On the surface, Liverpool have been a perfectly run super-club ever since Jurgen Klopp charmed fans and media at his unveiling in October 2015. They are the example to all the rest. The ideal manager was appointed and backed, while Michael Edwards – now sporting director – was already behind the scenes working on a masterful recruitment strategy.

Why Jurgen Klopp Cannot Keep Performing ‘Mission: Impossible’ At Liverpool

By Alex Reid: The Fenway Sports Group (FSG) have not invested the eye-watering sums spent – and sometimes wasted – at Manchester City, Manchester United, Paris Saint-Germain or Barcelona. But Liverpool have made progress every year. From struggling in eighth place in the Premier League when Jurgen Klopp took over to Europa League finalists, Champions League finalists, then Champions League winners; all while surging up the league table to 2020’s cathartic title victory.

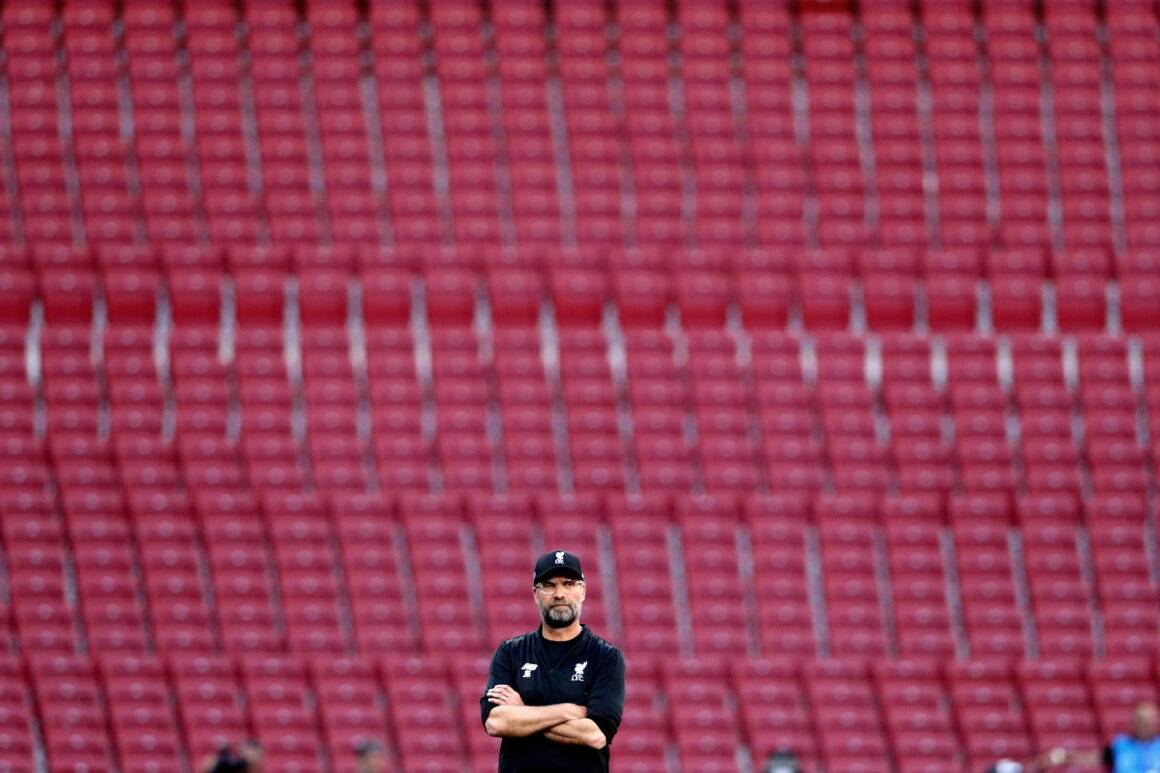

Photo: IMAGO. Jan Huebner

The quality of the playing staff has been transformed. The last five years have seen the likes of Simon Mignolet, Mamadou Sakho, Nathaniel Clyne and Adam Lallana – all starters in Klopp’s first game against Tottenham – replaced by Alisson, Virgil van Dijk, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Mohamad Salah.

