demanding investment at a proportionally higher rate to redress the balance, at a time when broadcasting deals, sponsorship and prize money in the men’s game continue to swell. The US Women’s National Team generates more revenue than the men’s team because it began from broadly the same base, on an equal footing. That 50-year ban makes that impossible in England, so more must be done to redress the balance.

Now is the time for administrators to act – or be shamed into acting – if women’s football is to avoid another 50 years in the wilderness, right at the point when it seems set to make it to the mainstream.

Andy Murray is a sports writer and columnist for The Game. Check out some of his other articles with us that feature both in our mag and in our first zine issue FANsided.