But rather than “five years”, we should alter to “three-and-a-half years”. Because for the last two summers, Liverpool have been curiously conservative on the transfer front. Eyebrows were raised last summer when Liverpool spent a total of £1.3 million (Takumi Minamino, bought in January 2020 for £7.25 million, was the only major signing of the 2019/20 season).

Photo: IMAGO. GEPA pictures

Even this summer, while Liverpool have been praised for their cunning recruitment, it has all been done on the budget of a mid-table Premier League club rather than one of Europe’s elite. Kostas Tsimikas, Thiago Alcantara and Diogo Jota were added to the squad for less than £30 million in net spend.

Of course, the Premier League is guilty of fetishing transfers and their fees; of believing that only spending money can solve a problem. But there is a reason for that. The cold, harsh lesson of England’s top flight is that the heftiest spenders always come out on top in the end.

Manchester United used their financial and marketing muscle to dominate early on (interrupted by Blackburn’s entirely money-powered title win). Eventually Chelsea rose in power under Roman Abramovich, United bit back, before Manchester City gradually assumed dominance thanks to the wealth of Sheikh Mansour.

There are one-season anomalies: Arsenal, while hardly paupers, outperformed in the first half of Arsene Wenger’s reign. Leicester had the miracle of all miracle seasons. But even Arsenal failed to defend a Premier League title win.

The unromantic, inconvenient Premier League truth is that cash rules and if you fail to even keep close to your rivals’ spending power, even the greatest of managers (such as Klopp) or the most savvy of transfer strategists (like Edwards) will eventually come unstuck. And do not let Liverpool’s impressive blend of youth talent and bargain talent fool you: they are being outspent.

The failure to sign Timo Werner, a player Klopp clearly wanted, is a huge red flag. A 24-year-old Germany international striker available for the extremely reasonable fee of €50 million and who seemed ready to join the club earlier in the year. Yet this season he plays in Chelsea’s blue.

Photo: IMAGO. PA Images

Klopp put a brave face on Werner not arriving, telling Sky Germany: “All clubs are losing money. How do I discuss with the players about things like salary waivers and on the other hand buy a player for £50 to 60 million – we’d have to explain. If you want to take it seriously and run a normal business, you depend on income.”

Level-headed talk but not something that will help Liverpool on the pitch as Chelsea and both Manchester clubs all look to have recruited well over the last 18 months. Neither Manchester United nor Chelsea are currently maximising the talent in their squad, partly as both employ managers who got their jobs on the basis of their playing rather than coaching careers. But that could well change.

Some will also argue that Liverpool got to where they are not by spending big but spending smart. Financially, the club have broken even in each of the last three years. The two major signings during this period of soaring fortunes – Van Dijk (£75 million) and Alisson (£66.8 million) – were largely negated by the sale of Philippe Coutinho to Barcelona in 2018 for a fee up to £147 million.

Photo: IMAGO. Action Plus

Nonetheless, the club did invest heavily in the very best, such as that duo, when it was required. They have not done so since. And, while it may appear a ludicrous suggestion given the 18-point margin with which they won their domestic league last season, this is a squad that needs reinforcements.

It should worry Liverpool fans that many of their crucial outfield players are now in their late twenties. Salah and Sadio Mane are 28, Van Dijk and Roberto Firmino are 29 while captain Jordan Henderson is 30. Hardly ancient. But it makes Alexander-Arnold – a mere 22 – the only one of Liverpool’s core of ‘essential’ players who is almost certain to improve.

Photo: IMAGO. Colorsport

This is not to suggest the wheels will suddenly come off Liverpool this season because their key performers are closer to 35 than 20. And Liverpool do have a crop of talented youngsters, headed by 19-year-old Curtis Jones. But they are not all first-team ready. And the lifespan of a really successful club side in the modern era is generally about two-to-three years, before a major refresh is required. Even Pep Guardiola’s game-altering Barcelona only dominated for three seasons before things slid in their fourth season.

Photo: IMAGO. PanoramiC

With Liverpool achieving a mind-boggling 196 points across two league seasons and winning the Champions League a year ago – as well as reaching the final in 2018 – they have already had their two-to-three top seasons. Now refreshment is needed, yet the club is still spending cautiously rather than eyeing the talents (such as Jadon Sancho or Erling Haaland) that could set the club up for the future.

It is bizarre because John W Henry and Tom Werner have so far proved a savvy owner and chairman combination. They are blessed to have a manager such as Klopp, naturally. A coach who relishes the opportunity to improve any footballer with the right attitude and who, unlike some of his colleagues, is not known to curl his lip and moan to the press if his club is not splashing millions in each transfer window. But even Klopp must know that, as the games pile up fast and injuries mount, the squad depth of their rivals could play a big role in the season ahead.

Photo: IMAGO. Colorsport

There are further concerns. Liverpool, more than any top team in the Premier League, rely on the crowd to feed the energy of the players on the pitch. It’s something Klopp was keen to point out when he first took over, even getting on the wrong side of fans by scolding them for leaving Anfield early. “The goal came after 82 minutes… and I saw many people leaving the stadium,” he said after a 2-1 defeat to Crystal Palace in 2015. “I turn around and saw them go. I felt pretty alone at this moment.”

The point was forcefully made: he needed the Anfield crowd to buy into his methods, to support his team to the end, as Borussia Dortmund’s supporters had done. It ruffled feathers but Klopp converted any doubters a long time ago and now the club’s raucous support is a crucial element in that mythical manager-fans-players triangle. Until now.

Photo: IMAGO. Sportimage

Of course, there is nothing that Henry, Tom Werner or anyone else at FSG can do about the impact of a global pandemic on attendances at sporting events, even as their own club suffer more than most. But plenty they could do to stop their all-conquering side from going stale.

The obvious answer to why Liverpool have not seriously outlayed in recruitment this year nor last year is financial restraints. This is a club deeply feeling the impact of Covid-19, without an entire Gulf state to fund them, without ticket income, while having to keep their current stars happy in their contracts.

Klopp took a veiled dig at Manchester City and Chelsea as the 2020/21 season began, saying: “For some clubs it seems less important how uncertain the future is. Owned by countries, owned by oligarchs, that’s the truth. We are a different kind of club.”

But this is slightly disingenuous, as John W Henry is hardly poor. His net worth has grown during his ownership of Liverpool to an estimated $2.8 billion in 2020. Some fans may begin to ask why some of that cannot be invested into the club (even in a cold, prudent light it would at least act to protect his investment and ensure Liverpool don’t get caught by the Premier League’s chasing pack).

Liverpool supporters may not like what they see when they look at the USA and the dire situation in which the FSG-owned baseball team, the Boston Red Sox, find themselves. World Series Champions in 2018, the owners infuriated fans by trading star player Mookie Betts in February – the equivalent of LFC selling Alexander-Arnold – in order to cut costs. The baseball giants struggled embarrassingly in the 2020 season, finishing bottom of their division.

It’s too simplistic to draw a direct line between FSG’s troubled ownership of the Red Sox and Liverpool. Yet the question remains: are finances really so tight at one of the world’s biggest, most successful and most marketable football clubs that they can’t afford to match Chelsea’s fee for Werner? A deal that, after the transfer of Kai Havertz, is only the second-biggest outlay the London club have made on a German international this year. It seems almost shocking that Liverpool appear, from the outside, so unwilling or unable to match the spending power of their rivals.

The beauty of football is that the proof will eventually come on the pitch. Some Liverpool fans will have breathed a sigh of relief when the October transfer deadline passed and Mane and Salah were still at the club. But is looking at a line-up that has only been slightly altered in two years – going on three – really a recipe for success for the future?

Photo: IMAGO. PA Images

FSG haven’t taken many wrong steps since their 2010 takeover, particularly since Klopp’s arrival. But the club’s relative recruitment inertia as their first-team stars head toward their 30s is in danger of undoing all of that good work.

Liverpool have climbed at a thrillingly steep rate over the past five years. Fans had better hope that, having scaled this near-impossible mountain and reached the summit, a steep descent is not staring this club and its owners in the face.

Photo: IMAGO. ULMER Pressebildagentur